- By Katy Watson

- South America correspondent, Piauí, Brazil

The Brazilian authorities rescued more than 3,000 workers last year

Carnauba wax is a product you may not have heard of, but you have almost certainly consumed it – it is added to sweets to stop them melting, to pills to make them easier to swallow and as a thickener in lipstick and mascara.

Workers in Brazil’s poor north-eastern state of Piauí rely on harvesting wax from carnauba palm trees to earn a living. But the power is in the hands of big business who, authorities say, are turning a blind eye to exploitation.

Seven cars are driving in convoy across Piauí’s arid landscape known as the Caatinga – sparse, often thorny vegetation on dusty, dry land.

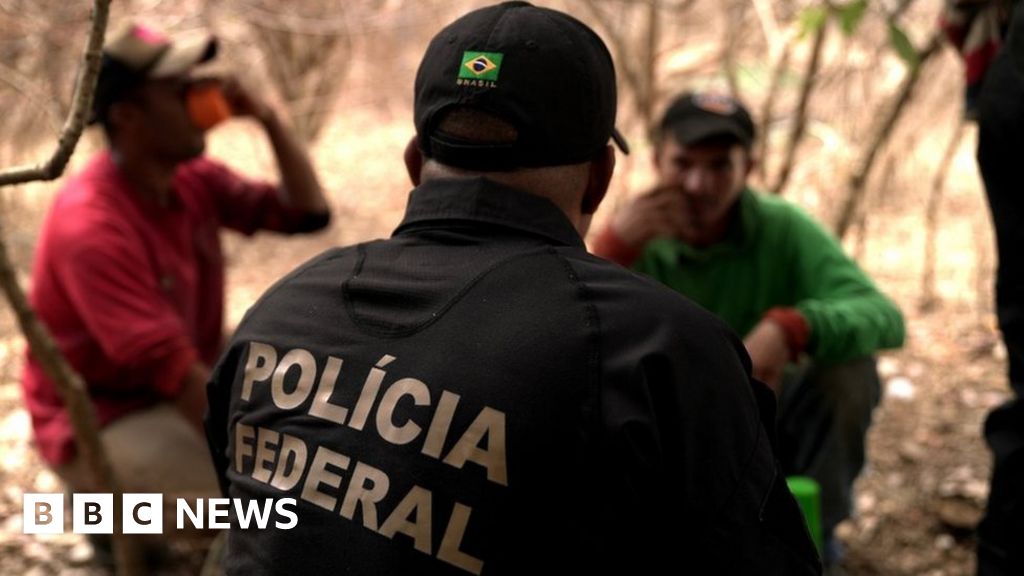

In the convoy, there are inspectors from the labour ministry, federal police and prosecutors. This is the culmination of several months of secret on-the-ground investigations into working conditions in the carnauba wax industry.

Gislene Melo dos Santos Stacholski is leading the raid. She is part of a mobile deployment unit that carries out raids to rescue people working under conditions considered to be similar to slave labour in Brazil.

She has been doing it for 11 years and carnauba plantations take up much of her time.

“Carnauba harvesting is a painful activity because the working conditions under the sun in the northeast aren’t easy,” Gislene says. “It’s extremely manual, heavy work, using hand tools.”

Carnauba palm trees are scattered all over Piauí, the world’s biggest producer of the wax, and several neighbouring states. The industry sustains the lives of around half a million Brazilians, harvesting the wax in universally difficult conditions.

Last year, 114 workers were rescued from carnauba plantations, Brazilian government figures show – a nine-year high. The numbers suggest slave-like labour is an increasing problem across industries, hitting the highest number since 2009 with 3,190 rescues.

In Brazil’s penal code, the definition of slavery is not just forced labour, it’s also debt bondage, degrading work conditions and long hours that risk workers’ health.

According to the International Labour Organization, such conditions are common in rural areas of Brazil and are closely connected to poverty.

After three hours on the road, we arrive at an accommodation block – its ceilings so low you cannot stand up in some parts. There are walls with crumbling plaster and bare electrical sockets. Outside, pigs wallow in the waste water thrown out of the kitchen.

A short distance away, we find most of the workers sitting under a large tree, sheltering from the midday sun.

Most of the workers were hired off the books

“Who’s in charge here?” asks Gislene. Some mumble a name. Others are wearing green t-shirts which give it away: “EDMILSON STRAWS”. But Edmilson is nowhere to be seen.

One by one, the inspectors interview the men. Of 19, only two are officially on the books. The rest work cash-in-hand, receiving 70 reais ($14; £11) a day – barely enough to make a living year-round for the workers who, outside of the harvesting period, often tend to their own crops.

“It’s so hot,” says Irismar Pereira, one of the unregistered workers. “We stop for a bit because otherwise the sun would kill us – we can only cope with so much.”

Tree of thorns

Gislene clocks that one of the plastic water containers has the words “only with medical prescription” stamped on it, indicating the workers are drinking from an old medicine bottle.

After a meagre lunch – rice and chicken feet – the men get back to work. Using handmade scythes attached to the end of a long bamboo pole, they cut down the leaves at the top of the palms.

The carnauba palm’s nickname in the Tupi indigenous language is the tree of thorns. You need to wear gloves to avoid injury.

Several workers say they were not given any safety equipment: “If you’re registered, the boss buys protective equipment for you,” José Airton explains to the officers. “But in my case, I had to buy my own.”

It is difficult, dangerous work – the inspectors point out that the workers appear to have little training.

The rooms the workers were staying in had broken electricity sockets and broke labour laws

Back at the accommodation block, the boss, Edmilson da Silva Montes, has turned up. He is angry he has been caught.

“The government needs to give small producers like me more of a chance,” he says. “I have been fighting to survive for some time now. The costs of producing this wax are more than what I receive.”

Gislene hands him a fine of $30,000 (£23,700) for 15 infractions, including slave-like labour conditions, failing to register workers, not providing sufficient work clothes, no drinking water, unsafe electricity supply, illegal contracting of workers, poor accommodation and insanitary conditions.

But Edmilson is adamant he is doing his best, despite this being the third time he has been caught.

After a debrief, Gislene tells the workers they are free to go home. Few of them are happy though: despite the bad working conditions, there is little choice – this is the only way they earn money.

The authorities say the high level of informality in the industry makes tracing the carnauba wax back to big companies a difficult task.

In 2016, the ministry of labour, concerned with the number of workers they were rescuing in difficult conditions, asked the five biggest wax processing companies to sign an agreement committing themselves to improving the supply chain and ending this informality.

The biggest processor that signed is Brasil Ceras, a company that counts L’Óreal as one of its clients. According to Brazilian authorities, producers who were found to have employed workers in conditions comparable to slave labour say they sold wax to Brasil Ceras, even after the company signed the agreement with authorities. But there is no paper trail linking these producers to Brasil Ceras.

The ministry of labour says one explanation is that, legally, small producers who work as a family unit do not have to submit a paper trail when they sell their wax. And Brasil Ceras says it only buys from families and companies that can prove they comply with labour laws.

Its client L’Óreal has told the BBC it is committed to ethical sourcing and has an audit programme with its suppliers to ensure due diligence.

The Carnauba palm’s nickname in Tupi is the tree of thorns – harvesting its leaves is dangerous, back-breaking work

But police and prosecutors argue that despite committing to responsible sourcing, no company buying from the carnauba industry – big or small – can profess to have a clean production chain because of the widespread informality of the harvesting.

“The companies we investigate that transform the carnauba powder into wax and sell it to the multinationals, I guarantee you that despite signing social responsibility commitments, they don’t care like they should,” says Federal Police investigator Milena Caland, who is based in Piauí.

“Of the investigations I am looking into, none are registered providers – it’s all illegal.”

Inspector Gislene Melo dos Santos Stacholski thinks that without backing from foreign industry – nearly all of the wax produced in Brazil is exported – little can be done.

“The precariousness comes from the top down,” she says. “There’s what we call deliberate blindness. It’s comfortable for the industry not to see the problems, because they don’t need to act, they don’t need to invest, they don’t need to pay.”

Additional reporting by Jéssica Cruz

Emily Foster is a globe-trotting journalist based in the UK. Her articles offer readers a global perspective on international events, exploring complex geopolitical issues and providing a nuanced view of the world’s most pressing challenges.