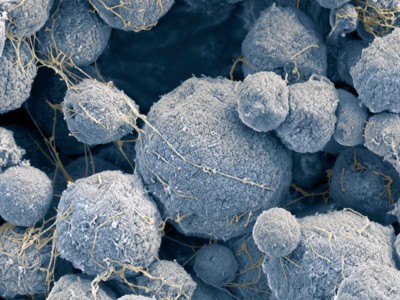

Streptococcus sanguinis bacteria live in the human mouth and are hosts to a newly described group of RNA entities.Credit: UK Health Security Agency/Science Photo Library

The human microbiome just gained a new dimension: scientists have discovered tiny bits of RNA — even smaller than viruses — that colonize the bacteria inside human guts and mouths1. Too minimalistic to be considered a standard life form, these scraps of genetic material are among the smallest known elements to transfer information that can be read by a cell, and the sequences they encode are new to science.

“That’s, like, wildly weird,” says cell and developmental biologist Mark Peifer from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, who was not involved in the work. The research rekindled his sense of the joy that scientific discovery can bring, he says. “The world is just full of new things. And once you start to look, you find them.”

The work was posted on the preprint server bioRxiv on 21 January and has yet to be peer reviewed.

New neighbours

“Obelisks,” as preprint co-author Ivan Zheludev at Stanford University in California and his colleagues are calling the newly-discovered elements, are flattened circles of RNA. The authors’ analysis suggests that these circles are folded into rod-like structures.

Such flattened circles have been seen before in the form of “viroids”, structures made of RNA that are similar to viruses, but much smaller. They were first discovered in the 1970s when some were found to cause diseases in plants. Soon scientists discovered a similar element that can cause hepatitis in humans. More recently, a flurry of studies have reported viroid-like elements in a range of animals2,3 and fungi4, and a 2023 study5 provided the first hint that they might also be present in bacteria.

Massive DNA ‘Borg’ structures perplex scientists

Zheludev and his colleagues took advantage of the characteristic circular RNA of viroids to search for similar elements in databases of RNA from human stool. And there they found the Obelisks.

Although Obelisks have the same shape as many viroids, their genetic sequences are very different — implying that they comprise a separate but related group. Follow-up searches turned up a plethora of Obelisks in stool samples taken from people across every continent. In samples from 472 individuals, most of them from North America, the authors found that 6.6% of people carried Obelisks in their gut microbiota and 53% carried them in their oral bacteria.

The study is “a milestone” because it presents the best available evidence that such elements are widespread in the bacterial world and not just in more complex organisms, says molecular biologist Joan Marquez-Molins at the Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences in Uppsala, who was not involved in the work. “It’s not really something sporadic or isolated in the population — it’s really affecting a considerable amount of the sample,” he says.

Tipping the balance

Nobody knows how Obelisks might affect human health. The various components of the microbiome — including bacteria, fungi and other organisms — “all exist in a balance,” says virologist Anamarija Butković at the Pasteur Institute in Paris, who was not involved in the work. “It’s interesting to think what Obelisks are doing there, and how they might affect this whole balance.”

Answer could come from the common mouth bacterium Streptococcus sanguinis, in which the researchers found a family of Obelisks. Because S. sanguinis is easy to grow, Marquez-Molins and Buković hypothesize that scientists might be able to use these bacteria to address questions about how Obelisks replicate, how they affect bacteria and what their proteins do.

Such experiments could reveal truths about the origin of life itself. Some scientists have speculated that because viroids and their relatives are small, simple and have the capacity to self-replicate, they are the precursors of all life on Earth, Butković says. Although scientists have just seen Obelisks for the first time, they might have shaped us from the start.

Dr. Thomas Hughes is a UK-based scientist and science communicator who makes complex topics accessible to readers. His articles explore breakthroughs in various scientific disciplines, from space exploration to cutting-edge research.