-

China’s Tiangong space station orbits nearly 240 miles (380 kilometers) above Earth.

-

China’s Tiangong space station orbits nearly 240 miles (380 kilometers) above Earth.

-

China’s Tiangong space station orbits nearly 240 miles (380 kilometers) above Earth.

China released new pictures of its Tiangong space station Tuesday as Chinese astronauts and space officials made a public relations visit to Hong Kong. These images, taken about a month ago, show the Tiangong complex in its fully assembled configuration with three modules staffed by three crew members.

A departing crew of three astronauts captured the new panoramic views of the Tiangong station in low-Earth orbit October 30, shortly after departing the outpost to head for Earth at the end of a six-month mission. These are the first views showing the Tiangong station after China completed assembling its three main modules last year.

The Tianhe core module is at the center of the complex. It launched in April 2021 with crew accommodations and life support systems for astronauts. Two experiment modules, named Wentian and Mengtian, launched in 2022. The first team of Chinese astronauts arrived at the station in June 2021, and Tiangong has been permanently staffed by rotating three-person crews since June 2022.

One of these crews closed out their six-month stint on the Tiangong station October 30. Their Shenzhou 16 ferry ship backed away from Tiangong, then autonomously flew a circle around the outpost as the astronauts floated near windows on their spacecraft with cameras “to complete a panoramic image of the space station assembly with the Earth as the background,” the China Manned Space Agency said.

Tiangong’s power-generating solar arrays dominate the views captured by the Shenzhou 16 astronauts. These solar panels span more than half the length of a football field, end to end.

It turns out China may not be finished constructing the Tiangong station. In remarks last month, officials outlined plans to add three more pressurized compartments to expand China’s space station in the coming years.

Tiangong, which means “heavenly palace,” will become a hub for experiments, technology demonstrations, spacecraft assembly, and satellite servicing, said Zhang Qiao, a researcher at the China Academy of Space Technology (CAST). CAST is part of the web of state-owned contractors that build rockets and spacecraft for China’s space program.

“We will build a 180 (metric) tons, six-module assembly in the future,” Zhang said at the International Astronautical Congress last month.

Tiangong times two

In its current configuration, Tiangong has a mass of about 69 metric tons, not including visiting crew and cargo vehicles. That’s about one-sixth the mass of the larger International Space Station, created under a partnership between the United States, Russia, Europe, Japan, and Canada. Chinese officials claim their space station, though significantly smaller than the ISS, has nearly as much capacity for scientific experiments.

“This indicates that the Tiangong space station has high application support efficiency,” Chinese space engineers wrote in a paper published earlier this year in Space: Science & Technology, an open access journal and sister publication of the journal Science.

Now, China is making a longer-term commitment to the Tiangong program, with a blueprint for doubling the size of the space station. Chinese space officials originally said the space station would operate for 10 years. Last month, officials said the lifetime would now extend to 15 years or longer.

This means the Tiangong space station will continue operating at least until the mid-2030s, several years after the planned decommissioning of the International Space Station in 2030, more than 30 years after the launch of the oldest ISS module. NASA’s strategy is to partner with commercial industry to develop a smaller space station to replace the ISS in low-Earth orbit. The idea is that a commercial space station would be cheaper to operate than the ISS, and NASA and other government space agencies could buy access to the privately owned outpost for astronauts and scientific experiments.

NASA isn’t sure commercial space stations will be ready by the time the International Space Station is due for retirement. A senior NASA official recently said it’s possible there will be a gap between the end of the ISS and the arrival of a commercial outpost in low-Earth orbit. “Personally, I don’t think that would be the end of the world,” said Phil McAlister, director of the Commercial Spaceflight Division at NASA Headquarters.

Like the United States, China is moving forward with plans to land astronauts on the Moon by 2030. The US space agency wants to free itself from the cost—more than $3 billion per year—of operating the International Space Station in low-Earth orbit to free up money for missions to the Moon, and eventually to Mars.

China appears to want to keep its government-owned space station in low-Earth orbit at the same time as it mounts an ambitious program of lunar exploration. At a time when the US and China are racing to the Moon, it’s possible China could be the only nation with a continuous human presence in orbit closer to Earth.

Tiangong is already equipped with an airlock to allow astronauts to head outside the station on spacewalks, robotic arms to move equipment around the exterior structure, and experiment racks to support research in human physiology, microgravity physical science, astronomy, Earth science, and technology demonstrations. It also has electric thrusters to maintain its altitude in a more fuel-efficient way than if it used conventional rocket engines.

China’s plans for the station and a new telescope

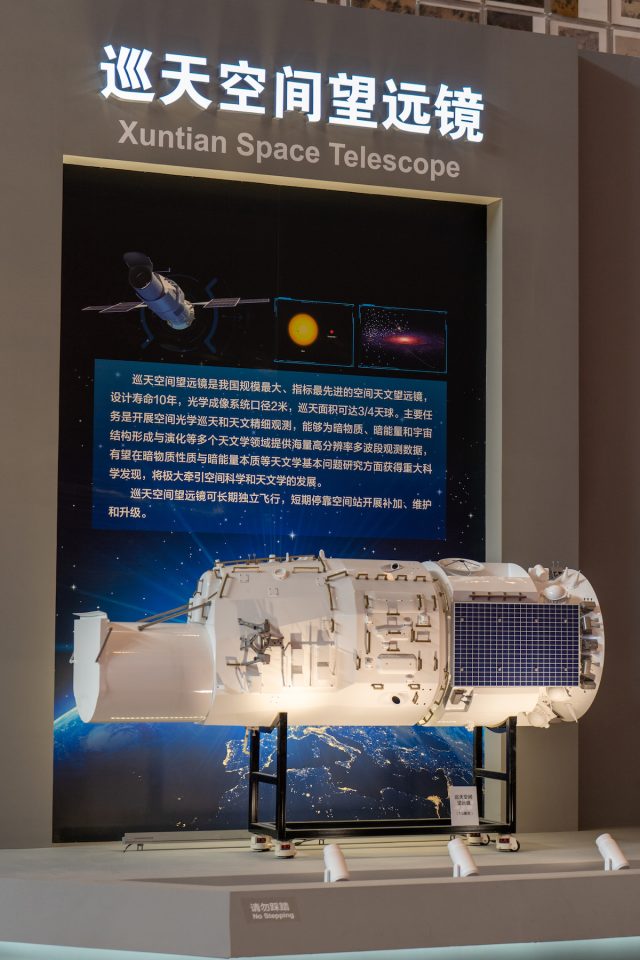

China is building a large astronomy observatory similar in size to the Hubble Space Telescope for launch in 2025. This new telescope, named Xuntian, will fly in an orbit close to the Tiangong station, allowing it to periodically dock with the complex for servicing and refueling. Zhang said more spacecraft will “probably fly co-orbitally” with the Chinese space station in the future.

VCG via Getty Images

Then, perhaps around 2027, China plans to launch an “expansion module” to be installed on the forward end of the space station’s core module. This expansion module will bring more docking ports to the station, opening it up for further expansion to reach about one-third the mass of the ISS. The eventual six-module station could include an inflatable habitat for more volume, and to serve as a testbed for a future inflatable habitat on the surface of the Moon, according to Zhang.

“China’s space station will operate in orbit for a long time, more than 15 years,” he said.

Lyu Congming, who helps oversee scientific research on Tiangong, said more than 100 research projects have been initiated on the space station. Of those, 65 have been implemented, and 48 are ongoing, he said at the International Astronautical Congress in early October.

Chinese officials have put out a call for international cooperation on the Tiangong space station. China has 10 cooperative research projects with the European Space Agency, according to Lyu, and there are opportunities for other countries to supply individual experiments, new technologies such as robotic arms or life support, and even entire international modules to join the Tiangong complex.

Long March

The launch of the Xuntian telescope and the possible addition of three new modules to the Tiangong station will require more flights of China’s Long March 5B rocket, a heavy-lifter that is unique among launch vehicles because it does not require an upper stage to put its payload into orbit. That means the Long March 5B’s huge core stage enters orbit itself. On previous launches carrying up large sections of the Tiangong station, the Long March 5B core stage remained in orbit for several days to several weeks until atmospheric drag naturally pulled the rocket back to Earth.

Most of the rocket burned up during reentry, but this booster stage is so massive that large fragments fell to the ground, or into the sea, intact. This triggered protests from US officials, including NASA Administrator Bill Nelson, who cited the risk of injury, death, or property damage from falling metal from the Long March 5B.

Unless China has redesigned parts of the Long March 5B core stage, we may be watching the skies again as expansion modules go up to the Tiangong station.

Dr. Thomas Hughes is a UK-based scientist and science communicator who makes complex topics accessible to readers. His articles explore breakthroughs in various scientific disciplines, from space exploration to cutting-edge research.