It was a warm Saturday morning in the summer of 1994. I was working at Big Red Software, a video game developer then based in Southam, Warwickshire, just up the road from Codemasters. Naturally, we’d already played Doom, which had been released a few months before and was still the hottest game in the world. Our programmer Fred Williams bought a copy of the shareware version in the Game store on Leamington high street – you could download it for free, but back then the internet was super slow and super expensive, unlike Game, which was convenient and super expensive. Indeed one of the cleverest business decisions John Romero made was allowing software companies with already established retail channels to box up and sell Shareware Doom at no charge from Id Software. It allowed the game to go viral at a time when “going viral” still meant catching chicken pox at your mate’s birthday party. As there was no copy protection on the disc, almost as soon as Fred brought it to the office, it was on everyone’s computers. We were hooked.

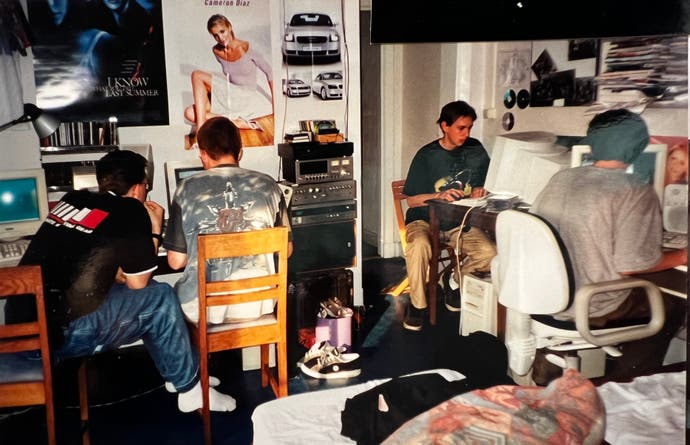

But after a few weeks of play there was still one thing we hadn’t tried – multiplayer. Doom launched with what would now be considered a very basic online mode. It supported peer-to-peer play via dial-up modems or you could link up to four players via a local area network. Being a game developer we had one of those. So that’s what we did that Saturday morning. We went into work to connect our PCs across the office LAN and play against each other for the first time.

We got there at ten in the morning planning a couple of hours play. Although there was no matchmaking or lobby system back then, it wasn’t that hard to set up. “We connected via IPX LAN,” recalls Williams. “You just had to run its setup program, say you’re doing an X player LAN game in its little DOS text-mode setup program, wait for everyone to do the same, and it auto-launched when there were that many players.”

We knew about the brilliantly paced design of Doom. But what we didn’t realise, until we hit start on a four-player co-op game, was how it would feel to share this bizarre world with friends – to see their avatars on screen fighting imps, getting blown to pieces by exploding oil drums. You’ve got to try to remember that shared virtual worlds were the stuff of science fiction at the time. There were a few two-player peer-to-peer games around, but this was a visceral shooter set on a ruined space base. This was the preserve of William Gibson and Neal Stephenson, the Star Trek Holodeck and Tron. We weren’t actually supposed to go there ourselves.

Fred was the most experienced and skilled player, he was speeding ahead, clearing rooms. I was just wandering about in awe, like a flaneur exploring 19th century Paris, but with a chaingun. I’d get these moments of coming to a ledge, looking out and seeing Fred and Jon in the distance unloading shotguns into a hulking Cyber Demon, hearing them both yell from the room down the hall. It was utterly enthralling, utterly new. According to Id programmer Dave Taylor, this sheer noisy joy was happening at Id Software too. “It was all about Deathmatch,” he says. “Especially with Romero in the room. He was so fucking funny. He had such beautiful insults, and when you killed him, he had such satisfying cries of agony. And it made me wonder, how many other people are going to dig that kind of insult/agony deathmatch chatter?”

It turned out, a lot. Even before release it was being replicated throughout the world of games. “The point I realised Doom was going to be massive was when I got to take a trip back to [my old workplace] Microprose in the November before it was released,” recalls co-level designer, Sandy Petersen. “I showed it to my former coworkers, and they just went nuts over it. They just couldn’t believe it. I left a preview copy with them and later on, I heard that it delayed several games by up to six months.

“And the thing I heard most from other developers was, ‘Oh, they would never let us do a game like this, it’s too violent’. And then of course, a couple years later, everyone’s doing it.”

I’ve no doubt that the explosion of the FPS genre in the wake of Doom was the result of commercial decisions – it made millions of dollars after all. But I think the technical desire, the ability to build networked games in the pre-broadband era, came from studios like ours playing LAN Doom in our free time (or on work time) and wanting, no needing, to figure out how it worked and how it could be replicated. A year later, we had Modem play in our own game, Tank Commander and I’m sure our Doom sessions paved the way for that.

“We were all struck by how advanced the game was for the time,” says Jon Cartwright, then a coder at Big Red, now a video game design consultant in Australia “Of course, the tech had its limitations, but like any good game it just lent into the limitations and pushed as far as it could go. I do remember Paul [Ransom, Big Red’s MD) saying that this kind of engine was the future and we needed to build one. It was not too long after that we ended up getting dddWare and went on to build Tank Commander and Big Red Racing. Doom was incredibly specialised and really only rendered vertical rectangles as well as flat floor polygons. And of course, like Wolfenstein all the enemies were 2D sprites with a bunch of frames. But they looked fantastic, and as horrific as they needed to, and critically everything that Doom did was very, very efficient in a time when 3D accelerator cards weren’t around.”

Id Software also made another seemingly eccentric decision which turned out to be genius – they ported Doom to Unix and a range of Unix-like operating systems. This was the shared computing platform used in serious workplaces throughout the world – now it ran Doom multiplayer. “That was responsible for getting it into the visual effects and scientific communities, which was kind of an interesting side effect,” says Taylor, who handled a lot of the Doom conversions. “At the time, Unix workstations were like today’s modern operating systems. It was the barely tolerable solution for computing for scientists, and they just would never look down their nose at Dos. It would just be like, I’m not going to subject myself to that. I have a PhD.” But getting these geeky communities onboard via the LAN mode was instrumental in growing the audience for the game and ensuring its dispersal. When I ask Taylor what the scientists were doing with Doom, he shrugs his shoulders. “I don’t know, science shit? They just happened to be on Unix workstations because they had to do these fancy simulations of things. I think they were just avoiding work with Doom just like everybody else.”

Hours flew by at Big Red. Outside the closed blinds, night was drawing in, but we didn’t notice. We started on Deathmatch and the vibe changed – it was more tense and emotional. That sense of real human competition. After a few hours, we were all developing different styles of play revolving around different weapons. We’d all played two- and even four-player local multiplayer games on home computers and consoles before, but this was something new – competing in first-person in a 3D space, with a range of weapons and an architecturally complex environment – it required new skills, new conventions – a new language almost. It felt like a whole new universe opening up. And the fact that a LAN was the easiest way to play Doom as a multiplayer game, meant that gamers had to get out and meet.

Doom didn’t invent the LAN party concept, but it gave it a big kick up the router ensuring that it ruled the competitive gaming scene in the late-90s and early 2000s, As Taylor recalls, “We had this really compelling multiplayer format that forced you to come together in a LAN party. Well, there’s your social network! You’re coming together, forming the party, now you’re socialising. and that concretes the bond. tIt wasn’t everybody that was doing this multiplayer stuff, but God damn, it was a stunning amount of people. And so we were really knitting together these communities.”

That was it, I think. That was what it felt like – that we were at the very start of this new global community of game players. Playing Doom over a LAN was happening to me at the same time as I was discovering Usenet and online forums. Later, the Dwango service made it possible to play Doom over the internet (well, kind of, it was a long distance dial-up service.), and this expanded the experience even further.

A year later, our own 3D war game, Tank Commander was deep into development when Paul Ransom signed a deal to support the new CyberMaxx VR headset. They sent us a sample and it was decided that some idiot in the office had to test it out – that idiot was me. Tank Commander wasn’t quite ready, but Doom was one of the headset’s launch titles so I tried that. The Cybermaxx was an enormous and uncomfortable headset and its two eyepieces seemed to poke right into your skull. Also, it was doing VR in 505×230 resolution with significant lag. But still, there was Doom once again, showing everyone the future – at least that’s what I was thinking 20 minutes later while vomiting profusely into the office toilet.

I feel kind of sorry for the generations of gamers beneath me, who have had broadband all their lives. They will never know the wonder of stepping into a hellish space station and seeing their friends in there too, and this being something totally new and arcane and wondrous. When I finally left the office very late that night, I felt differently about games and what they could do. I felt that, in some small way, I had to be a part of it. Thirty years later, I still am, and so is Doom.

Laura Adams is a tech enthusiast residing in the UK. Her articles cover the latest technological innovations, from AI to consumer gadgets, providing readers with a glimpse into the future of technology.