Image source, Getty Images

- Author, Abdujalil Abdurasulov

- Role, BBC News

- Reporting from Kyiv

-

Ukraine is now allowed to use Western weapons to hit targets inside Russia. What will this decision change and how will it affect the front line in Ukraine?

Up until now, Western countries restricted the use of their weapons to military targets located inside Ukraine, including Crimea and occupied territories. They were concerned that attacking targets across the internationally recognised border with weapons provided by Nato countries would escalate the conflict.

But the latest Russian advance in the north-eastern Kharkiv region convinced Kyiv’s allies that in order to defend itself, Ukraine must be able to destroy military targets on the other side of the border as well.

Last month, Russia launched a massive ground assault in the region, opening a new front and capturing several villages. The Russian advance posed a serious threat to Kharkiv, Ukraine’s second-largest city, which is just 30km away from the border.

The border in this region is effectively the front line as well, so the ban on using Western weapons to hit targets beyond Ukraine enabled Russian troops to prepare for that operation in a safe environment.

Following the growing pressure from Ukraine and other European states, the US agreed to change its policy and allow Kyiv to strike Russia with Western weapons.

“The hallmark of our engagement has been to adapt and adjust as necessary, to meet what’s actually going on on the battlefield, to make sure that Ukraine has what it needs, when it needs it,” US Secretary of State Antony Blinken said during a meeting of Nato foreign ministers in Prague on Friday.

Image source, Getty Images

Just a few days before this announcement, Russian President Vladimir Putin threatened to expand “sanitary zones” in case Western long-range weapons are used to strike the Russian territory.

He said that Nato countries in Europe must remember that they have “states with small territories and dense population”.

“They must take this factor into consideration prior to discussing strikes deep inside the Russian territory,” he added.

Avoiding an escalation is probably the reason why the US didn’t include long-range weapons such as ATACMS (Army Tactical Missile Systems) in its permission to strike Russia. These missiles have a range of 300km and could be used to hit military bases and airfields well into Russian territory.

Such limitations leave Ukraine with only the option of focusing on targets near its border. But this is still a major policy shift by Kyiv’s main allies.

Even with a shorter range – up to 70km – multiple rocket launchers such as HIMARS can significantly disrupt Russian logistics operations and troops movement, which will ultimately slow down any offensive plans.

Now, Ukraine can “strike places where the enemy concentrated its troops, equipment and supply storage facilities that are used to attack Ukraine,” says Yuriy Povkh from the Kharkiv tactical group that co-ordinates military operations in the north-east.

Earlier this week, Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky stated that Russia was gathering its troops just 90km from Kharkiv for another offensive.

And the Institute for Study of War analysed satellite images and confirmed that there were “expanded activities at depots and warehouses” in that area. So the ability to target those facilities will seriously strengthen the capacity of Ukrainian forces to repel new attacks in the region.

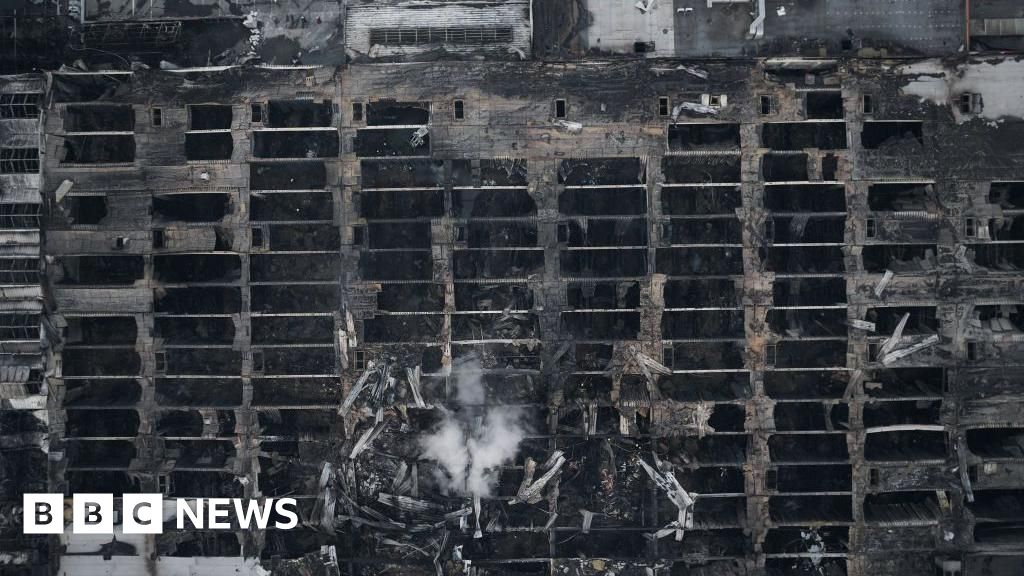

Lifting the ban on Western weapons, however, is unlikely to help to protect Ukraine from Russian glide bombs known locally as KAB. They have a devastating effect and are regularly used to bomb Kharkiv and other border towns. But to stop such attacks, Ukrainian forces must target planes that drop those deadly KABs.

Image source, Getty Images

The only weapon capable of intercepting those planes that Ukraine has at its disposal at this moment is the US air-defence system Patriot. However, getting this weapon close to Kharkiv is a huge risk. Spy drones can quickly spot it and Moscow can launch missiles such as Iskander to destroy this expensive system.

Interestingly, the UK and France, which provide Ukraine with jointly made Storm Shadow air-launched cruise missiles (or Scalp as they are called in France), haven’t explicitly restricted their use. And their range can go up to 250km. In fact, French President Emanuel Macron told journalists last week:“We should allow [Ukraine] to neutralise the military sites from which the missiles are fired and, basically, the military sites from which Ukraine is attacked.”

And such rhetoric is seen as permission to use Storm Shadows/Scalps, a military aviation officer who prefers to remain anonymous, told the BBC. So, he says, Ukraine can now hit airfields in the Kursk and Belgorod regions that border Ukraine.

However, such operations will be limited in terms of what they can achieve. Ukrainian Su-24s that are equipped with these cruise missiles will have to get close to the Russian border in order to launch them, which makes them vulnerable to Russian air defence systems. F-16 jets that are expected by the end of this year are better equipped for such tasks. But President Zelensky admits that it’s still not clear whether Ukraine’s partners will allow these jets to be used to attack targets in Russia.

“I think that using any weapon, Western kind of weapon, on the territory of Russia is a question of time,” he said at the Nordic summit in Stockholm on Friday.

Ukrainian forces are trying to develop their own weapons to hit targets in Russia’s rear. Some of their drones have attacked oil depots and military facilities hundreds of kilometres away from the border.

The latest attack was on a long-range radar station in the city of Orsk, which is 1800km from the Ukrainian border.

Emily Foster is a globe-trotting journalist based in the UK. Her articles offer readers a global perspective on international events, exploring complex geopolitical issues and providing a nuanced view of the world’s most pressing challenges.