The Hubble Space Telescope has seen cyclones raging in the dynamic atmosphere of a hot Jupiter located 880 light years away, thanks to observations and computer modeling that could one day be applied to characterize weather on smaller, rocky exoplanets.

The planet, dubbed WASP-121b, has a mass about 1.16 times greater than our solar system’s Jupiter and orbits its star at a distance of just 3.88 million kilometers (2.41 million miles). That’s just 2.6% the distance between Earth and the sun. Furthermore, WASP-121b speeds around its star once in only1.27 days. In other words, its year is just 1.27 Earth days long.

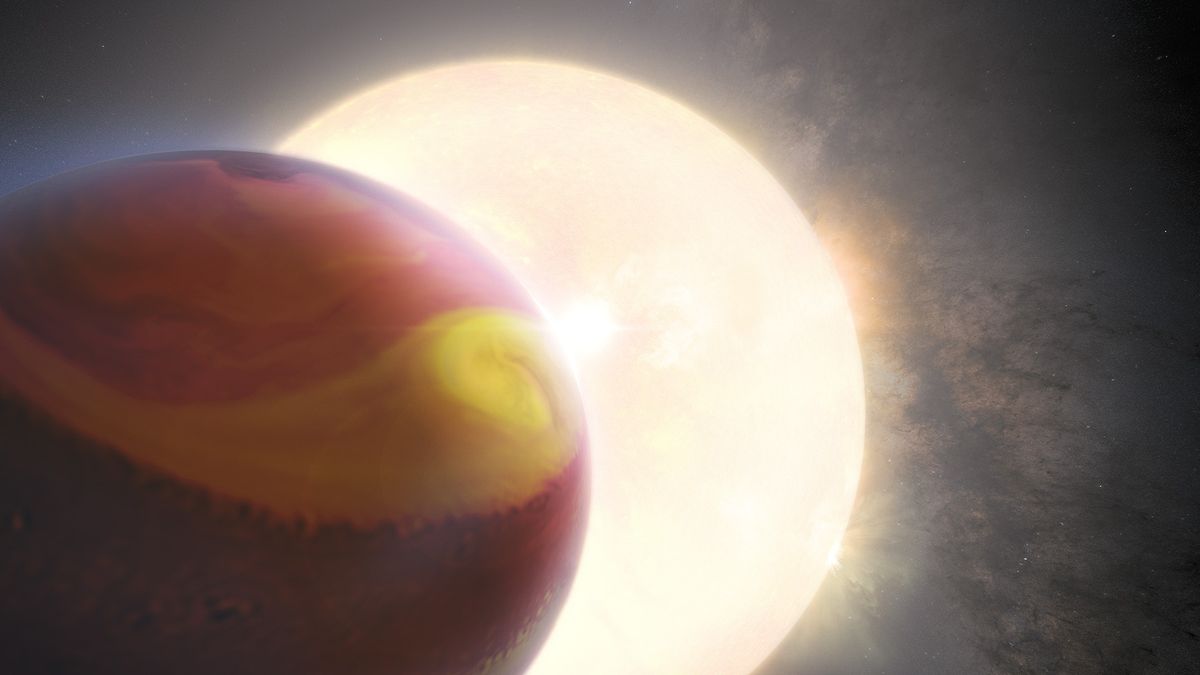

Being so close to its star, WASP-121b is also tidally locked, meaning it rotates on its axis in time with its orbit such that it always shows the same hemisphere to its star. Its permanent dayside reaches temperatures around 2,329 degrees Celsius (4,224 degrees Fahrenheit), causing WASP-121b’s atmosphere to become bloated, expanding the radius of the planet to 75% larger than our beloved Jupiter. In this insufferably hot maelstrom, it is suspected that evaporated iron, barium and oxides of titanium and vanadium lace the world’s atmosphere and form showers of molten metal on weather fronts between the day and night sides.

At such a large size, WASP-121b is also a terrific target for observation.

Related: 30 years ago, astronauts saved the Hubble Space Telescope

The Hubble Space Telescope observed the WASP-121 system on four separate occasions, in June and November 2016, and in March 2018 and February 2019. On each occasion, the planet was in a different position in its orbit, including transiting in front of and disappearing behind its star. This allowed a team of astronomers, led by Jack Skinner of the California Institute of Technology, to determine how WASP-121b changes brightness when seen from different angles and in different phases like our moon.

Then, by applying computer modeling, Skinner and colleagues could determine what the data could reveal about the planet’s atmosphere.

“The remarkable details of our exoplanet atmosphere simulations allows us to accurately model the weather on ultra-hot planets like WASP-121b,” said Skinner in a statement.

Hubble’s observations show that WASP-121b’s atmosphere is dynamic, as the temperature gradient between the permanent dayside and everlasting nightside generate huge storms and cyclones; weather fronts also wash over the planet and regions of hot and cooler air form, grow and mix. These weather features are quasi-periodic, varying over timescales of about five of the planet’s days.

“The information that we extracted from those observations was used to infer the chemistry, temperature and clouds of the atmosphere of WASP-121b at different times,” said Quentin Changeat of the Space Telescope Science Institute in the same statement. “This provided us with an exquisite picture of the planet changing over time.”

It’s not the first time weather has been observed on exoplanets. For example, in 2009, astronomers used the Spitzer Space Telescope to observe another hot Jupiter named HD 80606b, which travels around its star on a 111-day, comet-like — and rather eccentric — orbit that sees it rush close to its star. This causes the world to heat up, generating huge storms in its atmosphere that then die away as the planet recedes from the star.

However, WASP-121b in particular represents a step forward in characterizing weather on exoplanets.

“The assembled data-set represents a significant amount of observing time for a single planet and is currently the only consistent set of such repeated observations,” said Changeat.

While WASP-121b is far too hot to be habitable and, as a gas giant, wouldn’t have a solid surface anyway, the technique used by Skinner and Changeat’s team could one day be scaled down to be applied on smaller, rocky exoplanets. “Studying exoplanets’ weather is vital to understanding the complexity of exoplanet atmospheres on other worlds, especially in the search for exoplanets with habitable conditions,” said Changeat.

In doing so, we won’t just come to know exoplanets better, but we’ll also be able to learn more about the weather on planets in our own solar system such as Jupiter by being able to compare and contrast with what exoplanets are doing.

Dr. Thomas Hughes is a UK-based scientist and science communicator who makes complex topics accessible to readers. His articles explore breakthroughs in various scientific disciplines, from space exploration to cutting-edge research.