Technology

Samsung’s Galaxy Subscription Plan to Launch with S25 Ultra Next Month

Louisiana Records First U.S. Fatality from H5N1 Avian Influenza

Health

The United States has recorded its first human death from the H5N1 bird flu virus, with Louisiana health officials confirming the case …

Disney Acquires Majority Stake in FuboTV to Expand Streaming Reach

Entertainment

In a bold strategic move, Disney has acquired a 70% majority stake in FuboTV, merging it with Hulu + Live TV to …

Zendaya Sparks Engagement Rumors with Golden Globes Appearance

Entertainment

Zendaya turned heads at the 2025 Golden Globe Awards, not just for her stunning fashion choice but for the sparkling diamond ring …

India Detects First HMPV Case in Bengaluru Baby

Health

Bengaluru has become the focal point of India’s first suspected Human Metapneumovirus (HMPV) case after an eight-month-old infant was diagnosed with respiratory …

Winter Storm Causes Widespread Disruptions Across Midwest and East Coast

LifeStyle

Winter Storm Blair has brought snow, ice, and freezing rain to much of the Midwest and East Coast, creating hazardous travel conditions …

Halliday’s AI Smart Glasses Revolutionize Wearable Technology

Technology

Halliday’s debut at CES 2025 has left tech enthusiasts buzzing with excitement as the company unveiled its revolutionary AI-powered smart glasses. These …

What to Know About China’s Human Metapneumovirus (HMPV) Outbreak

Health

China is currently facing a spike in human metapneumovirus (HMPV) infections, predominantly affecting children under 14. The outbreak, as reported by Newsweek, …

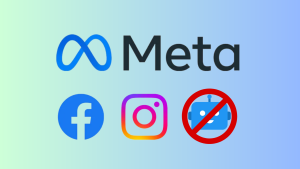

Why Meta Pulled AI Profiles From Facebook and Instagram

Technology

Meta has abruptly discontinued its AI-generated profiles on Facebook and Instagram after facing widespread criticism. Introduced in late 2024, these profiles were …