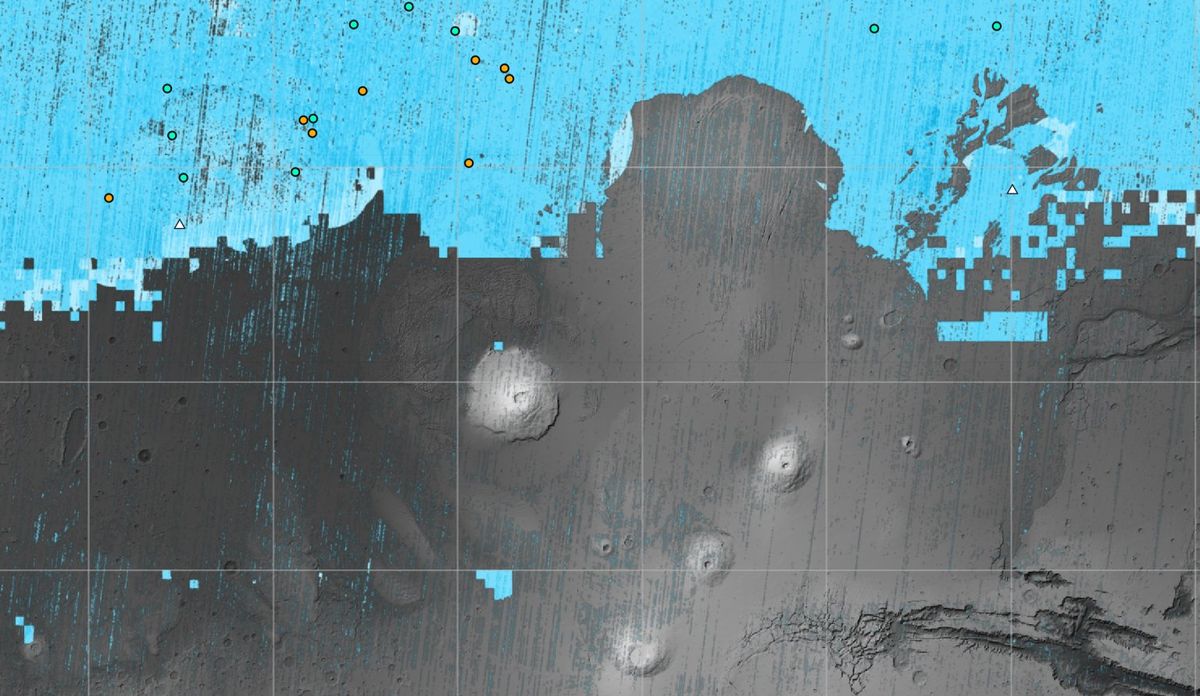

The NASA-funded Subsurface Water Ice Mapping (SWIM) project released its fourth and most recent map of where on Mars we might find, as you might expect, subsurface water ice. NASA officials say this map will help mission planners decide where on Mars to actually send the first humans to traverse the planet.

Since 2017, SWIM — led by the Planetary Science Institute and managed by NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory — has collated data from multiple NASA Mars missions in order to stitch together a map of how likely it is that a given part of Mars overlays water.

For their latest map, the scientists relied on data from the Context Camera (CTX) and High Resolution Imaging Experiment (HIRISE), both of which are aboard the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter. These instruments provide high-resolution imagery of the Martian terrain. For instance, they can identify tiny impact craters that are expected to have blown the Martian surface away to reveal “ice,” or so-called “polygon terrain,” where ice melting and refreezing (and melting and freezing again) with the march of the seasons etches cracks in the ground.

Related: Mars ice deposits could pave the way for human exploration

Knowing where Martian ice can be found is crucial for crewed mission planning, which will involve careful balancing act. Astronauts want to find water ice, for one, which will give them a valuable source of water so they won’t have to carry much of it from Earth. That might indicate the best landing zone falls near the Martian poles — but planners also don’t want to land astronauts where it’s too chilly. If it’s too cold, the crew will need to use extra amounts of valuable energy to keep themselves warm.

“If you send humans to Mars, you want to get them as close to the equator as you can,” Sydney Do, SWIM’s project manager, said in a statement. An ideal spot, then, would be a patch with as low a latitude as possible that still contains accessible ice. That’s where these Martian ice maps come in handy.

And even beyond mission planning, scientists believe they can use maps like SWIM’s to better understand why, exactly, Mars looks the way it does.

“The amount of water ice found in locations across the Martian mid-latitudes isn’t uniform; some regions seem to have more than others, and no one really knows why,” Nathaniel Putzig, SWIM’s co-lead at the Planetary Science Institute, said in the statement. “The newest SWIM map could lead to new hypotheses for why these variations happen.”

Dr. Thomas Hughes is a UK-based scientist and science communicator who makes complex topics accessible to readers. His articles explore breakthroughs in various scientific disciplines, from space exploration to cutting-edge research.