There’s an oft-quoted maxim that youngsters growing up on farms have a much stronger immune system than those growing up in cities. The idea is that they are exposed to far more dirt and eat food much closer to the field than their urban cousins. Without the help of a handy microbiologist or epidemiologist it’s difficult to judge its veracity, but personal experience suggests that the bit about dirt may be true at least.

It’s Dangerous To Idealise The Past.

It’s likely that the idea of rural kids seeing more bugs may come from the idea that those in the cities consume sterile processed food from the supermarket, it plays into a notion of an idealised past in which a somehow purer diet came more directly from its source. Somehow so the story goes, by only eating pasteurised and preserved foods, city dwellers are eating something inferior, stripped of its goodness. There’s a yearning for a purer alternative, something supermarkets are only too happy to address by offering premium products at elevated prices. So, was the diet of the past somehow more wholesome, and are those kids having their future health ruined by Big Food? Perhaps it’s time to turn back the clock a little to find out.

It’s likely everyone knows that food spoils if left unattended for long enough. Some foods, such as grain, can last a long time if kept dry, while others such as milk will go bad quite quickly. Milk in particular goes bad for two reasons; firstly because it’s an excellent bacterial growth medium, and secondly because it contains plenty of bacteria by its very nature. Even very clean cows have bugs.

If you lived in most large cities in the nineteenth century, the Industrial Revolution had likely placed you far enough from the nearest cow that your milk had a significant journey to make to reach you even with up-to-date rail transport. Without refrigeration, during that journey it had become a bacterial soup to the extent that even though it might not yet have gone sour, it had certainly become a bacterial brew. It was thus responsible for significant numbers of infections, and had become a major health hazard. So much for the purer diet consumed by city kids of the past.

Heat ( and Louis Pasteur) To The Rescue

The knowledge that heat can be used to preserve food can be traced back hundreds or even thousands of years, and by the nineteenth century that had been developed into the bottling and canning processes which we use today. These rely on sealing food into a container, and cooking it in the container by placing it in boiling water, with the result being a can of perfectly cooked and preserved food which only requires heating to serve.

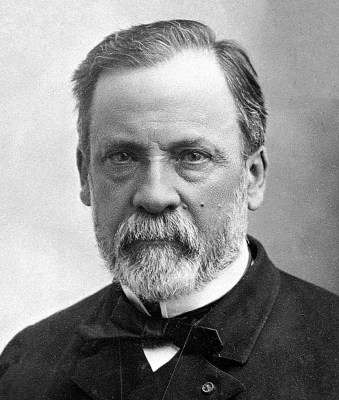

Canning and bottling then have solved food preservation, but only for cooked food. Foodstuffs such as milk or juice don’t survive the process very well, as they cook, and their taste and texture is altered. Think of the taste of condensed milk, for example, which doesn’t quite make an acceptable substitute for fresh milk. And here we come to pasteurisation, the process of heating to a lower temperature for long enough to deactivate bacteria but not long or hot enough to cook the foodstuff. It’s the invention of the French biologist Louis Pasteur, and though we now associate it with milk, it was devised to stop wine from spoiling as it aged.

The beauty of pasteurisation is that it does not require specialised machinery to work; while it’s achieved commercially by passing the milk through steam-heated pipes, it can even be done in a saucepan on a domestic stove. The aim is to heat it as hot as possible without cooking the milk, and the exact temperature depends on for how long it will be heated. The result isn’t the sterility of a high-temperature canned food, but the active bacteria have been removed and its shelf life increased significantly. My experience with the process comes from home-pressed apple juice, and the figure I remember was 67 Celcius, the exceeding of which would impart an apple sauce taste to the final product.

Pasteurisation then is a major contributor to our public health. Far from bring a process somehow denying the kids a more wholesome food, it’s one of the reasons why many of the diseases that haunted our great-grandparents generation are now just names in print. Examining the process has provided a window into the perception of food though, as someone who did grow up on straight-from-the-cow unpasteurised milk did I have a better start in life? Probably not, but it did give me a keen sense of smell for soured cream.

Header image: Agriculture And Stock Department, Information Branch, Photography Section, Public domain.

Sarah Carter is a health and wellness expert residing in the UK. With a background in healthcare, she offers evidence-based advice on fitness, nutrition, and mental well-being, promoting healthier living for readers.