Former police officer José Ribamar Silveira was nearly killed when he fell into this gully.

He got lost as he was driving home from a party one night in May 2023.

As he turned the car around, the 79-year-old reversed and accelerated backwards. It was dark, there were no warning signs or barriers around the voçoroca, and before he knew it, the car – with him inside – plunged into the vast hole.

“When the car slid, even though it was falling quickly, I thought of my youngest son,” he tells the BBC.

Baby Gael had turned four months old the day before. “I asked God to protect me so that I could raise my little son,” says Lt Silveira.

He was knocked unconscious and woke up at the bottom of the ravine three hours later. After a complicated rescue operation and months of convalescence, he can now walk without crutches.

His experience is a vivid example of the risks facing Buriticupu’s 70,000 residents.

As more gullies appear, there are fears that the city in Maranhão state, on the edge of the Amazon rainforest, could be split in two. At 350m above sea level, Buriticupu has about 30 gullies, with the largest two separated by less than 1km.

“If the authorities don’t contain this, they will meet and form a river,” says Edilea Dutra Pereira, a geologist and professor at the Federal University of Maranhão.

Gullies have been part of the Earth’s geological history for millions of years.

But Prof Pereira and other experts we spoke to said that existing gullies are expanding more rapidly and they fear new ones will open because of climate change, which can make rainfall more intense.

And in places where cities grow without the right planning and infrastructure to deal with rainwater, the risk increases.

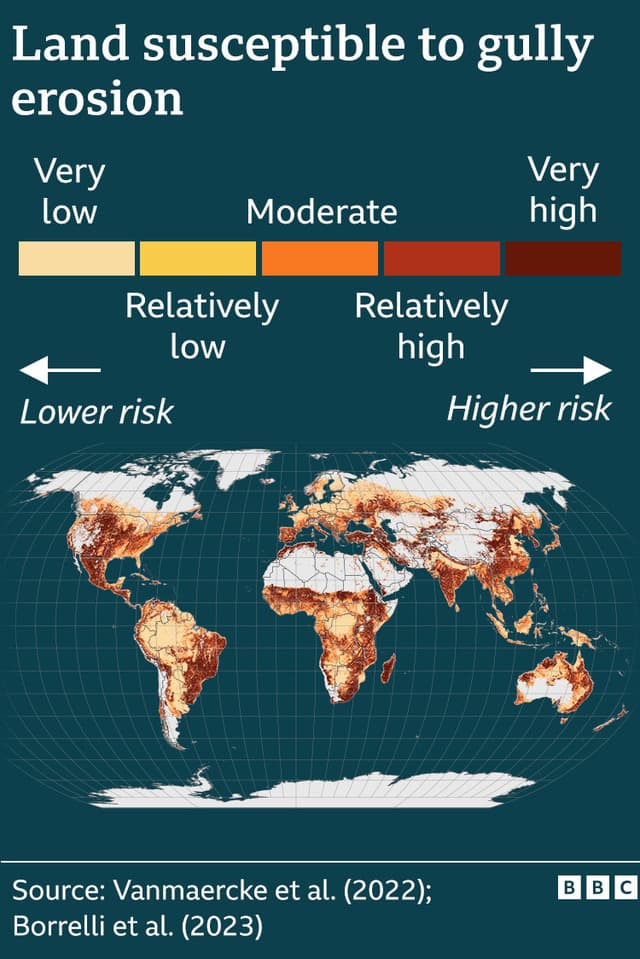

Brazil is the worst-affected country in Latin America, but Mexico, Colombia, Ecuador and Argentina also suffer from the same problem. And beyond the continent, countries in Africa, such as Angola, the Democratic Republic of Congo and Nigeria – where some gullies are more than 2km long – are also affected.

This type of erosion threatens fertile agricultural land in some parts of China, the US and Europe too.

“Too dangerous” to live here

There are no official statistics for gully-related deaths, but the authorities in Buriticupu say gullies have swallowed up at least 50 houses and some residents have had to abandon their homes, leaving neighbourhoods deserted.

Marisa Cardoso Freire’s house sits on the edge of a gully and was labelled “high risk” by the local Civil Defence Force in May 2023.

Along with 100 other families, she had to leave her home and move to another part of Buriticupu.

City Hall promised to cover the rent of new homes for displaced people, but Marisa says the municipality has not paid rent on time and she has been threatened with eviction.

When we contacted Buriticupu City Hall to ask what was happening, it failed to respond.

At Marisa’s old home, two of the family’s dogs fell into the canyon and died.

Then one day she was trying to get her 10-year-old son Enzo, who is autistic, to come back into the house and she raised her voice.

Enzo got angry and ran to the edge of the gully. “If you shout at me again, I’ll throw myself in the hole,” he threatened.

“That’s when I told my husband that we couldn’t stay here any longer, it’s too dangerous”

She will probably never be able to live in the home she built.

“When I left, my heart hurt because it’s something we fought so hard to achieve.”

How did it reach this point?

Deforestation plays a big part in this type of soil degradation.

Buriticupu is now an arid, stony place but it is part of the Amazon rainforest and was once covered in trees, such as cedar, West Indian locust and ipê.

In the 1990s the timber industry was booming here. There were more than 50 sawmills working 24 hours a day. Twenty years later, most of the city’s native vegetation was gone.

“The issue of vegetation is essential, because during a rainy event, it reduces the impact of raindrops”

Geologist and professor at the Federal University of Maranhão

Climate change can exacerbate the process in areas prone to gully erosion as it can lead to more intense rainfall.

Buriticupu is experiencing more violent storms than it used to, according to Juarez Mota Pinheiro, a climatologist at the Federal University of Maranhão.

In the first months of 2023, the state of Maranhão faced one of the worst floods in its history. More than 60 municipalities went into a state of emergency, thousands of people were made homeless and there were dozens of deaths.

“Rainfall intensity is predicted to increase by 10% to 15% [globally by the end of the century]. That may not sound like much, but if you have more and more episodes of extreme rainfall, the dynamics of erosion changes,” says Matthias Vanmaercke, from KU Leuven University in Belgium.

He and his colleague Jean Poesen analysed data from more than 700 gullies around the world and concluded that if extreme rainfall increases by that amount, it could double (or even triple in the worst-case scenario) the risks of gully erosion.

“You’ll have a hard time finding a decent scientist that will not agree with the fact that climate change will probably make this worse,” Prof Vanmaercke says.

Fear of the rain

This phenomenon is affecting people across the world, including millions in Africa.

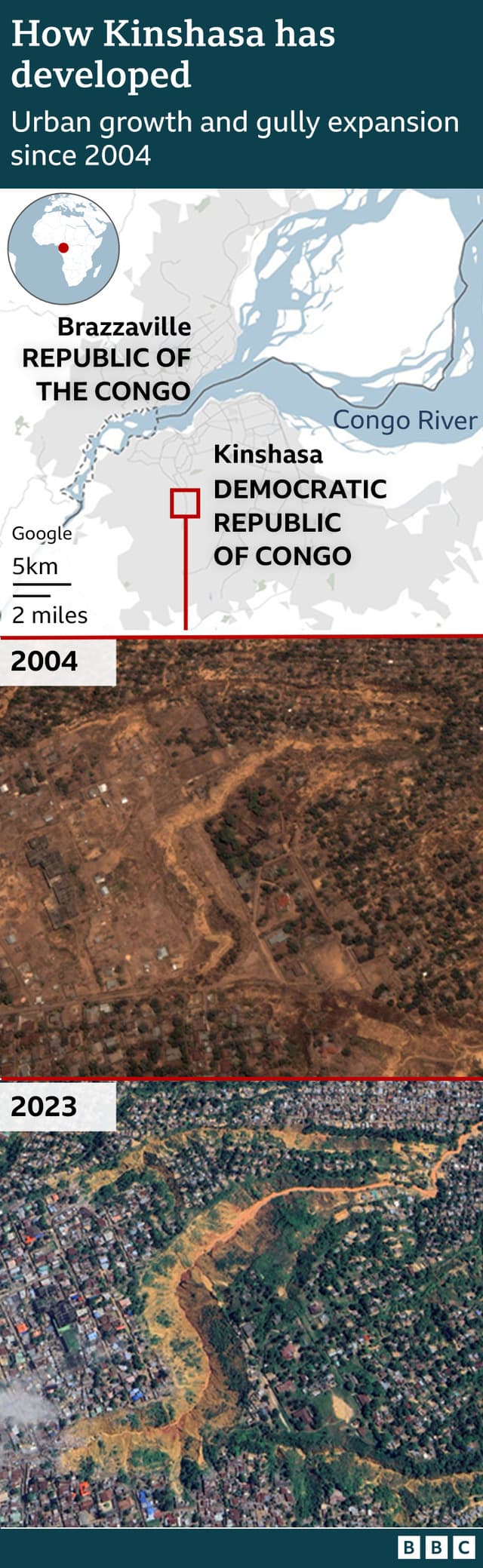

The capital of the Democratic Republic of Congo, Kinshasa, has hundreds of urban gullies – one of which is 2km long. There are more than 165km of gullies in the city, which is home to 12 million people.

In just one night of heavy rain in Kinshasa in December 2022, 60 people died when their homes fell into a ravine.

Alexandre Kadada was there.

“It happened within the space of 30 or 40 minutes. The gully started to open up and all the houses disappeared. The neighbourhood was unrecognisable,” he says.

“My belongings, my house, everything was gone. I only saved my children and my wife.”

Mr Kadada’s neighbour and her four children were among the victims. The woman’s husband was left disabled.

Mr Kadada’s children are now frightened at the slightest hint of bad weather.

“It was the rain that disrupted everything. The rain brought death and despair,” he says.

“We really consider it to be a new geohazard of the Anthropocene,” says Prof Vanmaercke. The Anthropocene is a term used by some scientists to refer to recent times, when human activities have profoundly affected the planet.

The population of Kinshasa is expected to grow to 20 million by 2030 and 35 million by 2050, becoming the largest megacity in Africa, according to the World Bank.

Uncontrolled urban growth can involve cutting down trees – a natural barrier to erosion – and illegal occupation of potentially unstable areas.

In Buriticupu, people also fear the rain.

“There are times when land the size of a house collapses. It makes a violent noise, it shakes everything. Then people cry. The sadness it causes is crazy,” says 52-year-old João Batista, a mechanic who owns a workshop on the edge of a huge gully.

“I’ve lost 40% of my customers. Many are afraid to stop by,” he says. But he refuses to leave.

The voçoroca behind his workshop was once a playground for children, he says, but the gully swallowed everything.

He decided to plant bamboo to try to slow the erosion. But given the scale of the problem, Buriticupu needs much bigger solutions.

What can be done?

However, with the right engineering and investment, “all of this is stoppable”, says Prof Vanmaercke.

To stop gully erosion, cities have to build proper drainage systems to control the flow of rainwater and run-off, explains Prof Poesen, to divert water away from areas vulnerable to gullies.

But these schemes cost money in cities where budgets are tight.

The public prosecutor’s office for Maranhão state is taking legal action against the city of Buriticupu, saying it has not carried out plans that had been agreed.

Buriticupu’s Mayor João Teixeira da Silva declined to comment on the case but says he has requested financial help from the federal government to fund work to divert the flow of rainwater.

The national government told us it was considering whether to release 300m Brazilian reals ($60m; £47m) for Buriticupu. It added that it has already provided 629,000 reals ($125,000; £100,000) to build a canal and storm drain, restore local roads and demolish 89 houses.

The Ministry of Environment says that it has a programme to implement “resilient systems in cities”, but that it is not currently doing anything in Buriticupu.

“These are complex works, works that require large resources,” says the mayor. “What we need is responsibility, both at the municipal, state and federal levels.”

But João Batista is aware that if the gully behind his workshop grows, he may have to move.

“This is nature telling us that if we don’t look after our planet, it will be destroyed. If it keeps raining like this, then we are in God’s hands because there’s nothing we can do.”

Emily Foster is a globe-trotting journalist based in the UK. Her articles offer readers a global perspective on international events, exploring complex geopolitical issues and providing a nuanced view of the world’s most pressing challenges.