By

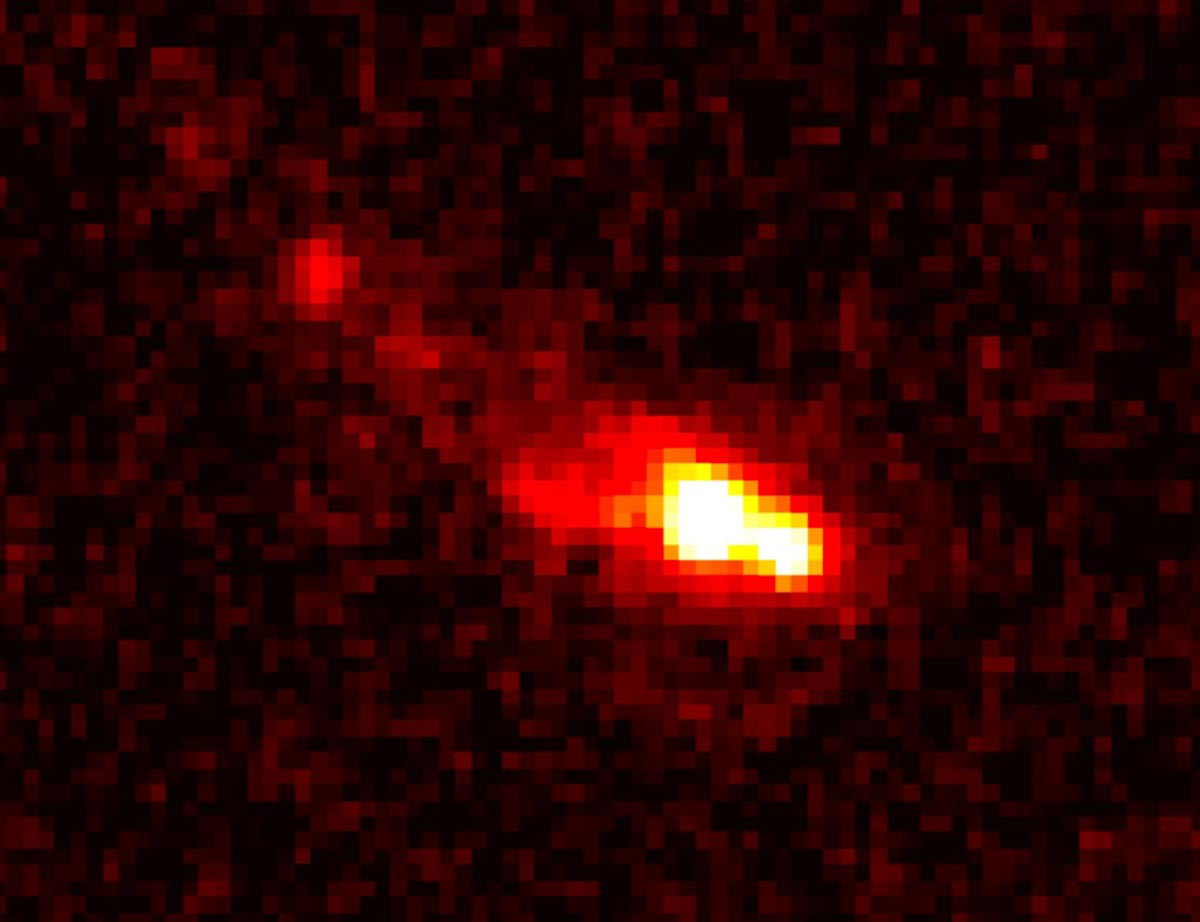

JWST shows details of a massive galaxy merger 13 billion years ago (insert of another early galaxy shows the significance of the new JWST images). Credit: ASTRO 3D

Groundbreaking observations by the James Webb Space Telescope of an early galaxy merger indicate faster and more efficient star formation than previously understood, revealing complex stellar populations and challenging current cosmological theories.

- Galaxies and stars developed faster after the Big Bang than expected.

- Detailed pictures of one of the very first galaxies show growth was much faster than we thought.

An international research team has made unprecedentedly detailed observations of the earliest merger of galaxies ever witnessed. They suggest stars developed much faster and more efficiently than we thought.

They used the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) to observe the massive object as it was 510 million years after the Big Bang – i.e. around 13 billion years ago.

“When we conducted these observations, this galaxy was ten times more massive than any other galaxy found that early in the Universe,” says Dr. Kit Boyett, an ASTRO 3D Research Fellow on First Galaxies, from the University of Melbourne. He is lead author on a paper published recently in Nature Astronomy. The paper has 27 authors from 19 institutions in Australia, Thailand, Italy, the USA, Japan, Denmark and China.

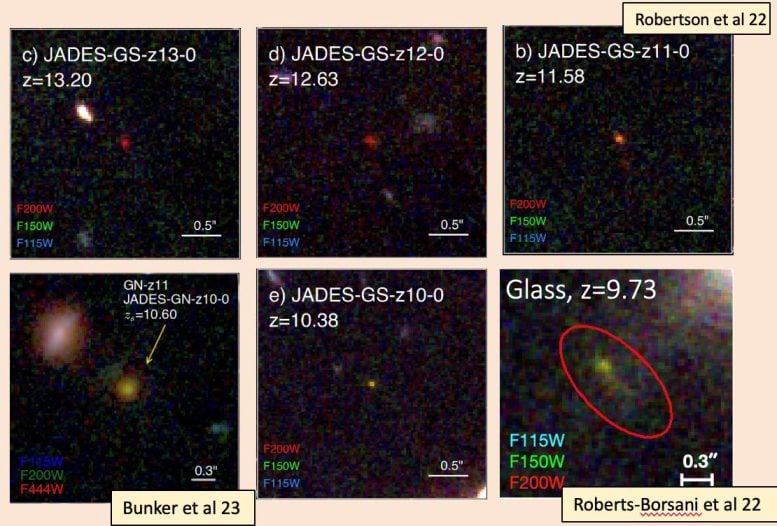

JWST, launched in 2021, is enabling astronomers to see the early Universe in ways that were previously impossible. Objects that appeared as single points of light through earlier telescopes such as the Hubble Space Telescope, are revealing their complexity.

JWST shows details of massive galaxy merger 13 billion years ago. Credit: ASTRO 3D

“It is amazing to see the power of JWST to provide a detailed view of galaxies at the edge of the observable Universe and therefore back in time,” says Prof. Michele Trenti, ASTRO 3D First Galaxies theme leader and University of Melbourne node leader. “This space observatory is transforming our understanding of early galaxy formation” adds Prof. Trenti.

The observations in the current paper show a galaxy consisting of several groups with two components in the main group and a long tail, suggesting an ongoing merger of two galaxies into a larger one.

“The merger hasn’t finished yet. We can tell this by the fact we still see two components. The long tail is likely produced by some of the matter being cast aside during the merger. When two things merge, they sort of throw away some of the matter. So, this tells us that there’s a merger and this is the most distant merger ever seen,” says Dr. Boyett.

This and other observations using the JWST are causing astrophysicists to adjust their modeling of the early years of the Universe.

“With James Webb, we are seeing more objects in the early cosmos than we expect to see, and those objects are more massive than we thought as well,” says Dr. Boyett. “Our cosmology isn’t necessarily wrong, but our understanding of how quickly galaxies formed probably is, because they are more massive than we ever believed could be possible.”

Other ancient galaxies. Credit: ASTRO 3D

Dr. Boyett’s team’s findings show these galaxies were able to accumulate mass so fast by merging.

But it is not only the size of the galaxies and the speed with which they grew that surprises Dr. Boyett. His paper for the first time describes the population of stars that make up the merging galaxies – another detail made possible by JWST.

“When we compared our spectrum analysis with our imaging, we found two different things. The image told us the population of stars was young, but the spectroscopy spoke of stars that are quite old. But it turns out both are correct because we don’t have one population of stars but two,” Boyett says.

“The old population has been there for a long time and what we believe happens is the merger of the galaxies produces new stars and that’s what we’re seeing in the imaging – new stars on top of the old population.”

Most studies of these very distant objects show very young stars, but this is because the younger stars are brighter and so their light dominates the imaging data. The JWST, however, allows for such detailed observations the two populations can be distinguished.

“It’s the fact that the spectroscopy is so detailed, we can see the subtle features of the old stars that tell us actually there’s more there than you think,” says Dr. Boyett.

“This is not all that surprising, we know that over the history of a universe there are peaks of new star formation for various reasons, and that results in multiple populations.

“But it’s the first time we’ve really seen them at this distance.”

The paper has significant implications for current modeling.

“Our simulations can produce an object similar to the one we observed, roughly at the same age of a universe, and roughly the same mass, however, it’s incredibly rare. So rare there’s only one of these in the whole model. The chance of us observing that with our observations, then suggest we either incredibly lucky or our simulations are wrong, and this sort of object is more common than we think,” says Dr. Boyett.

“The thing we think we’re missing is that stars were forming much more efficiently and that may be what we need to change in our models.”

Reference: “A massive interacting galaxy 510 million years after the Big Bang” by Kristan Boyett, Michele Trenti, Nicha Leethochawalit, Antonello Calabró, Benjamin Metha, Guido Roberts-Borsani, Nicoló Dalmasso, Lilan Yang, Paola Santini, Tommaso Treu, Tucker Jones, Alaina Henry, Charlotte A. Mason, Takahiro Morishita, Themiya Nanayakkara, Namrata Roy, Xin Wang, Adriano Fontana, Emiliano Merlin, Marco Castellano, Diego Paris, Maruša Bradač, Matt Malkan, Danilo Marchesini, Sara Mascia, Karl Glazebrook, Laura Pentericci, Eros Vanzella and Benedetta Vulcani, 7 March 2024, Nature Astronomy.

DOI: 10.1038/s41550-024-02218-7

Dr. Thomas Hughes is a UK-based scientist and science communicator who makes complex topics accessible to readers. His articles explore breakthroughs in various scientific disciplines, from space exploration to cutting-edge research.