There have been all kinds of wild ideas to get spacecraft into orbit. Everything from firing huge cannons to spinning craft at rapid speed has been posited, explored, or in some cases, even tested to some degree. And yet, good ol’ flaming rockets continue to dominate all, because they actually get the job done.

Rockets, fuel, and all their supporting infrastructure remain expensive, so the search for an alternative goes on. One daring idea involves using airships to loft payloads into orbit. What if you could simply float up into space?

Lighter Than Air

The concept sounds compelling from the outset. Through the use of hydrogen or helium as a lifting gas, airships and balloons manage to reach great altitudes while burning zero propellant. What if you could just keep floating higher and higher until you reached orbital space?

This is a huge deal when it comes to reaching orbit. One of the biggest problems of our current space efforts is referred to as the tyranny of the rocket equation. The more cargo you want to launch into space, the more fuel you need. But then that fuel adds more weight, which needs yet more fuel to carry its weight into orbit. To say nothing of the greater structure and supporting material to contain it all.

Carrying even a few extra kilograms of weight to space can require huge amounts of additional fuel. This is why we use staged rockets to reach orbit at present. By shedding large amounts of structural weight at the end of each rocket stage, it’s possible to move the remaining rocket farther with less fuel.

If you could get to orbit while using zero fuel, it would be a total gamechanger. It wouldn’t just be cheaper to launch satellites or other cargoes. It would also make missions to the Moon or Mars far easier. Those rockets would no longer have to carry the huge amount of fuel required to escape Earth’s surface and get to orbit. Instead, they could just carry the lower amount of fuel required to go from Earth orbit to their final destination.

Of course, it’s not that simple. Reaching orbit isn’t just about going high above the Earth. If you just go straight up above the Earth’s surface, and then stop, you’ll just fall back down. If you want to orbit, you have to go sideways really, really fast.

Thus, an airship-to-orbit launch system would have to do two things. It would have to haul a payload up high, and then get it up to the speed required for its desired orbit. That’s where it gets hard. The minimum speed to reach a stable orbit around Earth is 7.8 kilometers per second (28,000 km/h or 17,500 mph). Thus, even if you’ve floated up very, very high, you still need a huge rocket or some kind of very efficient ion thruster to push your payload up to that speed. And you still need fuel to generate that massive delta-V (change in velocity).

For this reason, airships aren’t the perfect hack to reaching orbit that you might think. They’re good for floating about, and you can even go very, very high. But if you want to circle the Earth again and again and again, you better bring a bucketload of fuel with you.

Someone’s Working On It

Nevertheless, this concept is being actively worked on, but not by the usual suspects. Don’t look at NASA, JAXA, SpaceX, ESA, or even Roscosmos. Instead, it’s the work of the DIY volunteer space program known as JP Aerospace.

The organization has grand dreams of launching airships into space. Its concept isn’t as simple as just getting into a big balloon and floating up into orbit, though. Instead, it envisions a three-stage system.

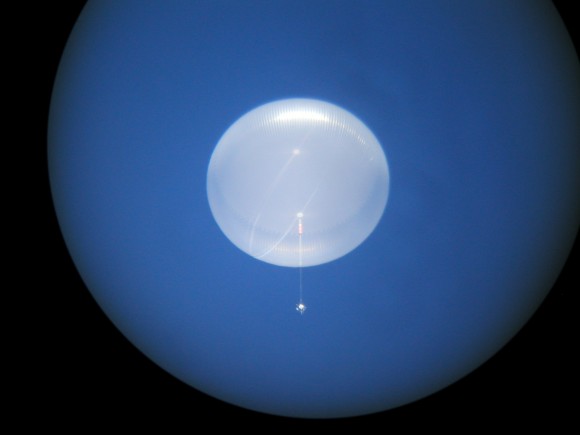

The first stage would involve an airship designed to travel from ground level up to 140,000 feet. The company proposes a V-shaped design with an airfoil profile to generate additional lift as it moves through the atmosphere. Propulsion would be via propellers that are specifically designed to operate in the near-vacuum at those altitudes.

Once at that height, the first stage craft would dock with a permanently floating structure called Dark Sky Station. It would serve as a docking station where cargo could be transferred from the first stage craft to the Orbital Ascender, which is the craft designed to carry the payload into orbit.

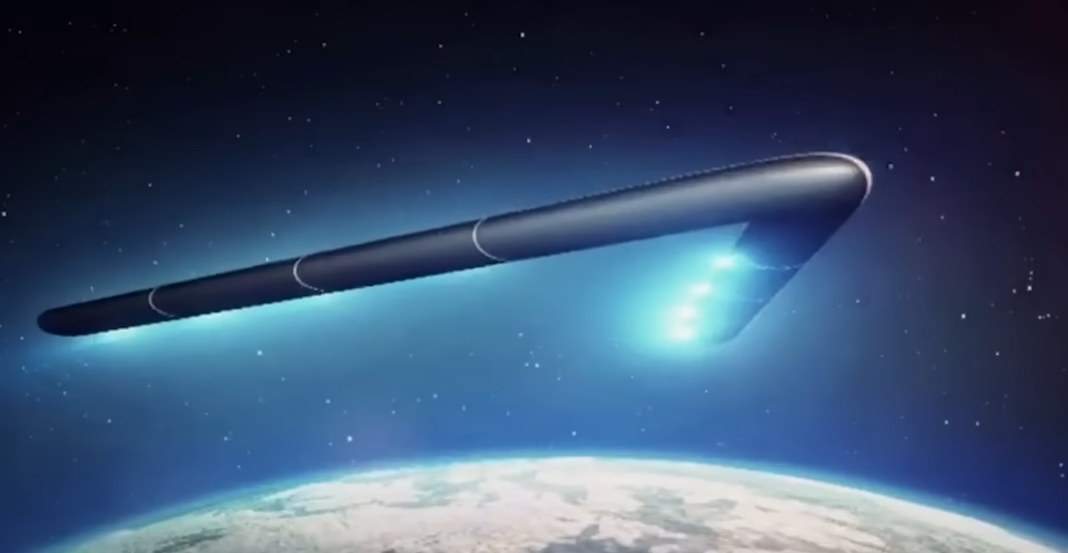

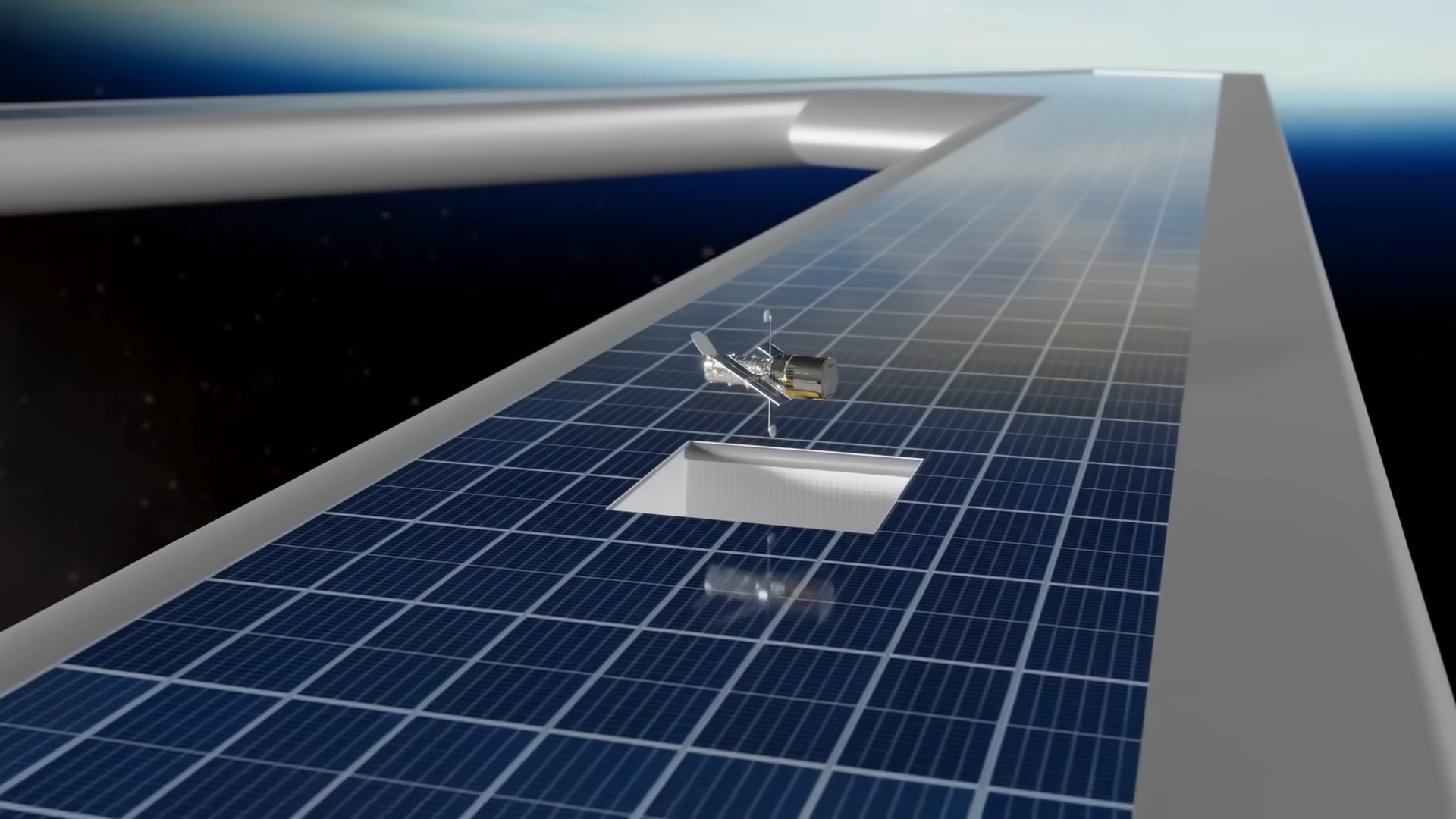

The Orbital Ascender itself sounds like a fantastical thing on paper. The team’s current concept is for a V-shaped craft with a fabric outer shell which contains many individual plastic cells full of lifting gas. That in itself isn’t so wild, but the proposed size is. It’s slated to measure 1,828 meters on each side of the V — well over a mile long — with an internal volume of over 11 million cubic meters. Thin film solar panels on the craft’s surface are intended to generate 90 MW of power, while a plasma generator on the leading edge is intended to help cut drag. The latter is critical, as the craft will need to reach hypersonic speeds in the ultra-thin atmosphere to get its payload up to orbital speeds. To propel the craft up to orbital velocity, the team has been running test firings on its own designs for plasma thrusters.

The team at JP Aerospace is passionate, but currently lacks the means to execute their plans at full scale. Right now, the team has some experimental low-altitude research craft that are a few hundred feet long. Presently, Dark Sky Station and the Orbital Ascender remain far off dreams.

Realistically, the team hasn’t found a shortcut to orbit just yet. Building a working version of the Orbital Ascender would require lofting huge amounts of material to high altitude where it would have to be constructed. Such a craft would be torn to shreds by a simple breeze in the lower atmosphere. A lighter-than-air craft that could operate at such high altitudes and speeds might not even be practical with modern materials, even if the atmosphere is vanishingly thin above 140,000 feet. There are huge questions around what materials the team would use, and whether the theoretical concepts for plasma drag reduction could be made to work on the monumentally huge craft.

Even if the craft’s basic design could work, there are questions around the practicalities of crewing and maintaining a permanent floating airship station at high altitude. Let alone how payloads would be transferred from one giant balloon craft to another. These issues might be solvable with billions of dollars. Maybe. JP Aerospace is having a go on a budget several orders of magnitude more shoestring than that.

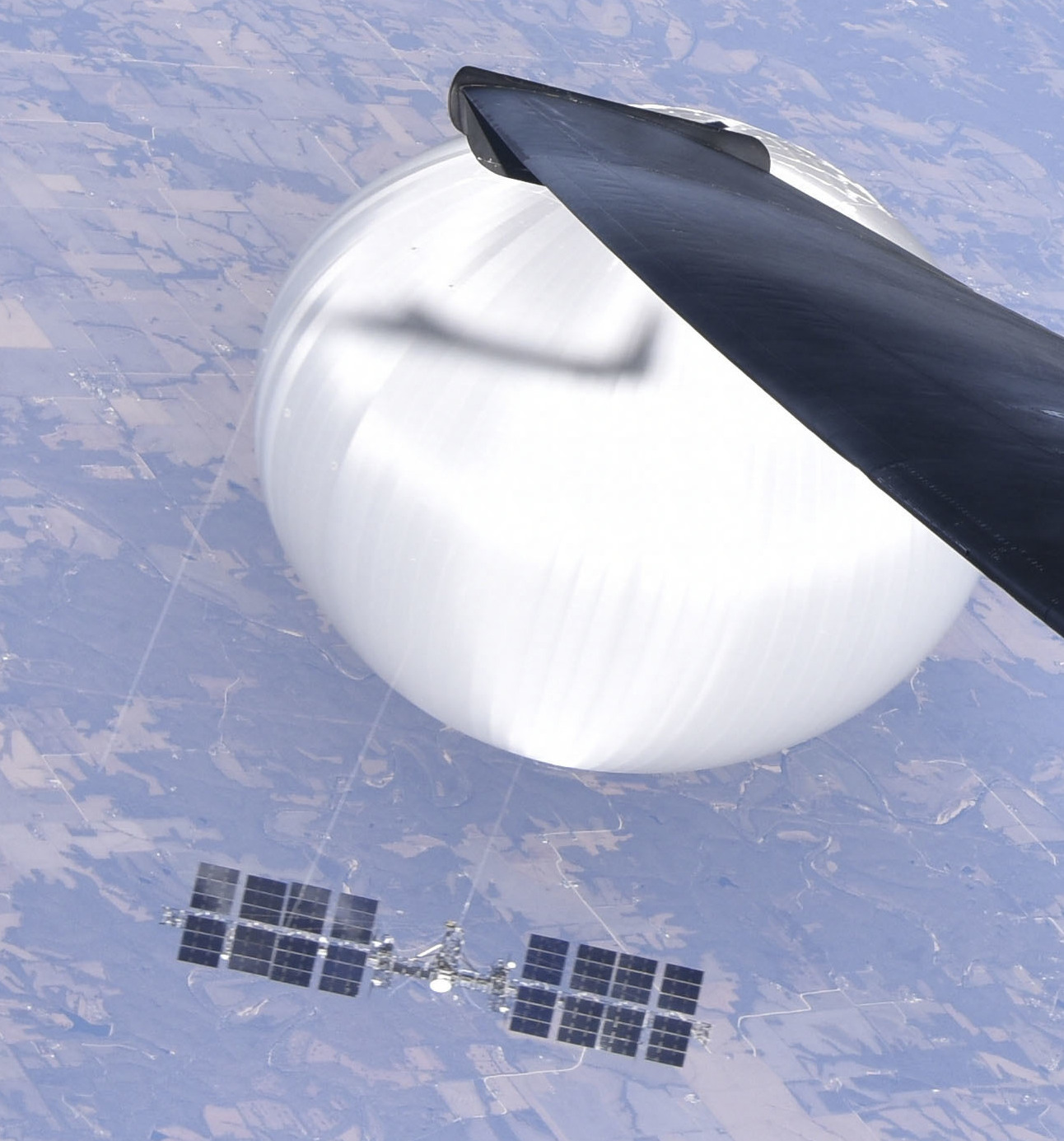

One might imagine a simpler idea could be worth trying first. Lofting conventional rockets to 100,000 feet with balloons would be easier and still cut fuel requirements to some degree. But ultimately, the key challenge of orbit remains. You still need to find a way to get your payload up to a speed of at least 8 kilometers per second, regardless of how high you can get it in the air. That would still require a huge rocket, and a suitably huge balloon to lift it!

For now, orbit remains devastatingly hard to reach, whether you want to go by rocket, airship, or nuclear-powered paddle steamer. Don’t expect to float to the Moon by airship anytime soon, even if it sounds like a good idea.

Dr. Thomas Hughes is a UK-based scientist and science communicator who makes complex topics accessible to readers. His articles explore breakthroughs in various scientific disciplines, from space exploration to cutting-edge research.