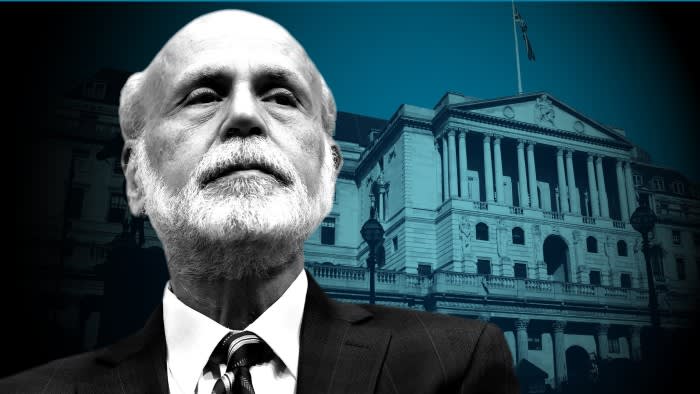

Ben Bernanke was brutally honest about the failings of the Bank of England’s economic modelling when he published a long-awaited review of its forecasting processes on Friday.

But the man who led the US Federal Reserve in its response to the 2008-09 global financial crisis ducked the big question for economists: whether the UK’s central bank should start publishing its own views on how interest rates are likely to evolve beyond the immediate policy decision.

Bernanke’s review, commissioned after the BoE was fiercely criticised for failing to predict the post-pandemic surge in inflation, was billed as a “once-in-a-generation opportunity” to improve the UK’s framework for monetary policy.

This has been largely unchanged since the inflation-targeting regime was put in place by Tony Blair’s Labour government in 1997.

Yet his verdict, in a strongly worded 75-page document that ranges over flaws in the BoE’s software to the way it deploys staff with doctoral degrees, was “strikingly technocratic”, according to James Smith, a former staffer at the central bank who is now research director at the Resolution Foundation think- tank.

Bernanke gave a detailed prescription for the BoE to fix “significant shortcomings” in the main model it uses to produce forecasts — paying more attention, for example, to problems with labour markets and productivity, and the interaction between prices and wages.

He slammed the central bank for “material under-investment” in its forecasting tools, with “makeshift fixes” resulting in “a complicated and unwieldy system” that sucked up staff time.

The BoE had been slow to spot structural changes in the economy because it had been forced to use human judgment to “paper over problems with the models”, he noted.

Bernanke also urged the Monetary Policy Committee, which sets interest rates, to end a heavy reliance on its central economic forecast as a communication tool.

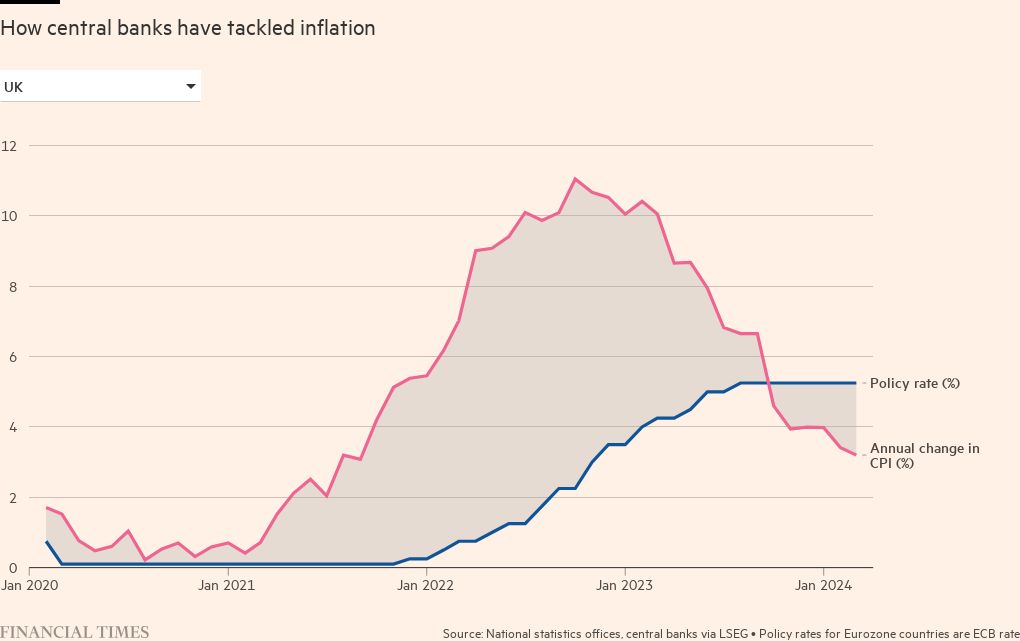

Instead, the nine-member panel, which has lifted rates to a 16-year high of 5.25 per cent, should regularly publish a range of alternative scenarios — a move that would help rate-setters compare possible policy choices and learn from previous mistakes, as well as explain their decisions.

Bernanke said putting more weight on alternative scenarios would help the BoE address one of the biggest communication challenges it faces: the fact that its central forecast is based on market expectations of how interest rates will evolve in future.

This convention means the MPC can find itself forecasting a recession against its own best judgment, Bernanke said, noting: “There can be instances where the committee is basically thinking market rates are too high . . . if they give a forecast based on those higher rates, they will get a different forecast from what they actually think is going to happen.”

Yet Bernanke said recent forecasting errors had been no worse than those of other central banks and independent analysts. He also refrained from passing judgment on the BoE’s policy decisions, although UK politicians have castigated the central bank for allowing inflation to peak, at 11.1 per cent, higher than in either the US or eurozone.

Crucially, however, Bernanke held back from recommending the one big change many economists would like to see — a move to forecasts based on MPC members’ own collective or individual view of where official interest rates are headed, rather than on market expectations.

He described this as an “aggressive approach” that would be “highly consequential” and should therefore be left to future deliberations.

“It’s a real miss,” said Paul Dales, chief UK economist at consultancy Capital Economics, adding that it would be “a huge improvement” if the MPC published its own projections for rates and showed what action it thought was needed to hit the 2 per cent inflation target.

“It would have been clear, transparent and similar to the procedures of the central banks in the US, Norway, Sweden, New Zealand and South Africa,” Dales said.

Michael Saunders, a former rate-setter and now senior adviser at consultancy Oxford Economics, said that while Bernanke’s proposals were “sensible”, he also thought the MPC should publish its preferred path for interest rates, and would have liked the review to address the subject.

However, some economists said that although Bernanke might be reluctant to put pressure on the BoE, he had set out a clear course the central bank could choose to take in future, if views among senior officials changed.

At a press conference with Bernanke, Andrew Bailey outlined the reservations of some MPC members about publishing an interest rate forecast. The BoE governor described it as “a very strong form of guidance” that could mean the BoE being forced to justify itself if it later changed its view on how to act.

But Bernanke said this had not proved to be a problem in the US — where at his instigation the Fed adopted the so-called “dot plot” showing officials’ projections of rates — or in countries such as Norway and Sweden, whose central banks publish rate forecasts.

However, he acknowledged that publishing rate projections could be logistically difficult and risked at times forcing rate-setters to “take a stand when you don’t feel it’s appropriate”, when the outlook was uncertain.

This meant the idea “should be on the table” but that “operationally there are many steps to take before the BoE considers it”, Bernanke said.

Some economists suggested opinion among senior officials might swing in favour of the idea over time. Ben Broadbent, a deputy governor who has previously opposed releasing rate projections, is set to stand down later this year.

Smith, at the Resolution Foundation, said Bernanke appeared to be “nudging the Bank to move to the vanguard in transparency and clarity of policymaking,” adding: “He’s given the BoE the option of doing something pretty radical but he hadn’t pushed them to do it.”

Bailey has left all options open for now, saying on Friday that the BoE would give a “clear steer” on how it planned to act on Bernanke’s recommendations by the end of the year.

But Saunders said calling the review a “once-in-a-generation” opportunity could be a mistake, adding: “This shouldn’t be the last word for the next 25 years. This should be something the BoE does on a regular basis.”

Robert Johnson is a UK-based business writer specializing in finance and entrepreneurship. With an eye for market trends and a keen interest in the corporate world, he offers readers valuable insights into business developments.