According to National Geographic, the Great Pacific Garbage Patch is a collection of marine debris in the North Pacific Ocean. It’s also called the Pacific trash vortex, comprised of two distinct collections of debris bounded by the massive North Pacific Subtropical Gyre.

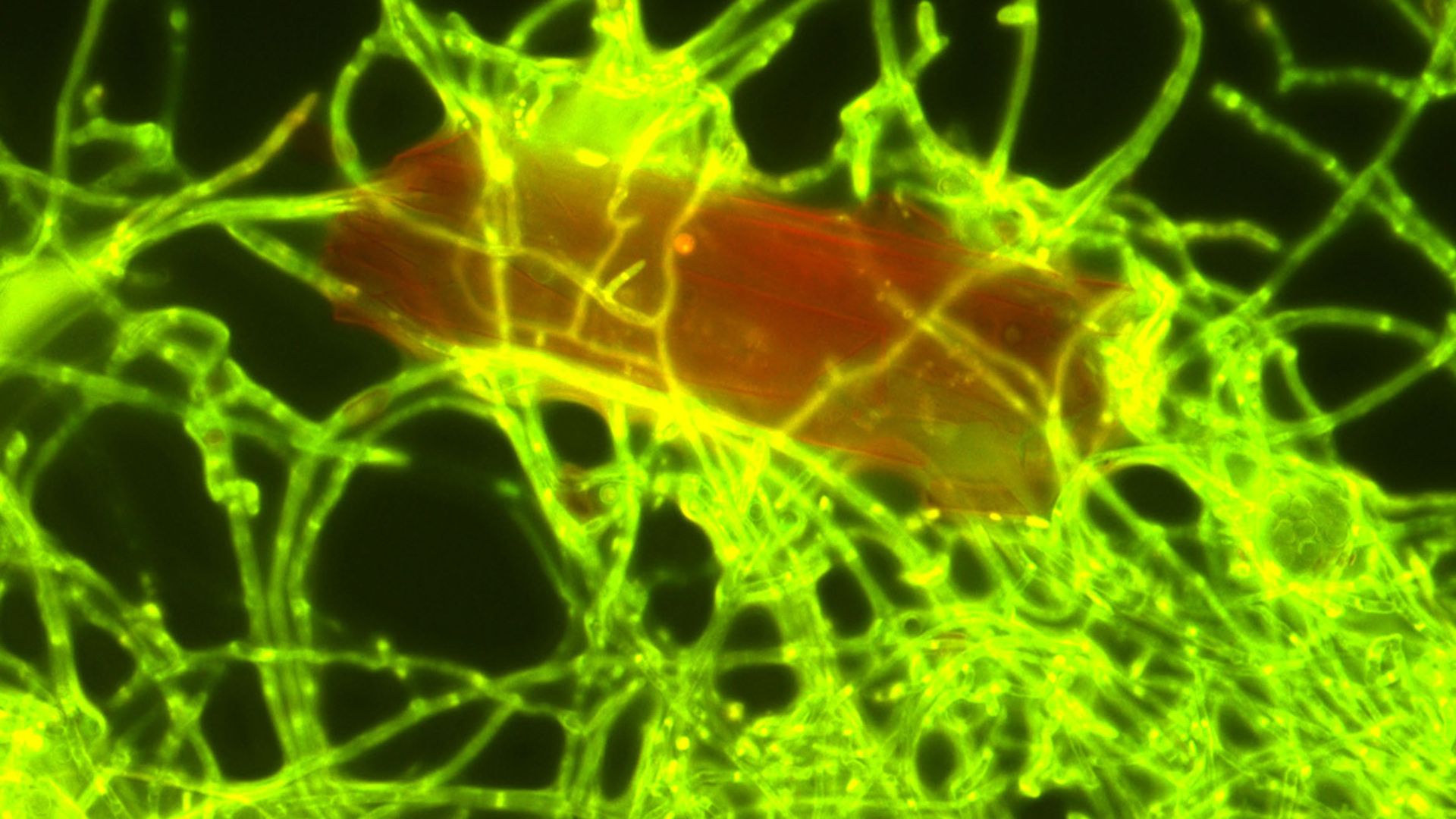

Now scientists have investigated plastic debris found floating in the Great Pacific Garbage Patch and stumbled upon a marine fungus known as Parengyodontium album.

This discovery captivated scientists due to the fungus’s unique ability to break down polyethylene, a common form of marine plastic pollution.

Marine fungus could recede oceanic plastic pollution

This fungus adds to a small list of fungi known to degrade plastic, offering a potential biological solution to combat oceanic plastic pollution.

Scientists separated the fungus from plastic debris collected from the Great Pacific Garbage Patch and examined it in the laboratory. They demonstrated the plastic-degrading capabilities of the fungus by subjecting it to polyethylene (PE), a common type of plastic.

The PE was treated with UV radiation to simulate sunlight exposure, as plastic in the ocean often undergoes photodegradation. After this, the researchers monitored the breakdown of the plastic by P. album over some time.

They quantified the rate of plastic degradation and analyzed the conversion of polyethylene into carbon dioxide.

Additionally, they employed advanced methods such as stable isotope probing assays and nanoSIMS analysis to trace the incorporation of plastic-derived carbon into fungal biomass, further confirming the plastic-degrading capabilities of P. album.

These experiments provided concrete evidence of the fungus’s capacity to degrade polyethylene, marking a significant step in understanding and potentially mitigating oceanic plastic pollution.

Quantifying the degradation process

“What makes this research scientifically outstanding, is that we can quantify the degradation process,” lead author Annika Vaksmaa said in the paper.

The team noticed that the breakdown of PE by P. album appears to be at a rate of roughly 0.05 percent per day.

“Our measurements also showed that the fungus doesn’t use much of the carbon coming from the PE when breaking it down. Most of the PE that P. album uses is converted into carbon dioxide, which the fungus excretes again,” added Vaksmaa.

The discovery of the marine fungus presents a significant step forward in the race to mitigate climate change and reduce plastic pollution accumulating in marine environments.

Alluding to P. album, Vaksmaa explained: “In the lab, P. album only breaks down PE that has been exposed to UV-light at least for a short period of time. That means that in the ocean, the fungus can only degrade plastic that has been floating near the surface initially.”

So far only four other species have been known to possess plastic-degrading fungus, however, a considerable amount of bacteria have been established to degrade plastic.

“Large amounts of plastics end up in subtropical gyres, ring-shaped currents in oceans in which seawater is almost stationary,” stated Vaksmaa.

“That means once the plastic has been carried there, it gets trapped there. Some 80 million kilograms of floating plastic have already accumulated in the North Pacific Subtropical Gyre in the Pacific Ocean alone, which is only one of the six large gyres worldwide.”

The research was conducted by marine microbiologists from the Royal Netherlands Institute for Sea Research (NIOZ), in collaboration with scientists from Utrecht University, the Ocean Cleanup Copenhagen, and St. Gallen, Switzerland.

The study was published in the journal – Science of The Total Environment.

Study abstract:

Plastic pollution in the marine realm is a severe environmental problem. Nevertheless, plastic may also serve as a potential carbon and energy source for microbes, yet the contribution of marine microbes, especially marine fungi to plastic degradation is not well constrained. We isolated the fungus Parengyodontium album from floating plastic debris in the North Pacific Subtropical Gyre and measured fungal-mediated mineralization rates (conversion to CO2) of polyethylene (PE) by applying stable isotope probing assays with 13C-PE over 9 days of incubation. When the PE was pretreated with UV light, the biodegradation rate of the initially added PE was 0.044 %/day. Furthermore, we traced the incorporation of PE-derived 13C carbon into P. album biomass using nanoSIMS and fatty acid analysis. Despite the high mineralization rate of the UV-treated 13C-PE, incorporation of PE-derived 13C into fungal cells was minor, and 13C incorporation was not detectable for the non-treated PE. Together, our results reveal the potential of P. album to degrade PE in the marine environment and to mineralize it to CO2. However, the initial photodegradation of PE is crucial for P. album to metabolize the PE-derived carbon.

ABOUT THE EDITOR

Shubhangi Dua As a quirky and imaginative multi-media journalist with a Masters in Magazine Journalism, I’m always cooking up fresh ideas and finding innovative ways to tell stories. I’ve dabbled in various realms of media, from wielding a pen as a writer to capturing moments as a photographer, and even strategizing on social media. With my creative spirit and eye for detail, I’ve worked across the dynamic landscape of multimedia journalism and written about sports, lifestyle, art, culture, health and wellbeing at Further Magazine, Alt.Cardiff and The Hindu. I’m on a mission to create a media landscape that’s as diverse as a spotify playlist. From India to Wales and now England, my journey has been filled with adventures that inspire my paintings, cooking, and writing.

Dr. Thomas Hughes is a UK-based scientist and science communicator who makes complex topics accessible to readers. His articles explore breakthroughs in various scientific disciplines, from space exploration to cutting-edge research.