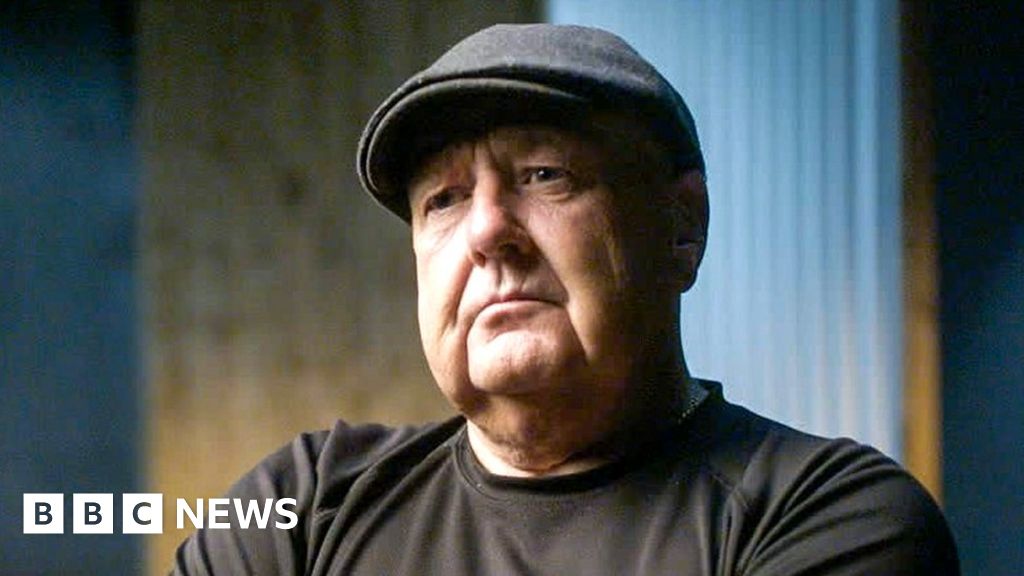

Image source, The Garden Productions Limited

Dave Roper says going on strike in 1984 was a last resort

Forty years on, a former coal miner on the front line in the 1984-85 miners’ strike reveals the painful choice he had to make when he lost his newborn son during what was arguably the UK’s most bitter industrial dispute.

“I’ve got a story to tell, and I think it’s important that some people hear it,” says Dave Roper.

In March 1984, the then-miner joined tens of thousands of colleagues from pits across the country in a strike against the planned closure of 20 collieries deemed uneconomic by the National Coal Board – a government agency.

For many of the men in the National Union of Mineworkers (NUM), the walkout left them and their families without wages for very nearly a year.

Roper lived near Rotherham in South Yorkshire.

“I worked at Silverwood Colliery, which were 800 yards from my door. I loved it, but it were dangerous,” he tells a new BBC Two documentary.

“We didn’t want to go on strike, nobody wanted to go on strike. It’s always a last resort isn’t it.”

When the strike began, Roper and his wife were expecting their second child

Roper was 29 at the time of the walkout, married with one child and another on the way, with “not a lot of money”, he says.

Like many strike families, they relied on support from the wider community.

“At [the] soup kitchen we used to get at least one good meal a day. But yeah it were quite difficult,” he says.

As the dispute raged on, with no wages or money saved, Roper’s wife went into labour in the summer of 1984.

“She said, ‘I don’t know what’s wrong with baby, they’ve [taken] it down to special care.'”

In August 1984, wives of miners from Kellingley Colliery in North Yorkshire prepared up to 400 meals daily for strikers’ families

Their son, Adam, had been born with complications and “physical deformities” says Roper, and passed away a week later. Roper was devastated.

“I got a form for a funeral grant. They sent a letter back saying, ‘Because you’re on strike, you’re not entitled to the funeral grant,'” he says. “I don’t even know how much a funeral would have been.”

As a striking miner, Roper was not eligible for financial assistance with the funeral expenses. This was a decision that was later reversed by the Department of Health and Social Security (DHSS) in October 1984 after growing pressure.

Roper contacted an undertaker and told him he didn’t have the money to pay for his son’s funeral.

“He said: ‘I’ll contact a relative of a dead person, and I’ll ask them if we can put the baby in the dead relative’s coffin with them,'” says Roper. “So I’ve got a free funeral. They paid for the funeral for the baby.”

“I said, ‘Oh, thank you. Tell them thank you,'” he recalls.

But pride stopped him and his wife from attending the ceremony in Rotherham.

“I’m going to somebody’s funeral and they’ll think ‘Why the bloody hell is he here?'” says Roper. “And the close people will think: ‘That’s them who can’t afford a funeral’.”

Image source, Getty Images

The strike divided communities and families, with some miners crossing picket lines – Lea Hall Colliery, Staffordshire, March 1984

Roper says if this happened today, the funeral costs could have been raised via other means, such as fundraising websites.

He is still angry at Margaret Thatcher’s Conservative government – in office at the time.

“They could have given me a loan,” he says in tears.

To bury a child in a coffin with an unrelated adult happened more frequently in the 19th Century – because of poverty and the higher rate of infant mortality.

The practice continued into the early 20th Century – with infants handed to funeral directors by families, midwives or doctors.

Public Health funerals are also provided by local authorities for members of the community who have no next of kin and no funeral arrangements in place, or whose relatives or friends are unable to pay for the funeral.

As he looks back after 40 years, Roper says the miners at the time were not just taking on the coal board, but also the state. But he says he has no regrets about joining the strike.

“I only have to take a look around my community and the communities in South Yorkshire to know I was 100% right.”

If you are affected by any of the issues raised in this story, support and advice is available via the BBC Action Line.

William Turner is a seasoned U.K. correspondent with a deep understanding of domestic affairs. With a passion for British politics and culture, he provides insightful analysis and comprehensive coverage of events within the United Kingdom.