NASA’s Juno spacecraft has made a second flyby of Jupiter’s moon Io, capturing the solar system’s most volcanic body in stunning detail. The spacecraft also allowed operators to glimpse a side of Io not seen in 35 years.

The images of Io were taken last week, made possible by the Feb. 3 flyby that saw Juno dip to within 930 miles (1,500 kilometers) of the surface of the Jovian moon.

This close approach, which matched Juno’s last Io flyby on Dec. 30, 2023, in terms of distance, allowed the spacecraft’s JunoCam instrument to capture several volcanic features of the moon, including actively erupting plumes, lava lakes and tall mountain peaks and the shadow they cast on Juno’s surface.

One of the most impressive images captured by Juno was snapped on Feb. 4 at the tail end of the flyby and shows two plumes escaping from the volcanic moon. According to NASA, the plumes were seen as the spacecraft was at an altitude of 2393.5 miles (3,852 kilometers) over Io.

The image of the twin plumes, the source of which is not shown, is evidence of the ongoing volcanic activity of this Jovian moon.

Related: NASA’s Juno spacecraft will get its closest look yet at Jupiter’s moon Io on Dec. 30

Io is around the size of Earth’s moon, but unlike the moon, it is littered with hundreds of actively erupting volcanoes that are capable of blasting material dozens of miles into the thin, waterless atmosphere of this Jovian moon.

The source of Io’s extreme volcanism is believed to be the gravitational influence of its host planet, Jupiter, and that of its three other large Jovian moons — Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto — which torture the innermost Galilean moon, named because they were discovered by Italian astronomer Galileo Galilei.

This constant gravitational push and pull on Io generates tidal forces so intense that it can cause the surface of the moon to rise and fall by heights as great as 330 feet (100 meters), equivalent to the surface of Earth at New York suddenly jumping up above the Statue of Liberty. This also triggers extreme volcanism within Io.

Another image of Io captured just after the flyby, this time on Feb. 5, shows the Jovian moon looking positively psychedelic. The image was created with data from multiple filters, and shows Io’s dark left-hand side resplendent in greens and reds, while the illuminated right side takes on a suitably fiery orange hue.

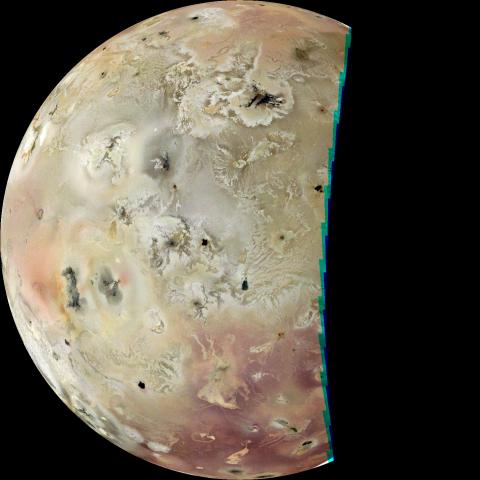

Another image snapped by JunoCam on Feb. 5 reveals the side of Io that permanently faces Jupiter, the ‘sub-Jovian hemisphere.’

NASA says this is the first time that the sub-Jovian hemisphere of Io has been seen since the Voyager 1 spacecraft flew through the Jovian system in 1979.

The sub-Jovian hemisphere is illuminated in this image thanks to light that bounces from Jupiter’s cloud tops. This illumination allowed JunoCam to pick out several surface changes on Io being driven by volcanic activity.

This includes a reshaping of the compound flow field at a region called Kanehekili in the center left of the image, which contains 2 persistent high-temperature hot spots and an active volcanic plume. To the east of Kanehekili, named after the Hawaiian god of thunder, Juno spotted a new lava flow.

The NASA spacecraft, now in the third year of its extended mission after its primary mission ended in July 2021, won’t come as close to Io as this again. Each subsequent flyby after Feb. 3 will see it approach the volcanic moon at increasing distances.

The next close approach will see Juno buzz at an altitude of about 10,250 miles (16,500 km), while the final flyby will bring the NASA spacecraft to within around 71,450 miles (115,000 kilometers) of the volcanic moon.

Juno’s extended mission investigating Jupiter and its moons is set to last until Sept. 2025, at which time NASA will intentionally crash the probe into the atmosphere of the gas giant.

Dr. Thomas Hughes is a UK-based scientist and science communicator who makes complex topics accessible to readers. His articles explore breakthroughs in various scientific disciplines, from space exploration to cutting-edge research.