Today, Earth is home to animals of all shapes and sizes, from nearly microscopic creatures like tardigrades to 80-foot-long (25 meters) blue whales. These organisms have arisen and evolved over millions of years of evolution. But what was the first animal on the planet?

The answer to this question is heavily debated by scientists. Dozens of different studies using everything from chromosome evolution over time to ancient fossils have boiled it down to two candidates: sponges and comb jellies.

Some of the best information about early animals comes from fossils dating back to the Cambrian period, which started around 541 million years ago. During this time, Earth experienced a burst of new species during the Cambrian explosion: In just 10 million years, hundreds of thousands of animal species suddenly sprung into being. Almost every type of animal body plan that exists today evolved during the Cambrian explosion, including early arthropods, mollusks and even chordates, which later gave rise to vertebrates. Exquisitely preserved specimens from a rock formation known as the Burgess Shale in British Columbia give us a window into what these early animals looked like.

But all of those species didn’t just come out of nowhere. In the 1950s, previously discovered fossils were identified as animal remains from the Ediacaran period, which extended from around 635 million years ago to the dawn of the Cambrian 541 million years ago.

Unlike the hard exoskeletons found in many of the Cambrian fossils, the animals that lived during the Ediacaran were mostly soft-bodied, blob-shaped animals like cnidarians — a group that includes animals like jellyfish and sea anemones — worms, and possibly sponges. Soft tissues are extremely difficult to preserve because they degrade more easily than bones or exoskeletons. This means that Ediacaran animals’ fossil remains are not only scant, but a lot more difficult to parse. Perhaps the best known of these is a wormlike animal called Dickinsonia, which looks like a large dinner plate with ribbed segments emanating from its center.

Before then, things start to get murky. “Beyond [the Ediacaran], no one’s really looking,” Elizabeth Turner, a paleobiologist at Laurentian University in Ontario, told Live Science. Part of the problem, she explained, is that scientists don’t really know what to look for. “We’re primates; we do pattern recognition,” she said. She thinks the earliest animal fossils probably had little or no recognizable pattern.

Related: What were the first animals to have sex?

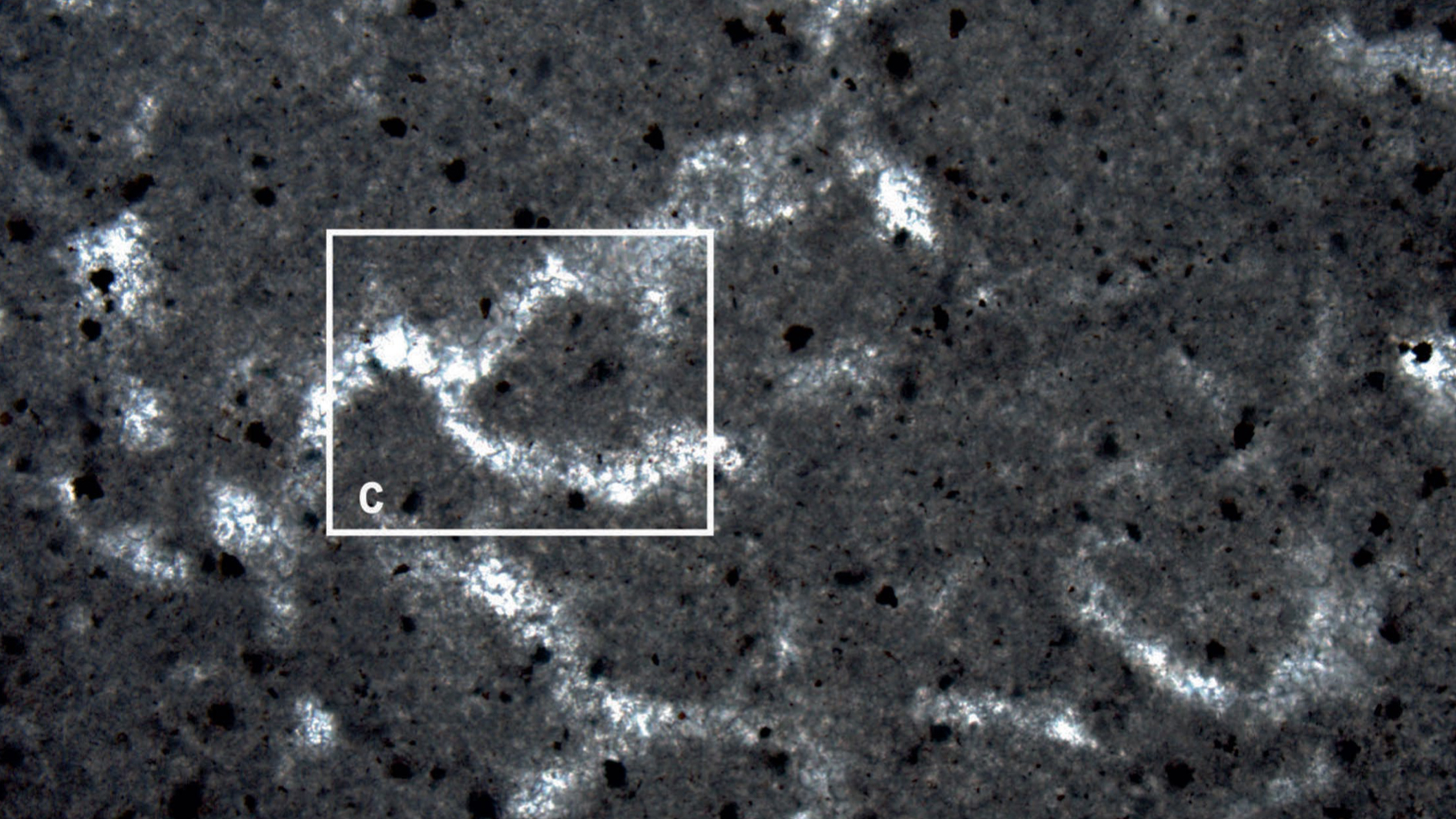

Turner presented what she proposes as the oldest known animal — a fossil specimen of what she says is an 890 million-year-old sponge — in a 2021 paper in the journal Nature. However, not everyone agrees with her hypothesis.

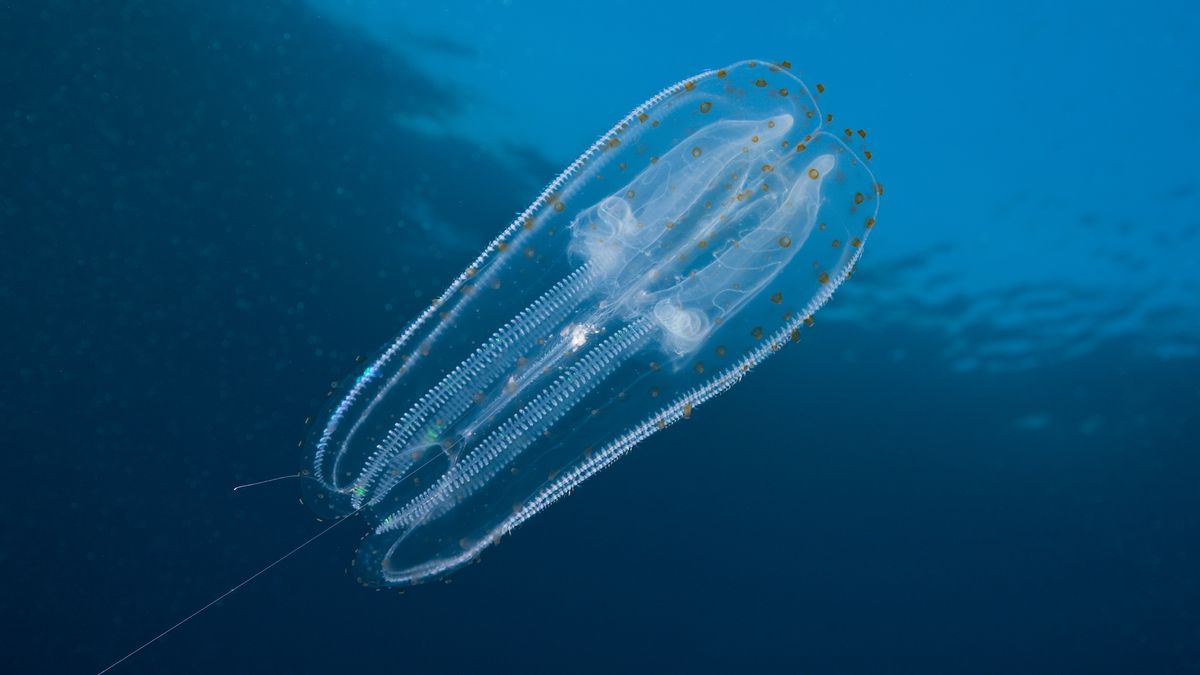

All of the evidence mentioned about early animals thus far comes from fossils found in rocks that can be radiometrically-dated using their isotopes, which degrade at a constant rate over time. But recently, a new method using a model called the molecular clock has risen to prominence. Based on the assumption that genes mutate at a constant rate over time, scientists can analyze modern animal genomes and trace them back to when they first came to be. A 2023 study using chromosomal data from modern ctenophores — otherwise known as comb jellies — argues they were the first known animals, emerging around 600 million to 700 million years ago.

However, Nick Butterfield, a paleogeobiologist at the University of Cambridge, has doubts about both theories. If there were animals 890 million years ago, he said, we would see traces like biomineralization, in which molecules from animals’ organic matter can cause surrounding minerals to crystallize. But the earliest known biomineralization dates to only 750 million years ago.

On the other hand, Butterfield is unsure whether the study on ctenophores offers concrete proof that comb jellies were the earliest animals. “Molecular clocks don’t provide data; they provide hypotheses,”‘ he said. Over the years, studies using different genes have come up with conflicting results supporting either ctenophores or sponges. So Butterfield is hesitant to grant comb jellies the crown based on the most recent study alone.

Even if the ancestors of comb jellies were the first animals, Butterfield doubts they looked the way they do now. Modern comb jellies have complex structures like muscular and neural systems, which more basic animals like sponges lack.

“Things don’t spring forth fully formed from the head of Zeus with muscle systems and neural systems and so on; that’s not how evolution works,” he told Live Science. “The simplest way of being an animal is to be a sponge-like filter feeder. That’s how you have to start off.”

Turner also said that the earliest animal wouldn’t have won any beauty pageants. “It would have looked like a microscopic bit of slime,” she said.

Dr. Thomas Hughes is a UK-based scientist and science communicator who makes complex topics accessible to readers. His articles explore breakthroughs in various scientific disciplines, from space exploration to cutting-edge research.