It’s already been more than fifty years since a human last stepped foot on another celestial body, and now that NASA has officially pushed back key elements of their Artemis program, we’re going to be waiting a bit longer before it happens again. What’s a few years compared to half a century?

More than just an acknowledgement of the Artemis delays, the press conference did include details on the specific issues that were holding up the program. In addition several team members were able to share information about the systems and components they’re responsible for, including insight into the hardware that’s already complete and what still needs more development time. Finally, the public was given an update on what NASA’s plans look like after landing on the Moon during the Artemis III mission, including their plans for constructing and utilizing the Lunar Gateway station.

With the understanding that even these latest plans are subject to potential changes or delays over the coming years, let’s take a look at the revised Artemis timeline.

2025 – Artemis II

Originally scheduled to happen by the end of 2024, Artemis II now has a No Earlier Than (NET) date of September 2025. Beyond being pushed back a year, the mission itself has not changed, and will still see four astronauts travel from Earth orbit to the Moon and back aboard the Orion capsule. This mission is roughly analogous to Apollo 8 in that the crew will operate their craft within close proximity to the Moon, but won’t attempt to land. Unlike Apollo 8 however, Artemis II will not enter lunar orbit and instead make a single close pass around the far side of the Moon at a distance of approximately 10,000 kilometers (6,200 miles).

NASA says the delay is largely due to three major technical issues with the Orion capsule that need to be addressed before it can carry astronauts:

Heat Shield Performance

While the Artemis I mission in 2022 was a complete success, engineers did notice greater than expected erosion of the AVCOAT heat shield material that protects the Orion capsule during reentry. The shield is designed to be ablative, and NASA says there was still a “significant amount of margin” left on the spacecraft, but the fact that the damage didn’t track with pre-flight simulations has mission planners concerned.

As Artemis II will be flying a very similar mission profile, engineers wanted to take a closer look at this anomaly, looking to not only improve their simulations but to see if there is some way the erosion could be reduced on future flights.

Amit Kshatriya, the Deputy Associate Administrator for the Moon to Mars Program, says that team feels they have a good understanding of the issue, and hope to have their investigation completed by spring.

Life Support Design Flaw

A design flaw found in certain life support components currently being installed in the Orion capsule for Artemis III lead to the decision to go back and replace the hardware that had already been installed in the Artemis II capsule. The components were explained to be responsible for controlling various valves in the system, including those used by the carbon dioxide scrubbers.

Given the fact that the life support system in the Artemis II capsule had already passed its qualification checks before the flaw was identified, some consideration had been given to using the flawed components, perhaps with some procedural changes to avoid triggering a malfunction. But ultimately it was decided that crew safety couldn’t be compromised, and that the hardware needed to be replaced.

Unfortunately, with assembly of the the Artemis II capsule so far along, accessing the components in order to replace them is a considerable undertaking. The capsule will also have to redo various qualification checks once reassembled, further delaying its completion.

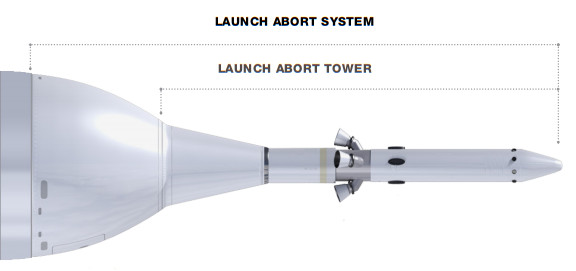

Potential Power Loss During Abort

The final major issue was identified was with the Orion capsule’s batteries, which testing showed could fail when subjected to the vibrations expected during an in-flight abort.

Kshatriya said the investigation into this particular issue is still in the early stages, and a decision has yet to be made on how it will be addressed. But as with the life support electronics, should the decision be made to remove the batteries, it will likely add several additional months to the capsule’s assembly and testing time.

2026 – Artemis III

Artemis III is also being pushed back by roughly one year, in part due to the delay of Artemis II. As a number of major systems are reused from one Orion capsule to the next (such as the avionics), technicians need several months to remove those components and install them in the newer spacecraft.

But even if Artemis II hadn’t been pushed back, NASA says there are two major areas of development that need more time before they can put astronauts back on the Moon:

Human Landing System

The Human Landing System, or HLS, is the official Artemis designation of the customized version of SpaceX’s Starship that will take astronauts down to the lunar surface. NASA says they are satisfied with the pace of development for Starship, which should make its third test flight as soon as next month. But there are concerns about the in-space refueling procedure that will be necessary for HLS to reach the Moon, which has never been attempted in space.

For SpaceX’s part, they believe that many of the key elements of orbital refueling can be tested and perfected at a smaller scale, allowing them to rapidly iterate until the bugs are worked out. Jessica Jensen, VP of Customer Operations and Integration at SpaceX, also said that the lessons the company is currently learning on transporting and loading the vehicle’s cryogenic propellants on the ground will be directly relatable to how they will perform similar operations in orbit.

There’s also the matter of developing a Starship-Orion docking mechanism that will allow the crew to transfer from one vehicle to the other. This is not so much a technical challenge, as SpaceX already has real-world experience in building docking hardware for the Crew Dragon, but will still require time to develop and test.

Finally, Starship still needs to complete an uncrewed demonstration mission that includes all the steps required to complete Artemis III. That means launching into Earth orbit, being refueled, travelling to the Moon, successfully landing, and of course, lifting off the surface and returning to space. This test is currently scheduled for 2025, which will give SpaceX and NASA time to go over the results and make any necessary changes to the final mission.

Next-Generation Spacesuits

After determining that their own version wouldn’t be ready in time, NASA turned to commercial partners to develop a next-generation spacesuit for use on the lunar surface. Axiom Space, who are currently orchestrating private missions to the International Space Station and hope to eventually build their own orbital facility, ended up winning the competition.

NASA gave the public a peek at what the new suits would look like in March of 2023, and then in October, Axiom announced they were partnering with Italian luxury designer Prada to improve the design. Since then there hasn’t been much news about the suits or their development, but given the fact that the suits have been identified as one of the things holding Artemis III back, we can assume things aren’t progressing as quickly as hoped.

2028 – Artemis IV

The date for Artemis IV, the first post-landing mission of NASA’s lunar program, actually hasn’t changed. It was always scheduled for 2028, but details on what the mission would entail were always a little vague.

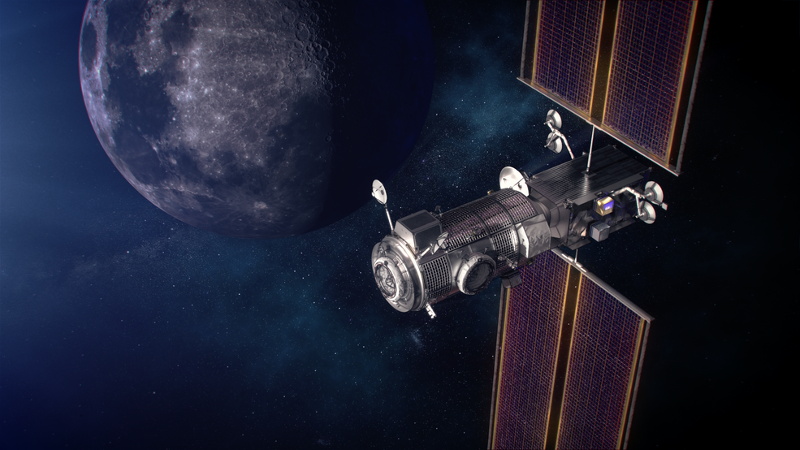

That situation hasn’t improved by much, but we now at least have confirmation that NASA plans to have the first modules of the Lunar Gateway station ready in orbit around the Moon by the time the Artemis IV astronauts arrive. No launch date for these modules, which are slated to fly on a Falcon Heavy, was given — but they’d have to be on their way to the Moon by early 2027 at the latest for the timing to work out.

A Block 1B version of the SLS, with greatly improved payload capacity, will send both an Orion capsule and the International Habitation Module (I-HAB) towards the Gateway, where an upgraded version of the Starship HLS will be waiting. After the astronauts deliver the module to the station, they will descend to the surface to complete further mission objectives.

Given how far out Artemis IV is, there’s little point in speculating what kind of hardware delays it could run into, but clearly there are many moving parts involved. Not only do the two first modules of the Gateway need to be completed and launched to the Moon, but the I-HAB needs to be ready, as does SLS 1B.

To further complicate matters, the mass of the combined SLS 1B and I-HAB is so great that a new launch platform will need to be used, a project that has already been delayed and is significantly over budget. In a June 2022 report from NASA’s Office of Inspector General, it was estimated that the new launch platform wouldn’t be ready until at least the end of 2026.

Terms Subject to Change

It was an open secret that the previous Artemis timeline wasn’t realistic — if astronauts were to be headed to the Moon before the end of 2024, it’s likely we would have already seen the SLS rocket they’ll be riding to orbit in going through its final tests. But until the announcement was officially made, NASA had to keep telling the public that things were on track.

Even this revised timeline is arguably pushing what the agency is capable of, given their divided attention and relatively limited budget. During the press conference, Kshatriya admitted that the 2026 date for Artemis III is “very aggressive”, suggesting that this isn’t the last time NASA is going to have to shuffle their plans around before they can finally put some fresh boot prints on the lunar surface.

Dr. Thomas Hughes is a UK-based scientist and science communicator who makes complex topics accessible to readers. His articles explore breakthroughs in various scientific disciplines, from space exploration to cutting-edge research.