Something serendipitous happened in early November. It had to do with NASA’s Lucy spacecraft, a solar-winged probe currently on its way to investigate a trove of ancient asteroids locked in Jupiter‘s orbit around the sun. They’re called the Trojans, and they’re believed to be leftover blocks from the box that built our solar system.

But we’re not talking about the mighty Trojans right now. We’re talking about a little space object named Selam.

Here is Selam’s story.

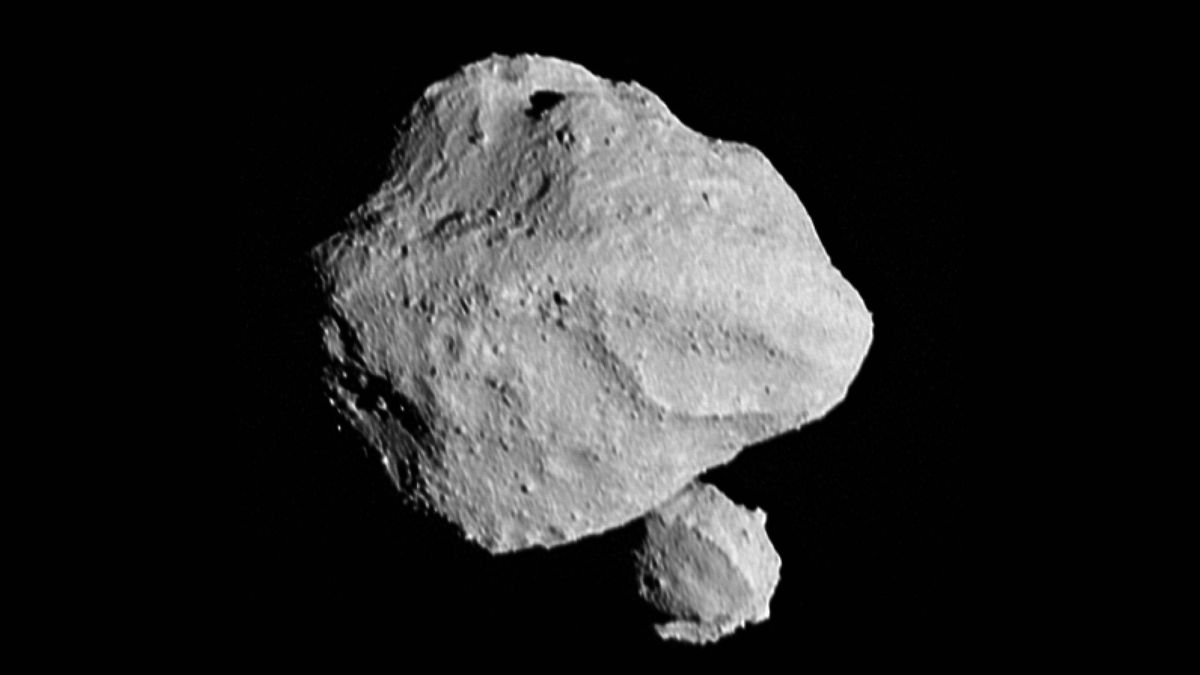

On Nov. 1, Lucy flew by one of its non-Trojan targets; you can think of these like stepping stones (stepping asteroids, rather) on the mission’s grander path. Asteroid number one’s name is Dinkinesh, or as scientists adorably call it, “Dinky.” Soon after, however, on Nov. 2, the Lucy team announced a surprise. Dinkinesh isn’t just one, but rather a binary system of two asteroids! In other words, Dinky had its very own moon. The scientists were thrilled. Little did they know, Dinky was about to surprise us once more.

Related: Strange moon of asteroid Dinkinesh is weirder than thought after NASA probe finds ‘contact binary’

On Nov. 7, to everyone’s shock, the team revealed that Dinky’s newfound satellite itself had a newfound satellite. In particular, the team said, the original satellite was a “contact-binary,” meaning it was two objects, a moon and a meta-moon, that were touching. This marked the first discovery of a contact-binary orbiting an asteroid.

“It is puzzling, to say the least,” the Southwest Research Institute’s Hal Levison, principal investigator for Lucy, said in a statement at the time. “I would have never expected a system that looks like this. In particular, I don’t understand why the two components of the satellite have similar sizes. This is going to be fun for the scientific community to figure out.”

All that was left? A name.

So, on Nov. 29, the Lucy team confirmed that we finally have a name for Dinky’s little contact-binary friend: Selam.

“Dinkinesh is the Ethiopian name for the fossil nicknamed ‘Lucy,'” Raphael Marshall of the Observatoire de la Côte d’Azur in France, who originally identified Dinkinesh as a potential target of the Lucy mission, said in a statement. “It seemed appropriate to name its satellite in honor of another fossil that is sometimes called Lucy’s baby.”

The fossil Selam, NASA explains, was discovered by Zeresenay Alemseged in 2000 in Dikika, Ethiopia. It’s believed to have belonged to a 3-year-old girl of the same species as Lucy, one of the first hominin fossils to become a household name as the Natural History Museum says. Selam, however, is thought to have lived more than 100,000 years before Lucy. Wonderfully, Selam translates from Ethiopian language Amharic to “peace,” while Dinkinesh translates to “you are marvelous.”

“Dinkinesh really did live up to its name; this is marvelous,” Levison had said at the time of its moon’s discovery.

Now, the team intends to study both Dinkinesh and Selam in greater detail to understand precisely how this asteroid-ception arose in the first place. Thanks to Lucy’s onboard instruments such as the high-resolution L’LORRI camera and Terminal Tracking Cameras, there’s probably a solid amount of information to go on.

“To assemble the final images, we must carefully account for the motion of the spacecraft, but Lucy’s accurate pointing information makes this possible,” said Amy Simon of NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, Greenbelt, Maryland. “These images will help scientists understand the composition of the asteroids, allowing the team to compare the makeup of the Dinkinesh and Selam and to understand how these bodies may be compositionally linked to other asteroids.”

It’s incredible that space rock stop number one on Lucy’s journey since launching in 2021 has yielded such interesting results — one can only imagine what’s in store for the rest of its 12-year excursion.

Dr. Thomas Hughes is a UK-based scientist and science communicator who makes complex topics accessible to readers. His articles explore breakthroughs in various scientific disciplines, from space exploration to cutting-edge research.