Thus far 2023 has not had much to offer in terms of any bright comets.

Apart from the much-ballyhooed green comet C/2022 E3 (ZTF) in January and comet C/2023 P1 (Nishimura) in September, which were both either faint or poorly placed, there has been nothing that has been readily visible either with just a simple pair of binoculars or even the naked eye.

But barring an ever-possible newcomer, comet 12P/Pons-Brooks should soon come within the reach of small telescopes and even binoculars. And it may even brighten to naked-eye visibility during March.

Related: Volcanic ‘Devil Comet’ erupts with its biggest blast yet as it races toward Earth

First sighting: 1812

It was on July 21, 1812, that French astronomer Jean Louis Pons discovered a comet of magnitude 6.5, near the border of two rather dim constellations, Camelopardalis and Lynx. (Magnitude indicates an object’s degree of brightness. The lower the figure of magnitude, the brighter the object.) Pons also described his find as a shapeless object with no tail.

A little more than three weeks later, the comet reached naked-eye visibility and by the end of August it had brightened to magnitude 4.5 with a nearly two-degree tail. During September, the comet reached magnitude 4.0, while the tail split and lengthened slightly to 3 degrees. Observations ended after Sept. 28, due to the comet plunging far to the south and out of view for most northern observers.

Several astronomers tried to calculate the comet’s orbit. All showed it to be a periodic comet traveling around the sun in a highly elliptical loop with a period of roughly 65 to 75 years. Many astronomers accepted Johann Encke’s estimate of 70.68 years as the best, which set the comet’s return in early 1883, but searches at that time proved fruitless.

Back with a “flare” in 1883

The story picks up on Sept. 2, 1883 when American comet observer William R. Brooks accidentally found it while he himself was searching for comets. Initially it was rather faint at magnitude 10.0 and was thought to be a new comet until the first orbital calculations showed it to be identical to comet Pons.

It was during this apparition that the comet demonstrated its most intriguing characteristic: its ability to produce unexpected outbursts in brightness. On Sept. 22, the comet went from magnitude 11.0 to 8.0 – a nearly 16-fold jump in brightness. Its appearance also changed from diffuse to star-like. The comet soon became visible to the naked eye by Nov. 20 and brightened up to a magnitude of 3.0.

Additional outbursts were reported on Jan. 1, 1884 and Jan. 19. On the latter date, M. Charles Trepied at Algiers Observatory, made a detailed sketch of 12P/Pons-Brooks” coma depicting a sharply defined nucleus with two jets resembling a horseshoe, emanating from it. The comet passed closest to the sun (perihelion) on Jan. 26, then it steadily faded thereafter. It was last seen on June 2, 1884.

More surprises in 1953-54

Several orbital calculations were made after the 1883-84 apparition with predictions indicating that the comet would return in 1954. When the comet was recovered en route to the sun on June 20, 1953, it was very faint at magnitude 17.5. But in the weeks that followed, it again underwent several outbursts in brightness, most notably on July 1st when overnight it became 100 times brighter! On April 23, the comet had an estimated magnitude of 6.4 and its tail was half a degree long. 12P/Pons–Brooks reached perihelion on May 22, 1954 when it was 158 million miles (254 million km) from Earth. After perihelion it became better visible from the Southern Hemisphere.

Orbital characteristics

At perihelion comet 12P/Pons-Brooks is only about three-quarters the Earth’s distance from the sun, while at the far end of its orbit (aphelion) it lies beyond the orbit of Neptune. In shape and size, the orbit resembles that of the famous Halley’s Comet, though Halley travels in a retrograde direction (opposite that of the planets).

Three other comets – 13P/Olbers, 23P/Brorsen-Metcalf, and the now defunct 20D/Westphal (it disappeared rapidly in 1913 and was not seen at its predicted return in 1976) – all have similar orbits and are sometimes referred to as Neptune’s family of comets. If these comets are indeed related, then after Halley, 12P/Pons-Brooks is intrinsically the brightest compared to the other four.

A “devil” of a comet

So far, 12P/Pons-Brooks has been under scrutiny for more than three years, having been recovered on June 10, 2020 by the Lowell Discovery Telescope in Arizona. When first sighted, the comet was magnitude 23.0 – or about 6.3 million times fainter than an object on the threshold of naked eye visibility. The comet has since brightened to around magnitude 10.0, making it a target for moderately-large telescopes.

But it’s expected to brighten still further in the weeks and months to come.

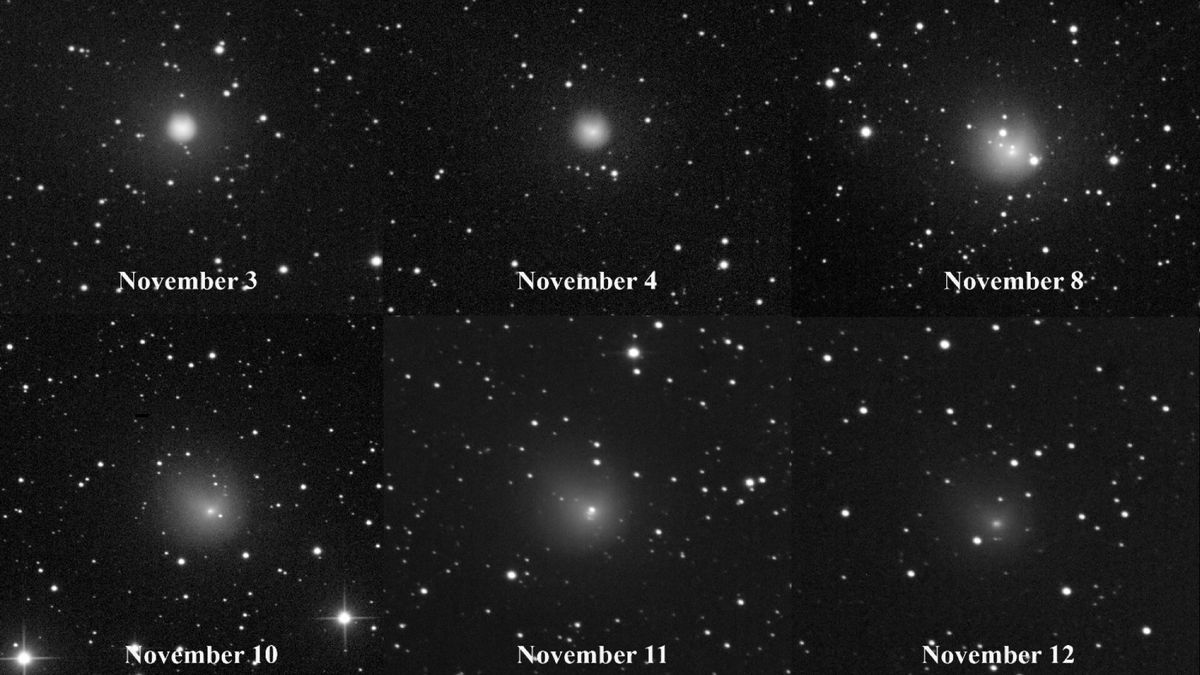

And 12P/Pons-Brooks is also up to its old tricks regarding sudden flare-ups in brightness. On July 20, an unexpected brightness outburst again caused it to briefly become about 100 times brighter and, in similar fashion to what was seen in 1884 from Algiers Observatory, its coma expanded to resemble for some, a horseshoe.

Others, however, suggested a horseshoe crab, the Millennium Falcon from Star Wars or even – as many news media outlets have since christened it – the horns of a devil, a.k.a. “The Devil’s Comet.”

Another similarly large outburst occurred on Oct. 5, and still yet another outburst occurred on Oct. 31.

What would induce these sudden brightness surges?

The exact cause is unknown, though the best guess is that perhaps a fissure develops on the comet’s nucleus, due to a build-up of gas – carbon monoxide and dioxide – from inside the comet’s nucleus. Eventually the gas breaks through the surface and results in a jetting of about 22 billion pounds (10 billion kg) of dust and ice out into space. Since dust and ice are excellent reflectors of sunlight, the comet suddenly appears to get much brighter.

Coming attractions

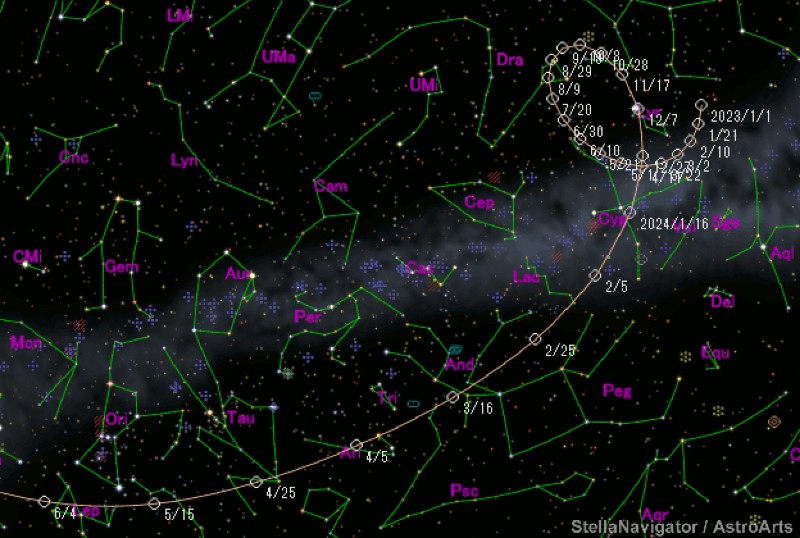

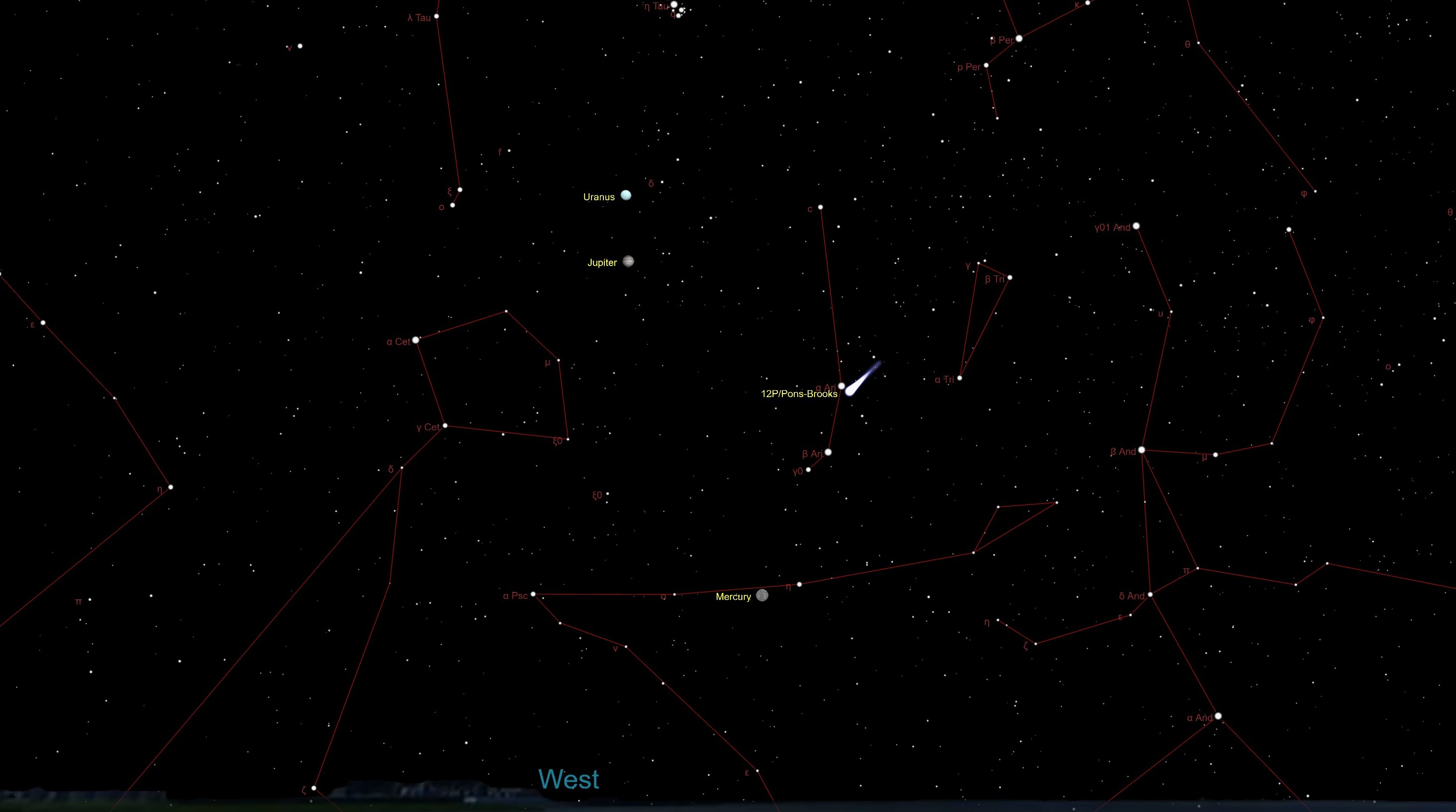

Throughout the rest of the fall and into the upcoming winter, the comet will move slowly southeast through the constellations of Lyra and Cygnus, while gradually brightening from 10th to perhaps 7th magnitude by the end of February. By the first week of March, it will have moved into the boundaries of Andromeda in the early evening sky, hovering about 20-degrees above the west-northwest horizon at the end of evening twilight.

With the aid of a good sky chart and a dark sky, it should be readily accessible in binoculars. Its apparent night-to-night motion will now be accelerating as it draws nearer to the sun. By mid-month, it will have shifted into eastern Pisces; now perhaps a 6th-magnitude object, it should be a fine sight for binoculars.

And by the end of March, it may brighten to 5th-magnitude, reaching naked-eye visibility against the backdrop of the zodiacal constellation of Aries. By now, a short tail may also have formed.

(Image credit: Seiichi Yoshida)

On the evenings of March 30 and 31, 12P/Pons-Brooks will pass very close to Aries’ brightest star, 2nd-magnitude Hamal; use this star as a benchmark to find the comet. On the 30th, the comet will sit a half-degree to the star’s lower right, while on the 31st it can be found 0.7-degree to its upper left. Look quick, however, because Hamal and the comet will be rather low in the sky at the end of evening twilight, just 12-degrees above the west-northwest horizon.

Thereafter, the comet will disappear into sunset glow during April and will arrive at perihelion on April 21 at a distance of 72.6 million miles (116.8 million km). 12P/Pons-Brooks passes 22-degrees northeast of the sun in mid-April, but then will fade very rapidly and largely become an object for Southern Hemisphere observers. It will have probably dropped to 6th or 7th magnitude by the end of May and 8th or 9th magnitude by the end of June.

If you want to see comet 12P/Pons-Brooks or any other comet in the night sky for yourself, our guides to the best telescopes and best binoculars are a great place to start.

And if you’re looking to take photos of comet 12P/Pons-Brooks or the night sky in general, check out our guide on how to view and photograph comets, as well as our best cameras for astrophotography and best lenses for astrophotography.

The X factor

Of course, the biggest variable that could have the most significant impact on the comet’s brightness is the possibility of more outbursts in the coming weeks and months. This is especially true if a major outburst were to take place during March; literally overnight comet 12P/Pons-Brooks could suddenly become very bright with a large starlike head and perhaps even a striking tail – or a series of rays – hovering low in the west-northwest evening sky.

This certainly cannot be ruled out, although based on previous apparitions, such major brightness surges seem to be confined chiefly to when this comet is far from the sun and still quite faint. But while the odds seem long for such a flare-up as the comet gets nearer to the sun, the chance – however small – for 12P/Pons-Brooks to suddenly blossom into a truly spectacular object, certainly makes it all the more worthwhile to keep tabs on it for the remainder of this year and on into early 2024. We’ll just have to wait and see what happens.

If this story has a moral, we can quote the legendary comet expert Fred L. Whipple (1906-2004):

“If you must bet, bet on a horse, not on a comet.”

Joe Rao serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York’s Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, the Farmers’ Almanac and other publications.

Dr. Thomas Hughes is a UK-based scientist and science communicator who makes complex topics accessible to readers. His articles explore breakthroughs in various scientific disciplines, from space exploration to cutting-edge research.