A recent study published in Behavioral Neuroscience offers new insights into the relationship between brain structure and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). The study found that smaller volumes in specific regions of the hippocampus, a brain structure involved in memory and learning, are associated with reduced PTSD symptom severity over time. This counterintuitive finding suggests a complex relationship between hippocampal structure and PTSD symptoms, particularly in how these brain regions may influence symptom improvement.

PTSD is a mental health condition that can develop after experiencing or witnessing a highly distressing or traumatic event. It is characterized by symptoms such as reexperiencing the trauma through flashbacks or nightmares, avoiding reminders of the event, emotional numbness, and heightened arousal or anxiety. PTSD can significantly impact a person’s daily life, affecting their ability to function normally in social, occupational, and other important areas.

Previous research has suggested that the hippocampus might be linked to PTSD. However, the relationship between hippocampal structure and long-term changes in PTSD symptoms has been less clear. The new study aimed to explore whether specific subfields of the hippocampus could predict changes in PTSD symptoms over a prolonged period, providing deeper insights into the neurobiological mechanisms underlying the disorder.

“We were interested in this topic because, in our veterans with PTSD, we wanted to predict who was more likely to reduce PTSD symptoms over time and who was more likely to have chronic or worsening symptoms,” explained study author Joseph DeGutis, a health scientist at the VA Boston Healthcare System and associate professor at Harvard Medical School.

“Previous studies have consistently implicated the hippocampus, a brain structure critical to learning and memory, as having an important role in the development and maintenance of PTSD. Advances in structural MRI data analysis have also allowed automated segmentation of hippocampal subregions (subfields) that have different roles in learning and memory (e.g., fear learning vs. pattern completion).”

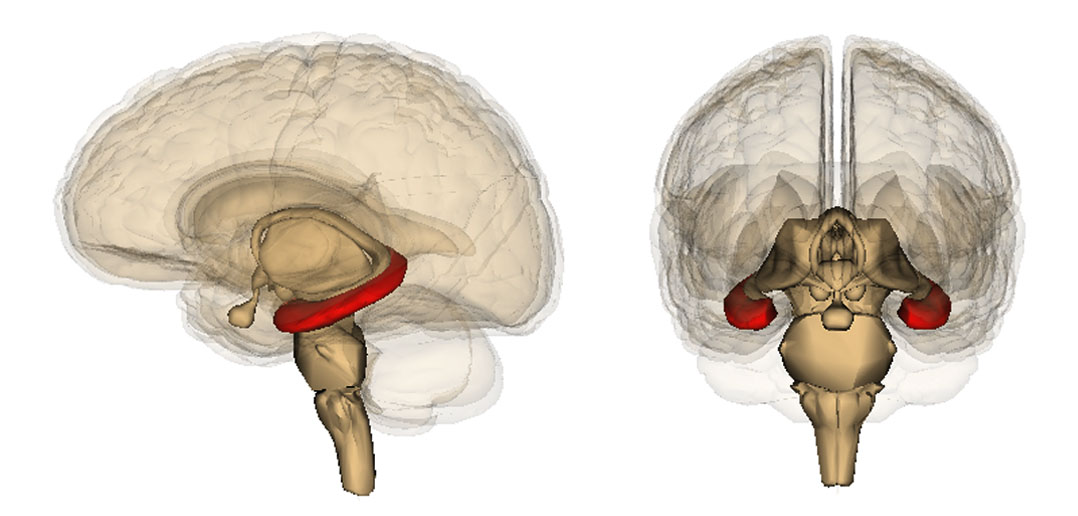

For their study, the researchers recruited 252 post-9/11 veterans, including 159 with PTSD and 93 without. Participants underwent two assessments approximately two years apart. During these assessments, PTSD symptoms were measured using the Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale (CAPS), a widely used diagnostic tool. Additionally, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans were conducted to measure the volumes of different hippocampal subfields, specifically the cornu ammonis (CA) regions CA1 and CA3, and the dentate gyrus.

To ensure the accuracy of their findings, the researchers used an advanced imaging analysis tool called FreeSurfer, which provides detailed volumetric measurements of hippocampal subfields. They also accounted for potential confounding factors such as age, sex, head size, and scanner type.

Contrary to the initial hypothesis, the researchers found that smaller volumes in the CA1-body and CA2/3-body regions of the hippocampus were associated with greater reductions in PTSD symptom severity over time. These associations were specific to changes in avoidance and numbing symptoms, rather than reexperiencing or hyperarousal symptoms. This suggests that smaller volumes in these hippocampal subfields might somehow facilitate the improvement of certain PTSD symptoms.

“Several previous MRI studies have found that a larger overall hippocampus (brain structure critical to learning and memory) protects the individual from developing PTSD after exposure to a traumatic event,” DeGutis told PsyPost. “However, our results show that, if you go on to develop PTSD, smaller volumes of subregions of the hippocampus (CA1, CA3) are predictive of PTSD symptoms improving over time.

“In other words, a larger hippocampus and its subregions may be beneficial to keep you from developing PTSD but if you do go on to develop PTSD, larger hippocampal subregions can be related to having more chronic/worsening symptoms.”

“We were surprised that smaller hippocampal subfields predicted better PTSD outcomes!” DeGutis said. “It suggests that the risk factors for developing PTSD are different from the factors that predict whether you recover from PTSD once you have it. Our results provide a more complex and nuanced understanding of the role of the hippocampus in PTSD. ”

Interestingly, the study did not find significant associations between hippocampal volume and other factors such as combat exposure, treatment history, or time since deployment, indicating that the observed relationships were robust and not influenced by these variables.

The study challenges the traditional view that larger hippocampal volumes are always better in the context of PTSD. But, as with any study, there are some limitations to consider. The sample consisted predominantly of male veterans, which raises questions about the generalizability of the findings to other populations, such as females or civilians.

Another limitation is the timing of the assessments. The first assessment took place an average of three years after the participants’ return from deployment, which means the study did not capture changes in hippocampal volume immediately following trauma. This makes it difficult to determine whether the smaller hippocampal volumes were a pre-existing condition or a consequence of prolonged PTSD.

The long-term aim of the research is “to try and figure out, in those with a PTSD diagnosis, who improves over time and who doesn’t,” DeGutis explained. “This has important mechanistic implications for models of PTSD but also tells us who to target with focused treatments. It is expensive for everyone to get an MRI scan of their brain and we are currently testing whether these brain differences observed can be seen on memory tasks that can be made widely available.”

The study, “Less Is More: Smaller Hippocampal Subfield Volumes Predict Greater Improvements in Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Symptoms Over 2 Years,” was authored by Joseph DeGutis, Danielle R. Sullivan, Sam Agnoli, Anna Stumps, Mark Logue, Emma Brown, Mieke Verfaellie, William Milberg, Regina McGlinchey, and Michael Esterman.

Sarah Carter is a health and wellness expert residing in the UK. With a background in healthcare, she offers evidence-based advice on fitness, nutrition, and mental well-being, promoting healthier living for readers.