Down on the ground, death equals stillness – but not in space. Abandoned satellites are prone to tumble in unpredictable ways and an ESA project with the Astronomical Institute of the University of Bern sought to better understand this behaviour.

ESA’s Clean Space initiative has plans to remove dead satellites from highly trafficked orbits. The preferred method of ‘Active Debris Removal’ involves grabbing the target object, in which case knowledge of its precise orientation and motion will be vital. So the need is clear to understand the tumbling that almost all satellites and rocket bodies undergo after their mission end-of-life.

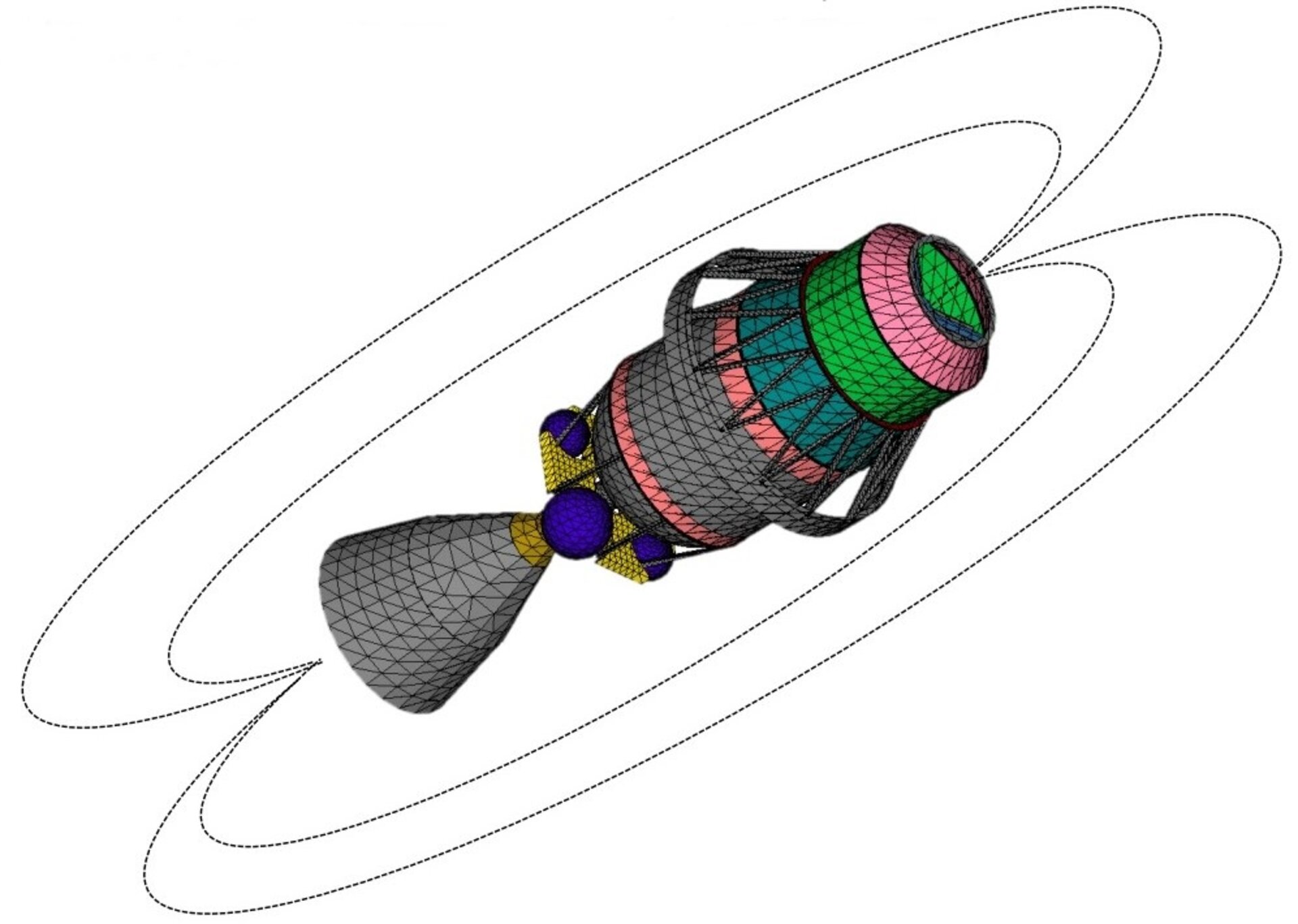

The project combined optical, laser ranging and radar observations to refine an existing ‘In-Orbit Tumbling Analysis’ computer model, aiming to identify, understand and predict the attitude motion of a fully defunct satellite within a few passes. More than 20 objects were observed during a two-year campaign.

The long list of perturbation triggers includes ‘eddy currents’ as internal magnetic fields interact with Earth’s magnetosphere, drag from the vestigial atmosphere, gravity gradients between the top of an object and its bottom, outgassing and fuel leaks, the faint but steady push of sunlight – known as ‘solar radiation pressure’ – micrometeoroid and debris impacts, even the sloshing of leftover fuel.

Among the study findings was rocket bodies and satellites in lower orbits are mostly influenced by gravity gradients and eddy currents, while up at geostationary altitudes, satellites with large solar panels are sensitive to solar radiation pressure.

The project was supported through ESA’s General Support Technology Programme, developing promising technologies for space.

Find out more here.

Dr. Thomas Hughes is a UK-based scientist and science communicator who makes complex topics accessible to readers. His articles explore breakthroughs in various scientific disciplines, from space exploration to cutting-edge research.