More practitioners are needed to support the open-science movement to disseminate materials such as bacterial DNA plasmids.Credit: Daniela Beckmann/Science Photo Library

Lenny Teytelman can still recall his days as a PhD student 20 years ago when he accessed public databases for his studies in yeast genetics. “My research would be technically impossible had researchers not deposited their data into the National Center for Biotechnology Information,” says Teytelman, the co-founder of protocols.io, a platform for open-access protocols, based in Berkeley, California. (Protocols.io was acquired by Springer Nature, which publishes Nature, last July.)

Open science is a broad term that refers to the movement of making the entire research life cycle freely available to everyone, from citizens and students to research professionals. This includes sharing research plans, protocols, materials, data and papers through open-access platforms.

Who should pay for open-access publishing? APC alternatives emerge

The practice of open science is on an upswing. PLOS, a non-profit publisher of open-access journals, found that the rates of data-repository use rose from 22% in 2019 to 28% in 2022 for more than 71,000 papers published in its journals during that time. The rates of preprints associated with published articles also increased, from 15% in 2019 to 24% in 2022. A 2006 study that analysed close to 1,500 published papers found evidence that open-access articles had higher numbers of citations by peers than did non-open-access articles published in the same journal after controlling for factors such as field, the number of authors and journal impact factor (G. Eysenbach PLoS Biol. 4, e157; 2006).

Although many researchers wholeheartedly embrace open-access publishing, the open sharing of laboratory materials, reagents and protocols has seen a slower adoption, mostly owing to a lack of awareness on how to properly share them and poor incentives. A paper published in September last year in Nature Communications found that the majority of more than 22,000 survey participants had favourable attitudes towards open research (J. Ferguson et al. Nature Commun. 14, 5401; 2023). Of the participants, 90% had engaged in at least one open-science practice such as sharing data and code. Compared with a decade ago, open-science practices had increased from 49% in 2010 to 87% in 2020.

However, there is a disparity between attitudes and behaviours. Across all disciplines represented in the survey — economics, political science, psychology and sociology — the percentage of researchers who had openly shared their data and code was much lower than the percentage of researchers who supported the idea of open research.

Melina Fan, co-founder and chief scientific officer of DNA-sharing platform Addgene, says that such organizations can smooth and speed the process of sharing lab materials.Credit: David Fox Photography

“Translating beliefs about open access into behaviours is challenging,” says Melina Fan, co-founder and chief scientific officer of Addgene, a non-profit platform for researchers to share DNA experimental materials called plasmids, in Watertown, Massachusetts. But repositories such as Addgene can play an important part in enabling resource sharing, she says. “Repositories lower the barrier to sharing and provide the infrastructure needed to change research culture.”

Open-science organizations

Tsuyoshi Nakagawa, a plant geneticist at Shimane University in Matsue, Japan, found that a gene cloning kit worked particularly well to introduce genes into plants by means of plasmids. “As I worked in a research support centre in the university, it felt natural for me to share my experience and materials with the community,” he says.

“However, after I started sharing [plasmids], I received too many requests which took time away from my work.” To save time, he started using Addgene, which facilitated the distribution of the plasmids. Since 2016, Nakagawa has deposited more than 80 plasmids on Addgene.

How a simple idea to share lab materials led to a circular-economy movement in science

The sharing of tangible scientific resources, such as plasmids, requires a materials transfer agreement. When researchers share materials such as proteins and chemicals across institutions, the process of material transfer can take weeks or months. Open-science organizations such as Addgene help to complete all legal paperwork pertaining to material transfer behind the scenes in a few days to facilitate the sharing of scientific materials, including plasmids, antibodies and viruses.

Fan says that Addgene can enhance quality control on top of being a distributor. “When we receive plasmids from depositors, we sequence them to ensure that the sequences match what the depositors claim. This is important for reproducibility and transparency.” Fan also recommends that scientists deposit their materials in global repositories that are well established and financially self-sustaining, to better extend the reach and longevity of materials.

Nakagawa advises scientists to check with representatives from open-science organizations and experienced colleagues when there are concerns. For instance, he worked with Addgene staff to ensure that the organization could internally reproduce the plasmid materials he wanted to share. “While funders and publishers can demand researchers to share through policies, open-science institutions and communities play a pivotal role to promote a research culture that normalizes sharing practices,” says Teytelman.

David Mellor is director of policy at the Center for Open Science in Charlottesville, Virginia.Credit: Center for Open Science

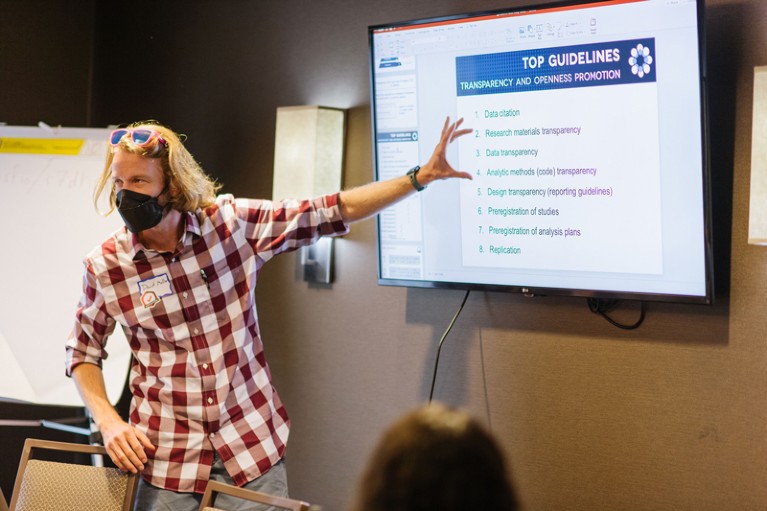

The Center for Open Science, a non-profit organization in Charlottesville, Virginia, aims to achieve exactly that by following a ‘theory of change’ philosophy. “Our strategy consists of five steps: making open-science practices possible, easy, normal, rewardable and eventually a requirement,” says David Mellor, director of policy at the centre. “The first activity in our strategy for culture change is to develop infrastructure to enable sharing, followed by an easy-to-use ‘user interface’ that makes it easier to share.”

For example, researchers can register their studies on the Open Science Framework registry, the centre’s open-sourced web platform. The centre has helped to create communities for researchers who are taking on open science, such as the Society for the Improvement of Psychological Science, as a way for them to see open-science practices as typical and inherent parts of research.

The centre’s staff have also thought of ways to incentivize open science, such as gathering evidence of sharing, which researchers can add to grant proposals, and ways for journals to prioritize the peer review and acceptance of registered studies.

Winning over the sceptics

In addition to the view that sharing materials adds to the workload, sceptics also criticize open-access platforms that rely solely on the research community to self-police standards for giving credit when due in the form of citations, authorships and acknowledgements. The absence of active enforcement of such standards might discourage some researchers from sharing. The use of tracking technology can help to change the minds of those who are worried about not getting credit for their work (see ‘Five tips on how to share laboratory materials effectively’). For example, protocols.io has introduced metrics including the number of article views and citations, and it gives an option for users to vouch for the reliability of protocols.

Another reason that researchers are hesitant to participate in open science is poor awareness and even negative sentiments surrounding the movement, particularly in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs). Magaret Sivapragasam, who used to work as a senior lecturer and process engineer at Quest International University in Ipoh, Malaysia, says that in her country, the concept of open science is still new compared with North America and Europe.

“Researchers in Malaysia have the impression that you pay to publish in open-access journals, which is associated with predatory journals. I do not want the quality of my work to be judged like that,” says Sivapragasam, who is now a master’s student in science communication at the University of the West of England in Bristol, UK. Even so, she admits that open science has benefited her work. “When I was doing research, I was always accessing open databases to know the toxicity levels of compounds and to cross-check my experimental data [with those] from other labs.”

Lamis Elkheir shares a similar experience to Sivapragasam. As a pharmaceutical chemistry lecturer at the University of Khartoum, Sudan, and a PhD student in a joint programme between the University of Tours in France and the Mycetoma Research Center in Khartoum, Elkheir says that there is limited awareness of the open-science movement in many African countries. “This leads to a scarcity of opportunities for open-science discussions with my friends and colleagues,” she says. “However, I believe that grassroots initiatives can change this.” Leveraging the training she received from the open-access publisher eLife, Elkheir helped to organize the Global Dynamics in Responsible Research virtual symposium in December 2022, which focused on equity in research, open-science efforts in LMICs and multilingualism in open science.

Magaret Sivapragasam says open science benefited her engineering research in Malaysia.Credit: Universiti Teknologi PETRONAS

Sivapragasam suggests that to win over sceptics in LMICs, open-science organizations should interact directly with local researchers. “Agencies can empower researchers in developing nations with training and resources to raise awareness. Open science is a global effort, and no one should be left behind,” says Elkheir.

Is there a good reason not to share?

Although sharing benefits science in general, there might be instances when it is not appropriate to share materials, such as when labs and biotechnology firms want to commercialize their technology and are concerned about proprietary rights over their data and materials.

Open science, done wrong, will compound inequities

“Although we increasingly talk about open science, in practice, there is a spectrum of openness that exists,” says Fan. “The terms of sharing can be legally defined to protect commercial interests while advancing open science.”

A great example is the invention of the CRISPR gene-editing tool. As soon as the papers related to the technology were published, the various research groups involved deposited the plasmids on Addgene, which saw a huge spike in demand for them. Around the globe, thousands of researchers tested the plasmids for all sorts of applications. “I would argue that open sharing in this instance produced data that demonstrated to investors that the technology worked,” adds Fan. In November last year, the world’s first CRISPR gene-editing therapy, Casgevy, was approved in the United Kingdom to treat sickle-cell disease and transfusion-dependent β-thalassaemia.

In research, academic reputations are so highly valued that researchers might be overly cautious about sharing data and methods that are not yet fully reproducible. Mellor suggests that more education around the idea that science is a work in progress could help to convince open-science holdouts. “I am optimistic that as we see more researchers engaging in open science, sharing will become a norm,” he says. “We will see the community driving the open-science movement in the future to achieve reproducible and equitable research.”

Dr. Thomas Hughes is a UK-based scientist and science communicator who makes complex topics accessible to readers. His articles explore breakthroughs in various scientific disciplines, from space exploration to cutting-edge research.