- By Marianna Spring

- BBC disinformation and social media correspondent

“I never meant to hurt anyone” says Julia Wandelt

When Julia Wandelt posted on social media that she believed she was Madeleine McCann, she became a lightning rod for online anger. In the first of a new series of stories exploring extraordinary cases of online hate and the possibility of forgiveness, Julia reveals for the first time her motives and regrets.

As Julia Wandelt plays guitar to me in her bedroom in Poland, we’re surrounded by teddy bears. One is bright pink, wearing a T-shirt that reads: “You Got This!”

It was a gift, the 22-year-old says, from some of her new followers. She got to know them after creating an Instagram account called @iammadeleinemccan – referring to the British girl who went missing in Portugal in 2007 but missing the final “n” from her surname.

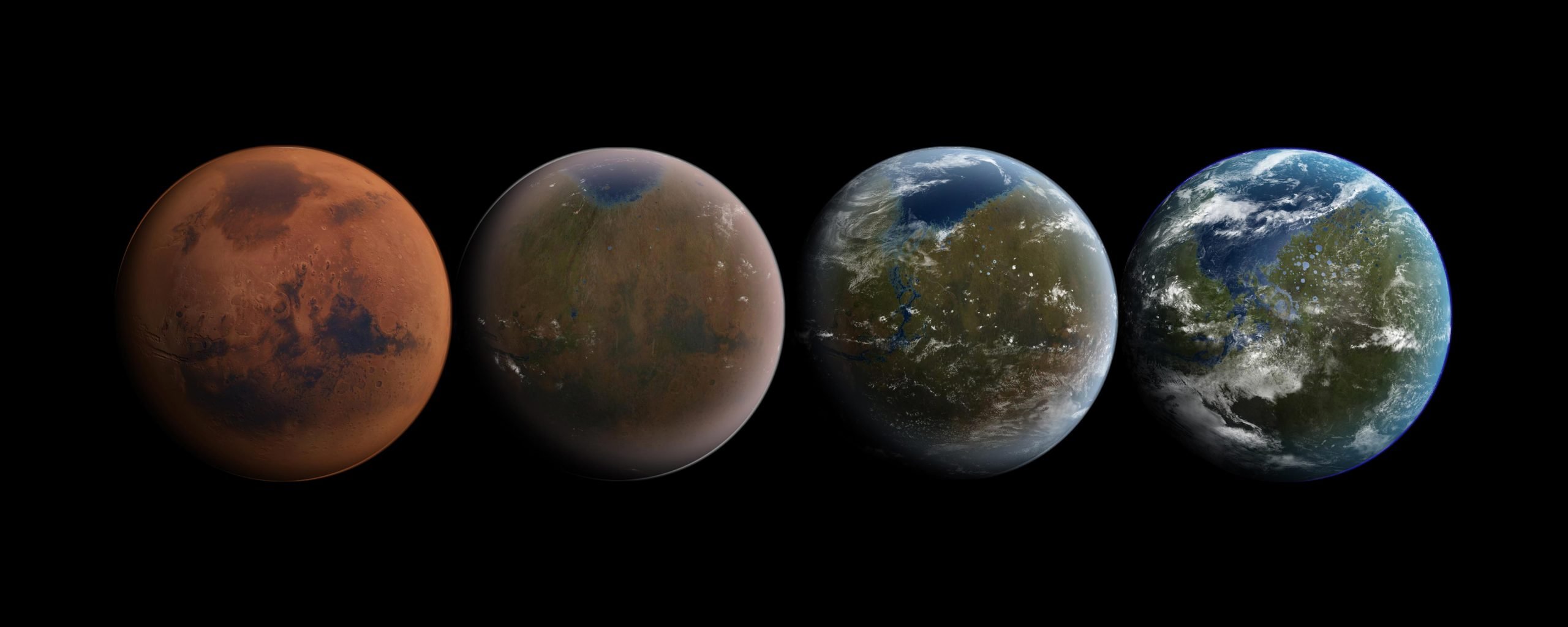

Madeleine McCann’s disappearance at the age of three – which remains unsolved – is one of the most widely reported in history. Online communities of obsessives have grown up around the case, and Julia’s account was like petrol thrown onto a fire already burning across social media sites like Instagram, TikTok and X.

“I never meant to hurt anyone – including [the] McCanns,” she told me. “I really wanted to know who I am.”

If she were to go back in time, Julia says she would never have made the Madeleine McCann profile.

“I would never go on social media. It can destroy you,” she explained.

Madeleine McCann’s disappearance is still unsolved, and online communities of obsessives have sprung up around it

I’m starting with Julia, because her case seemed to be one of the most extraordinary I’d spotted.

The original account she posted on as Madeleine at the start of 2023 no longer exists. But among the online groups of Madeleine McCann obsessives was one dedicated to analysing Julia’s social media posts, which is where I found her personal account.

After I messaged her, Julia told me she wanted to share her side of the story. Because she has spoken openly about her past struggles with her mental health, we chatted multiple times on the phone over several weeks, as well as meeting in person – so we could be confident she was making an informed decision about speaking out.

We first met at her flat in Poland. As I arrived, I was greeted by a loud meow from Julia’s cat Monty. Now, rather than posting about the Madeleine McCann case, Julia shares videos of him doing tricks.

So, who exactly is Julia? And why did she post on social media that she was Madeleine? Julia says what happened had its roots in a traumatic childhood.

She says she was isolated at school and that as a young child she was sexually abused.

Music became her escape, she says. From time to time as we talk, she picks up her guitar and sings an improvised song. “It’s still the way to deal with difficulties in my life,” Julia says.

Later, aged about 20, she was in therapy and started to realise her memories from childhood were patchy – with chunks of time where she couldn’t remember much at all.

Psychiatrists and psychologists I’ve spoken to say it’s common to experience memory loss if you’ve been abused. It’s the brain’s way of protecting us, they say.

Julia started to wonder if the blanks in her memory might hide a big secret – that maybe she had been adopted. She began to ask her relatives to help fill in the gaps.

“For example, can you show me some pictures from childhood? Can you show me your pregnancy photos?” Julia says.

Julia says she has gaps in her memory of childhood after suffering abuse – which led her to wonder if they hid a big secret

She says her family dismissed her concerns that she might be adopted, and wouldn’t answer her questions. That only served to fuel her suspicions.

Julia began to wonder whether there was an even more disturbing reason for their defensiveness. Could she have been kidnapped?

Frustrated by her family’s silence, Julia turned to the internet for answers. She started googling missing persons websites from her bedroom.

That was when she found Madeleine’s case. Julia told me she had never heard of her disappearance before, since it had not been such a big news story in Poland.

On the profiles of missing people there are sometimes sketches or e-fits of potential suspects – and Julia thought she recognised one of the men on Madeleine’s profile.

“I know [what] my abuser looks like. And I know this is very, very similar to the suspects from [the] Madeleine McCann page.”

Julia’s mind went into overdrive. Given Julia now suspected she may not belong in her family, this felt like the answer she had been looking for. And when she noticed an unusual physical resemblance between her and Madeleine, it seemed to confirm she was right.

Both Julia and Madeleine have a coloboma of the iris – a rare eye abnormality that affects one in every 10,000 babies. It’s a gap in the iris that can make the pupil look keyhole-shaped. Sitting opposite her, I could see this was the case.

So Julia contacted the police in Poland and the UK. “I called them so many times,” she tells me. “But no-one treated me seriously.”

On a now-deleted Instagram account, Julia posted images of herself as a child alongside pictures of Madeleine

Over the years, several young women and girls have come forward claiming to have been Madeleine McCann, but all have proven to be false.

Julia didn’t feel listened to by anyone, so she says she turned to social media to see if people would pay attention there.

She was very open with her followers, telling them she had been abused as a child, her struggles with depression and difficulties in coping with the attention she had unleashed.

“I was looking at what people write, what they say, if they believe me or if they will ignore me,” she said.

Almost immediately Julia was engulfed by a whole new community online who offered support, validation and even gifts – flowers, bracelets, teddies and blankets – one for her and one for her cat.

A girl with few friends at school had become a young woman who very quickly gathered more than a million followers on her Instagram profile.

“I’ve never felt the people who support me or who follow me are fans. I always feel that they are just people who are friends,” she told me.

But social media notoriety also brought criticism and abuse.

“I knew that there will be people who will not believe me or hate me, but I didn’t expect that I will get death threats, for example. It was something that I don’t understand. People knew that I was abused and they all knew that I deal with depression,” Julia says.

“I was trying to be strong even when people said, you should die. You should be raped. You should be killed. You should be murdered. You shouldn’t exist in this world. You’re a bitch.”

One of the BBC’s most trolled journalists, Marianna Spring, dives into her inbox and investigates extraordinary cases of online hate. She meets the people at the heart of these conflicts, and in some cases brings them together, to see if understanding – even forgiveness – is ever possible.

One person said she had put a bounty on Julia’s head – and offered €30,000 (£25,700) as a reward.

Nonetheless, Julia kept posting. Why?

“I wanted to know the truth. Some people said [I wanted] to be a star. ‘She wants to make her music go viral, blah, blah’,” she explained. But she says she never posted her music on her new Madeleine McCann Instagram, and that wasn’t her aim.

By March last year, Julia’s story had gone global. It attracted the attention of producers in the United States and she was invited to go on the long-running chat show hosted by psychologist Dr Phil.

About that time, Julia decided to take a DNA test. She says neither her parents nor the McCanns agreed to provide DNA samples for Julia’s to be compared against. But when the results arrived, they showed that Julia was from Poland, with some Lithuanian and Romanian heritage. In other words, she is not Madeleine McCann.

Her family said at the time in a statement: ”For us as a family it is obvious that Julia is our daughter, granddaughter, sister, niece, cousin and step-niece. We have memories, we have pictures. We always tried to understand all the situations that happened with Julia.”

While some followers turned on her after the results of the DNA test came in, others remained in close contact with her and offered her support. They didn’t abandon her – and several continued to follow her for being Julia.

Julia says she posted an apology to the McCanns because she was worried she might have added to their distress.

Police in Portugal, the UK and Germany continue to investigate the disappearance

“I apologised to the McCanns because I don’t know them personally. I don’t know if they were watching this journey, if they were sad or whatever. And I just wanted to say sorry. Because every person can react in a different way and maybe it brought them more sadness,” Julia says.

“I didn’t want them to feel sad.”

How much did she think about what they had been going through, as parents of a missing child?

“I really wanted to know who I am, and I knew that it could make them feel sad.”

But she says she believed at the time that she might be able to help them find their child.

In light of all that, is understanding – and forgiveness – possible here?

Given how extreme and never-ending the social media conversation has been about this case, anything Madeleine’s parents say is likely to trigger more hate and headlines. There’s also an active police investigation into Madeleine’s disappearance that they are wary not to disrupt.

Kate and Gerry McCann do not use social media, which their supporters say shields them from some of the trolling

But I reached out to the Find Madeleine campaign, her family’s official search organisation, and people connected to the McCanns.

Those people, who have also been affected by some of Julia’s content, told me they are all willing to accept Julia’s apology and forgive her for the situation that unfolded online.

According to the Find Madeleine campaign, Kate and Gerry McCann do not use social media, which somewhat shields them from the trolling.

Julia is now at peace with a lot of what has unfolded – the consequences of her own actions and the horrible abuse she received. In a strange way, she says it has helped her.

She is aware that speaking out could trigger more abuse – but for her, it is important to tell her side of the story in her own words.

I got in touch with Instagram, X and Tiktok and none of them responded with a comment about the case. All of the social media sites say publicly they have policies in place to protect users from hate and disinformation.

When Julia first began questioning her identity, she says she was depressed and “felt that I don’t belong here”. Now she tells me: “I realise that I am strong and I am a fighter and I’m not a weak person.”

Julia turned to social media for community, validation and answers. The online world can be a quick and easy place to find an intense sense of belonging.

But on social media, communities define themselves in opposition to one another and this can trigger hate.

Offline, though, people seem more open to nuance – fairness, tolerance and kindness.

Those qualities are what really make us human.

Emily Foster is a globe-trotting journalist based in the UK. Her articles offer readers a global perspective on international events, exploring complex geopolitical issues and providing a nuanced view of the world’s most pressing challenges.