A single grain of ice ejected from Jupiter‘s ocean moon Europa, if captured by NASA’s forthcoming Europa Clipper spacecraft, could be enough to reveal evidence of alien life, a new experiment suggests.

“With suitable instrumentation, such as the SUrface Dust Analyzer on NASA’s Europa Clipper space probe, it might be easier than we thought to find life, or traces of it, on icy moons,” said Frank Postberg of Freie Universität Berlin in a statement. Postberg is a co-author of a new study describing the findings.

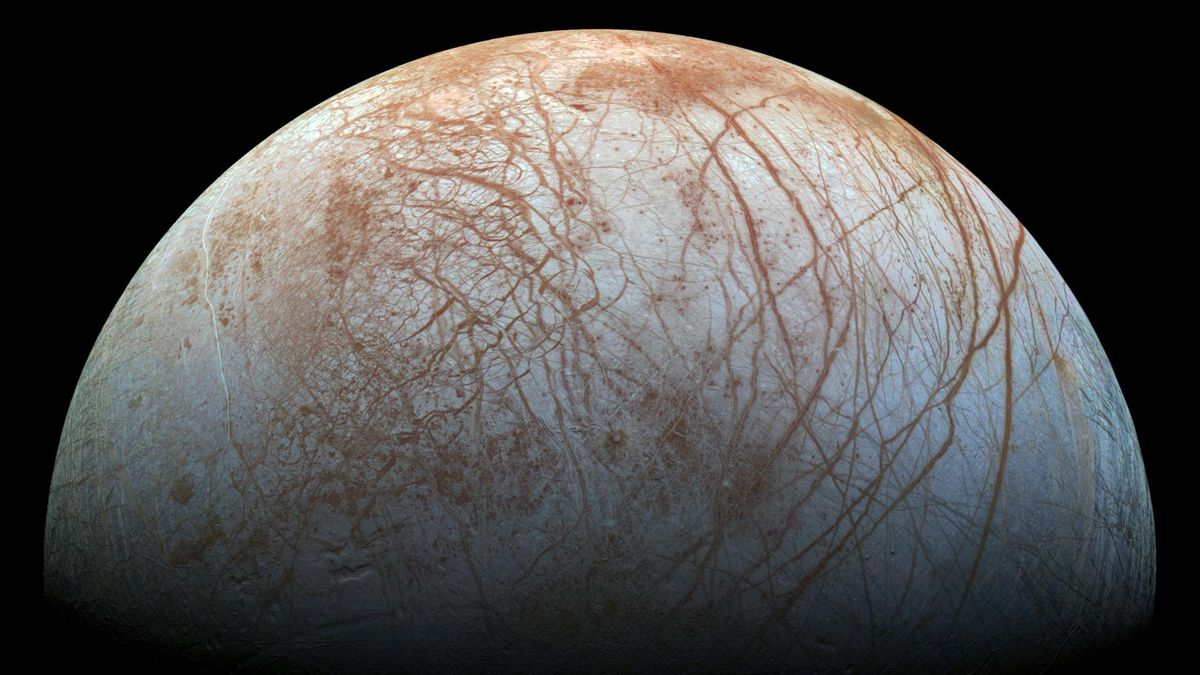

The first dedicated mission to this frozen Jovian moon, Europa Clipper is currently scheduled to blast-off in October 2024. It’s expected to arrive in 2030, then perform nearly 50 close fly-bys of Europa, skimming the icy surface at altitudes as low as 25 kilometers (16 miles). The mission’s primary objective is to learn more about the habitability of Europa’s subterranean ocean and the thickness of the ice shell above it. The mission is not designed to find life, to be clear — but scientists are now realizing there may be a way.

Related: The Weird Plumes of Jupiter’s Moon Europa Are Spewing Water Vapor

One of Europa’s fellow ocean moons is Enceladus, a small, icy body in orbit around the ringed planet Saturn. In 2006, the Cassini mission to Saturn discovered plumes of water vapor belching out from Enceladus’ ocean through large fractures in the surface, nicknamed “tiger stripes.”

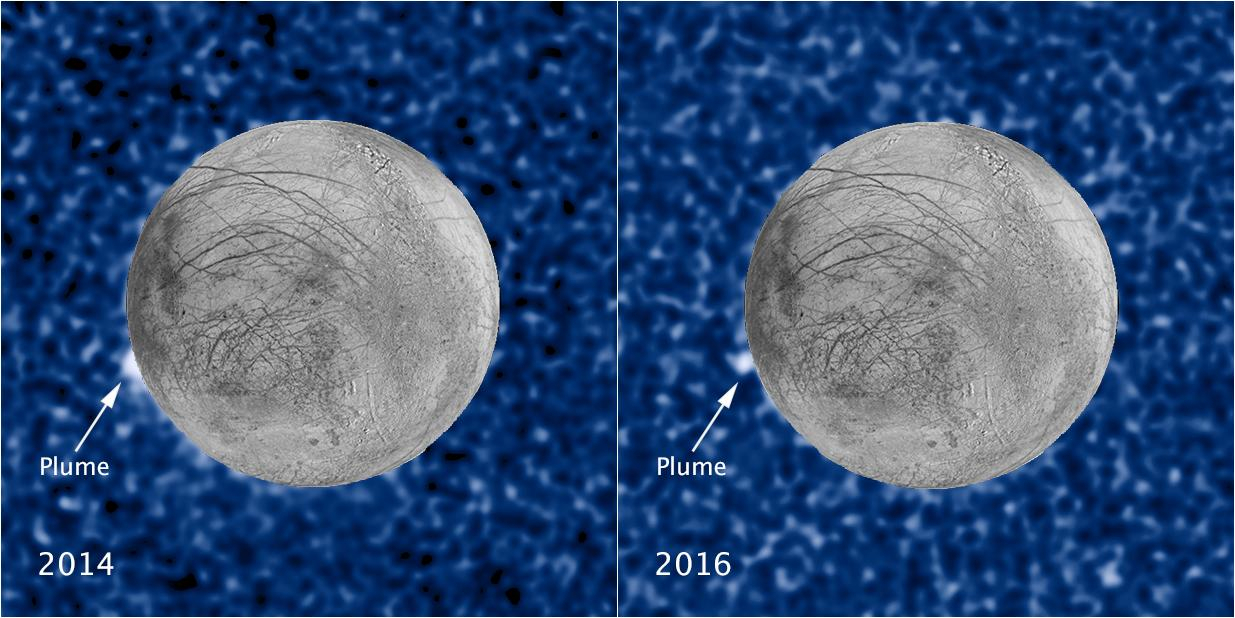

In 2014, the Hubble Space Telescope observed what appeared to be a similar looking plume towering 200 kilometers (125 miles) above Europa’s surface. Two years later, it saw another plume emanating from the same location. Then, in 2018, NASA astronomers revealed that the old Galileo probe,which operated in orbit around Jupiter between 1995 and 2003, had actually flown through a plume.

Under the assumption that Europa Clipper may also fly through an icy moon plume, scientists led by Fabian Klenner of the University of Washington in Seattle investigated whether the spacecraft’s Surface Dust Analyzer (SUDA) might be able to detect any life carried up from the ocean on the plume. SUDA is designed to study particles of Europa’s surface ice and dust sputtered into space as the moon is constantly bombarded by micrometeorites, but perhaps it could analyze ice grains in the plumes, too.

Simulating high-velocity impacts of ice grains on the instrument in a laboratory would be pretty impractical, so instead Klenner’s team fired a thin, fast-moving jet of water vapor loaded with a bacterium called Sphingopyxis alaskensis into a vacuum chamber. Sphingopyxis alaskensis is found in sea waters off the coast of Alaska, and is at home in cold temperatures and while surviving off few nutrients.

It’s one of the closest things we have to a life-form on Earth that could survive in Europa’s ocean.

More pertinently to the Europa Clipper’s potential for finding such life, the bacteria “are extremely small, so they are in theory capable of fitting into ice grains that are emitted from an ocean world like Enceladus or Europa,” said Klenner in the statement.

The vacuum resulted in the water jet disintegrating into droplets that froze as ice grains. The grains were then studied with a mass spectrometer, mimicking how SUDA will study any grains that it picks up in real life. The results of the experiment showed that Sphingopyxis alaskensis, or at least the parts of it that form ocean scum, could indeed be detected from studying just a single ice grain.

“We have shown that even a tiny fraction of cellular material could be identified by a mass spectrometer on board a spacecraft,” said Klenner. “Our results give us more confidence that using upcoming instruments, we will be able to detect lifeforms similar to those on Earth, which we increasingly believe could be present on ocean-bearing moons.”

Europa Clipper’s instruments are not capable of identifying DNA, but SUDA could detect fatty acids and lipids, which can form biological cell membranes. In Earth’s oceans, it is the lipid membranes that contribute to the thin film of ocean scum on the water’s surface. It’s this scum that gives sea-spray its distinctive odor.

“For me, it is even more exciting to look for lipids, or for fatty acids, than to look for building blocks of DNA, and the reason is because fatty acids appear to be more stable,” said Klenner.

If there is life in Europa’s ocean containing lipid membranes, then there’s a greater chance that the biological components can remain in one piece for Europa Clipper to detect.

The findings were published on March 22nd in the journal Science Advances.

Dr. Thomas Hughes is a UK-based scientist and science communicator who makes complex topics accessible to readers. His articles explore breakthroughs in various scientific disciplines, from space exploration to cutting-edge research.