People predicting the end of world generally make those predictions without scientific evidence to support them. So when an animal-behavior researcher ran experiments in the 1960s that described “utopian” rodent societies pushing themselves into extinction, scientists and the general public alike took notice. That attention never fully went away.

Ever since the original “Universe 25” rodent utopia experiment took place, countless people have discussed the study and its findings, with some suggesting it could be an apocalyptic prediction for the future of humanity. The story pops up online every so often, and Snopes readers have written many emails over the past few years asking us about the notorious rodent utopia experiment.

The Background

Before explaining the experiment, it’s important to understand why it was performed. While environmentalism as a political theory had been around in bits and pieces since the early days of the Industrial Revolution, it was not until just after World War II that people truly began to politically organize around the environment.

One of the largest fears at the time was overpopulation — sometimes called Malthusianism after an 18th-century demographer, Thomas Malthus, who proposed that population would eventually grow faster than food production, meaning that, eventually, humanity would be unable to feed everyone. Many early environmentalists proposed similar ideas.

In the 1950s, an animal behaviorist named John Calhoun started working at the National Institute of Mental Health. He had long worked with rats, the subject of his Ph.D. thesis, and was interested in studying how a rat society would develop over time when it was limited only by space. In other words, he wanted to test the effects of overpopulation.

In order to run his experiment, Calhoun designed complexes, which he named “Universes,” that would provide his rodent subjects all they needed to survive — food, water and protection from predators and disease. The only thing that would limit the population growth would be space.

As he watched the rodent societies grow, he began noticing strange trends:

Pregnant females began having problems raising offspring. Dominant males became incredibly territorial and overactive, while subordinate males increasingly withdrew from the larger group, coming out “to eat, drink and move about only when other members of the community were asleep.” Rats became so conditioned to eating with others that they would refuse to eat alone. Some males became hypersexual and attempted to mate with anyone and everyone. Fighting was frequent. Rats began cannibalizing other rats. At one point, the infant mortality rate reached an astonishing 96%.

As one of Calhoun’s assistants put it, “utopia” had turned into a “hell.”

The Experiments

Calhoun published the results of his early experiments in the February 1962 edition of Scientific American, with the title “Population Density and Social Pathology,” coining the term “behavioral sink” to describe the most-crowded spots, where he observed the highest rate of antisocial behavior. In the 1960s, at the height of political discourse about so-called “social decay” in American cities, the study was a natural discussion topic. In the meantime, Calhoun continued his work.

And now we arrive the 25th version of this study Calhoun ran, and the one he would become most well-known for: Universe 25. It was the only one of Calhoun’s habitats fully studied from beginning to end. Universe 25 was populated with mice instead of rats, but most everything else remained the same. Mice had everything they needed to survive and were limited only by space.

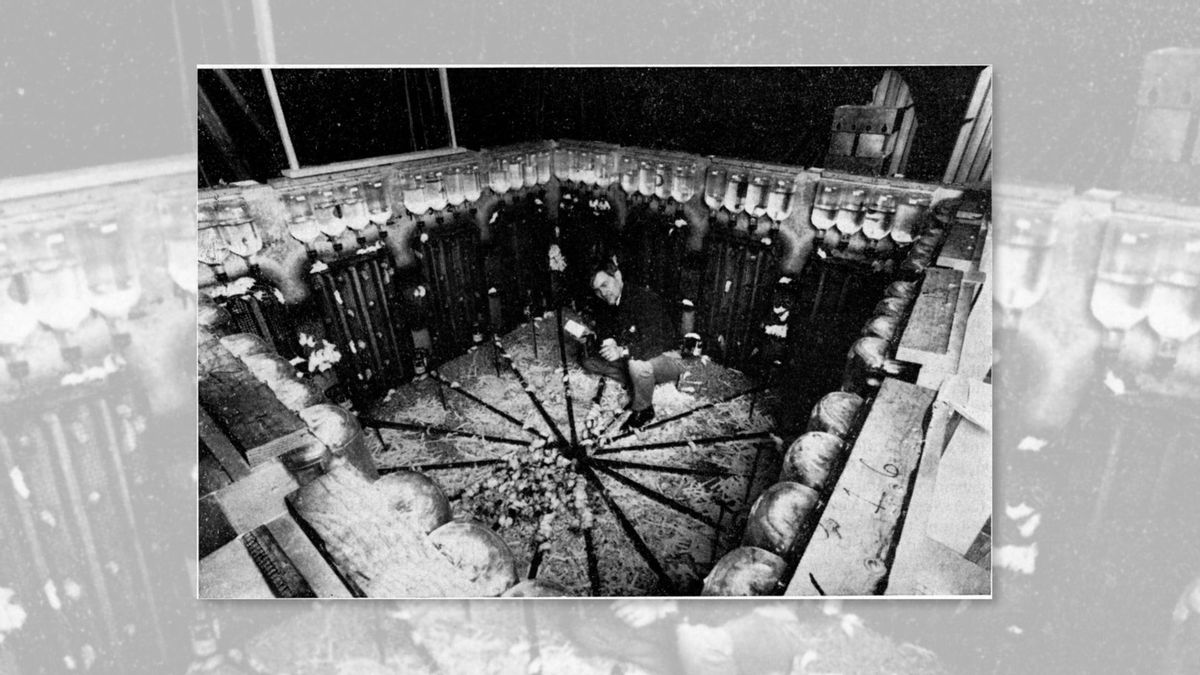

Calhoun constructed a square box with a side length of 54 inches. He built nesting boxes, water bottles and food hoppers into the walls, with each side of the universe having 64 different nesting boxes located at various heights, 16 water bottles and four food hoppers. All of the “utilities” were accessible via a series of mesh tunnels running from the floor up the side of the wall.

Calhoun published the results of Universe 25 in 1973 in a paper called “Death Squared: The Explosive Growth and Demise of a Mouse Population.” He broke down the development and collapse of the society into four phases:

- Phase A, consisting of the first 104 days, was the adjustment phase, with “considerable social turmoil” between the eight original mice placed into the habitat. Phase A ended once the mice had their first offspring.

- Phase B, which Calhoun named the resource exploitation phase, lasted from Day 105 to Day 315. During this phase, the population grew rapidly, reaching more than 600 mice before growth began slowing. Social stratification also began to happen, with different groups of mice living in certain areas and self-selecting into their own independent groups.

- Phase C, called the stagnation phase, lasted from Day 316 to Day 560. Male mice who were not able to find room in the pre-existing social structure began to withdraw from society, violently attacking one another. Their female counterparts retreated into the highest boxes, also isolating themselves. Socially dominant males began to lose control over their territory, leaving mothers to aggressively defend their young, sometimes even abandoning them. “For all practical purposes there had been a death of societal organization by the end of Phase C,” Calhoun wrote.

- Phase D was the death phase. The death rate outpaced the birth rate, and the society began to shrink. Mothers raised newborn mice for a very short time, and Calhoun proposed that the young generation’s strange behaviors were a direct result of a very abnormal social upbringing that did not allow some of the more “complex behaviors,” including mating rituals, to develop. Females rarely gave birth, and a large group of males, which Calhoun named the “beautiful ones,” did nothing other than eat, drink, sleep and groom themselves. During Phase D, a few mice were placed in newly established universes to see whether they would relearn those social behaviors. They did not.

Calhoun’s 1973 paper was not subtle. “I shall largely speak of mice, but my thoughts are on man, on healing, on life and its evolution,” he wrote. He made frequent references to the Book of Revelation in the Bible and almost all of his wording aimed to personify his rodent subjects. The mice in Universe 25 lived in “walk-up apartments,” and Calhoun described subgroups like “somnambulists” or the “bar flies,” terms that could easily be mapped to urban life.

The conclusions felt grim, and the fears of overpopulation made their way into pop culture, like the movie “Soylent Green.” There’s even a book for children very loosely based around Calhoun’s mouse cities (although without the doom and gloom of societal breakdown): “Mrs. Frisby and the Rats of NIMH.”

The Conclusions

In modern times, Calhoun’s Universe 25 experiment is often used as a way to talk about some kind of “degradation of Western society.” These analyses look at Calhoun’s experiments and say, “He predicted this would happen to humans, and look at all the cultural degeneracy we see today!” For instance, here’s an excerpt from a comment about the experiment we’ve seen repeatedly on Facebook:

According to Calhoun, the death phase consisted of two stages: the “first death” and “second death.” The former was characterized by the loss of purpose in life beyond mere existence — no desire to mate, raise young or establish a role within society. As time went on, juvenile mortality reached 100% and reproduction reached zero. Among the endangered mice, homosexuality was observed and, at the same time, cannibalism increased, despite the fact that there was plenty of food. Two years after the start of the experiment, the last baby of the colony was born. By 1973, he had killed the last mouse in the Universe 25. John Calhoun repeated the same experiment 25 more times, and each time the result was the same. Calhoun’s scientific work has been used as a model for interpreting social collapse, and his research serves as a focal point for the study of urban sociology. We are currently witnessing direct parallels in today’s society … weak, feminized men with little to no skills and no protection instincts, and overly agitated and aggressive females with no maternal instincts.

Scientists have repeatedly pushed back against these ideas since Calhoun’s research came out. Researchers who attempted to replicate Calhoun’s studies in humans found mixed results, and other scientists chastised him for extrapolating rodent behavior to humans. While the popular conception of Universe 25 focused on the apocalyptic death of society because of overpopulation, other psychologists suggested otherwise.

In an 2008 interview with the NIH Record, Dr. Edmund Ramsden, a science historian, explained the results of a similar 1975 experiment by a psychologist Jonathan Freedman:

Freedman’s work, Ramsden noted, suggested that density was no longer a primary explanatory variable for society’s ruin. A distinction was drawn between animals and humans.

“Rats may suffer from crowding; human beings can cope… Calhoun’s research was seen not only as questionable, but also as dangerous.”

Freedman suggested a different conclusion, though. Moral decay resulted “not from density, but from excessive social interaction,” Ramsden explained. “Not all of Calhoun’s rats had gone berserk. Those who managed to control space led relatively normal lives.” Striking the right balance between privacy and community, Freedman argued, would reduce social pathology. It was the unwanted unavoidable social interaction that drove even fairly social creatures mad, he believed.

But what the modern critics often carelessly and conveniently leave out is how Calhoun’s research evolved after Universe 25: Up until his death in 1995, Calhoun looked for solutions to the problem he had discovered, altering his designs and controls to try to avoid the societal collapse of Universe 25. He described rodents coming up with creative solutions to daily tasks. And it was in this way that his experiments have actually proven more useful. Architects and urban designers have taken Calhoun’s experiments into consideration when designing buildings and cities. Prison researchers and reformers have also found Calhoun’s studies surprisingly helpful.

So yes, while Universe 25 and Calhoun’s “rodent utopias” were real experiments, they’re not the apocalyptic predictions that some people make them out to be.

Sources

Arnason, Gardar. “The Emergence and Development of Animal Research Ethics: A Review with a Focus on Nonhuman Primates.” Science and Engineering Ethics, vol. 26, no. 4, 2020, pp. 2277–93. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11948-020-00219-z.

Britannica Money. 18 Mar. 2024, https://www.britannica.com/money/Malthusianism.

Calhoun, John B. “Death Squared: The Explosive Growth and Demise of a Mouse Population.” Proceedings of the Royal Society of Medicine, vol. 66, no. 1P2, Jan. 1973, pp. 80–88. DOI.org (Crossref), https://doi.org/10.1177/00359157730661P202.

Calhoun, John B. “Population Density and Social Pathology.” California Medicine, vol. 113, no. 5, Nov. 1970, p. 54. PubMed Central, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1501789/.

—. “Space and the Strategy of Life.” Behavior and Environment: The Use of Space by Animals and Men, edited by Aristide Henri Esser, Springer US, 1971, pp. 329–87. Springer Link, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4684-1893-4_25.

Edmund Ramsden and Jon Adams. “Escaping the Laboratory: The Rodent Experiments of John B. Calhoun & Their Cultural Influence.” Journal of Social History, vol. 42, no. 3, 2009, pp. 761–92. DOI.org (Crossref), https://doi.org/10.1353/jsh.0.0156.

Environmentalism | Ideology, History, & Types | Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/topic/environmentalism. Accessed 17 May 2024.

Fredrik Knudsen. The Mouse Utopia Experiments | Down the Rabbit Hole. 2017. YouTube, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NgGLFozNM2o.

Garnett, Carla. “Medical Historian Examines NIMH Experiments In Crowding.” NIH Record, Vol. LX, No. 15, 25 July 2008, https://nihrecord.nih.gov/sites/recordNIH/files/pdf/2008/NIH-Record-2008-07-25.pdf.

Magazine, Smithsonian, and Maris Fessenden. “How 1960s Mouse Utopias Led to Grim Predictions for Future of Humanity.” Smithsonian Magazine, https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/how-mouse-utopias-1960s-led-grim-predictions-humans-180954423/. Accessed 17 May 2024.

Magazine, Smithsonian, and Charles C. Mann. “The Book That Incited a Worldwide Fear of Overpopulation.” Smithsonian Magazine, https://www.smithsonianmag.com/innovation/book-incited-worldwide-fear-overpopulation-180967499/. Accessed 17 May 2024.

Paulus, Paul. Prisons Crowding: A Psychological Perspective. Springer Science & Business Media, 2012.

Ramsden, Edmund. “The Urban Animal: Population Density and Social Pathology in Rodents and Humans.” Bulletin of the World Health Organization, vol. 87, no. 2, Feb. 2009, p. 82. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.2471/BLT.09.062836.

The Calhoun Rodent Experiments: The Real-Life Rats of NIMH. https://cosmosmagazine.com/science/mathematics/calhoun-rodent-experiments/. Accessed 17 May 2024.

“Universe 25, 1968–1973.” The Scientist Magazine®, https://www.the-scientist.com/universe-25-1968-1973-69941. Accessed 17 May 2024.

Woodstream, Woodstream. What Humans Can Learn from Calhoun’s Rodent Utopia. https://www.victorpest.com/articles/what-humans-can-learn-from-calhouns-rodent-utopia. Accessed 17 May 2024.

Dr. Thomas Hughes is a UK-based scientist and science communicator who makes complex topics accessible to readers. His articles explore breakthroughs in various scientific disciplines, from space exploration to cutting-edge research.