All Nando Parrado remembers is a deep black hole and one recurring thought: “I’m dead. I’m dead. This is death. It’s so black that this is death.” Hours passed, maybe days. Then, a new thought: “I’m thirsty. I’m craving water. If I’m dead, I cannot crave water.”

His awareness increased. Why was it cold? Why did his head throb? Then, voices. Parrado opened his eyes.

“I remember the clear, beautiful faces of my friends,” he recalls. “And they were saying: ‘Nando, are you OK? Nando, are you OK?’ I was not OK. ‘The plane crashed.’” He looked around. He was inside a mangled fuselage that had rolled on to its side. The damage was catastrophic: exposed pipes and cables, crumpled metal, shattered plastic, detritus everywhere.

He pressed the side of his head, his hair clumped with clotted blood, the edges of splintered bone. His friend Roberto Canessa explained the plane they were travelling on had hit a mountain three days before and Parrado had been unconscious since. Parrado’s thoughts turned to his mother, Eugenia, and sister Susy.

“They told me: ‘Nando, your mother is dead. Panchito is dead.’” Francisco “Panchito” Abal was his best friend. He’d made Parrado give up the window seat for him during the flight. “Panchito was my brother. He lived two or three days a week in my home, he used my clothes.” Susy was gravely injured, lying on the floor by the cockpit.

“I crawled to where my sister was and I embraced her on the floor. She couldn’t move. She couldn’t talk. She could only move her eyes. She lost her shoes in the crash and her feet were purple. Those are the images that I have. I stayed with her. I melted snow with my mouth and gave her water because we didn’t have anything. We didn’t have cups.”

Parrado didn’t leave her side until the next morning, when he staggered outside. What was left of the plane had stopped on the slope of a glacier. The eastern horizon offered only snow-capped peaks and plunging valleys. In every other direction they were ensnared by mountains. “I saw the magnitude of the place we were in. It’s immense. It’s huge,” he says. “And I said: ‘Fuck. This is going to be horrible. How are we going to get out of here? They won’t find us here.’”

Parrado was right – no rescue team found them. But, in December 1972, 72 days after Uruguayan air force flight 571 struck a ridge and crashed deep in the Andes, he and 15 other passengers did make it off the mountain alive. It is an astonishing tale of survival. At the time, newspapers christened the story The Miracle of the Andes. Parrado, now 73 and speaking over videocall from his home in Montevideo, Uruguay, didn’t see it that way. “I think it was the effort of a group of young people who trusted each other beyond anything that you can imagine. And the result is that we are alive.”

Parrado is a pragmatist. More than 50 years on, he recounts the events with a careful matter-of-factness. There was a 26-year period where he didn’t speak about his experiences at all, but he was eventually convinced to do so and has since flown all over the world telling his story. He insists he’s not a motivational speaker, but I’m not so sure. His immediate warmth, with his rousing, booming voice and lyrical intonation leaves you invigorated as he speaks about his time in the Andes, his love for his father, Seler, and his zest for life.

Parrado doesn’t often give interviews, but he wanted to speak in the run-up to the release of Netflix’s thriller Society of the Snow, the second major film to tell the survivors’ story, after 1993’s Alive. Parrado has seen the new film twice and hails it as a “magnificent piece of film-making”. (It’s a likely nominee for best international feature film at the Academy Awards.) “I told the director: ‘After people see this film, they will really understand what we went through,” he says. “He has captured the essence of what we went through very, very well. Even my wife, when the movie finished, she grabbed my arm, she said: ‘Fuck, man. I didn’t know it was so hard. Now I understand.’”

In October 1972, Parrado was 22, just a regular middle-class Uruguayan man waiting to start university. He helped in his father’s hardware shop, tore around on his motorcycle, chased girls and played for his school alumni rugby team, Old Christians. “It was an exciting time.” He’d known most of the team for more than a decade and had already travelled to Chile with them for a match. When a second trip was announced, he wasn’t going to miss it.

Their team captain, Marcelo Perez, had chartered a plane to take them to Santiago, Chile. Parrado’s father dropped him off at Montevideo airport, along with his mother and younger sister (his older sister, Graciela, stayed home). Due to bad weather, the flight touched down early in Mendoza in Argentina, where the team stayed overnight. The pilots delayed for much of the next day (and were jeered by some of the rugby team for doing so), but the plane had been leased from the Uruguayan air force and the law forbade it from being on Argentinian soil for more than 24 hours. They boarded at 2pm and took off shortly afterwards. It was the worst time of day to fly over the Andes, with the afternoon’s warm air rising to create atmospheric instability.

When Parrado thinks about the flight now, he is struck by his naivety. “Today, I would never go near that aeroplane,” he says. “A Fairchild FH-227D, very underpowered engines, full of people, completely loaded, flying over the highest mountains in South America, in bad weather. I mean, no way.”

The plane took off from Mendoza on Friday 13 October, a fact that wasn’t lost on the rugby team, who joked about the date’s unlucky symbolism. On board were 45 people – the team, friends, family and crew, as well as a stranger who had paid for a seat so she could get to a wedding. Flying direct over the Andes wasn’t possible. The plane’s maximum cruising altitude was 6,858 metres (22,500 feet); Aconcagua, the highest mountain in the range, is 6,960 metres. Instread, they would follow a U-shaped route: 100 miles south, then into the Andes and over Planchon Pass, where the ridges are lower, before heading north to Santiago. The flight should have taken 90 minutes.

An hour or so into the flight, the inexperienced co-pilot misjudged his position – most likely due to cloud cover or miscalculating headwinds. He turned the aircraft north too early and headed deeper into the Andes. Unaware of his error, he began the descent to land.

The Fairchild entered thick fog. The steward told the passengers to fasten their seatbelts. Severe turbulence shook the plane. It hit an air pocket and dropped what felt like hundreds of feet. Panchito elbowed Parrado next to him and pointed outside to the mountain, perilously close to the wing tip. Parrado remembers only flashes: the realisation they shouldn’t be that close, some shouts, the worried faces of his mother and sister. Then the plane began climbing, climbing, climbing, its engine screaming, its fuselage vibrating violently. “I heard this sound, like an implosion,” Parrado says, “like a Formula One car hitting a wall head-on.” The sky opened above him. He was thrown forward in his seat. Then: “I died without realising I was dying. I went into a very black piece of, I don’t know what … of the universe?”

Parrado’s peers would later fill him in. The pilots had tried to lift the plane over an oncoming mountain, but the belly smashed into the ridge. The wings broke away. The plane’s left propeller cut through the fuselage. The tail snapped off at roughly the point where Parrado was sitting. The fuselage tobogganed down the mountain at terrifying speed. When it stopped, the cabin seats were flung forward, ripping through their anchors and folding into one another, crushing several passengers.

Those who could immediately worked through the wreckage to help the injured and the trapped. Perez, the team captain, took charge. Gustavo Zerbino and Canessa, both medical students, did what they could; bandaging fractured bones with strips of clothing and cooling them in the snow. They found the pilot, trapped in the crumpled cockpit. Before he died, he told them they had passed Curicó; they were at the western limits of the Andes. Back in the fuselage, a makeshift wall was constructed from suitcases, seats and plane fragments to shelter from the blistering winds. They covered any holes with snow. Of the 45 on board the flight, 33 survived, and 32 huddled together on the first night.

Parrado was originally presumed dead, which turned out to be a blessing. “They left me in the snow. They didn’t give me any water. They didn’t hydrate me.” Neuroscientists would later tell him that the cold and dehydration stopped his head injury swelling and killing him. Eventually, one of his friends saw enough life in Parrado to warrant pulling him closer into the fuselage and the rest of the group.

From the moment he woke up, there wasn’t a single moment Parrado didn’t feel close to death. The group were more than 3,350 metres up in the Andes, where temperatures can hit -35C. Blizzards raged constantly and the air was so thin it was possible to be out of breath just standing still. The sun blinded and blistered, reflecting off an endless white. One wrong step could lead to being hip-deep in snow. They had no coats, no blankets, no specialist mountaineering equipment of any kind.

What surprised Parrado most was the unbearable thirst. “You need water permanently. You dehydrate five times faster at that altitude than at sea level. And there’s no water, so you have to eat snow.” It was so cold it burned their throats and cracked their lips.

The nights were brutal. The makeshift wall never fully protected them from the wind; the cloth coverings they had ripped from the seats offered little comfort from the cold. Their clothes froze. They punched each other’s arms to improve circulation. They shivered and their teeth chattered so much it was impossible to talk. They huddled together and sought warmth in one another’s breath. “Imagine how small you become that you look for that heat,” says Parrado. Sometimes, all he could do was count the seconds until morning. They would wake up with frost in their hair.

Hope dwindled. On the fourth day they saw a plane overhead, but from that height the white fuselage of the wreckage was invisible to the pilot. On the fifth morning, three boys tried to climb the mountain, crafting snowshoes from cushions tied to their feet with seatbelts. The challenge was too great and they returned by the afternoon. Susy died in Parrado’s arms on the eighth day. At the time, he felt very little. “I learned that at those moments my brain didn’t react to anything that was outside survival. I couldn’t cry. I didn’t feel sorrow.” He buried her the following morning.

Starvation became a real possibility. Some had tried eating leather from torn bits of luggage. They had crashed with the bare minimum: some chocolate, nuts, sweets, crackers, fruit, jars of jam, three bottles of wine and some liquor. Meals would consist of one square of chocolate, or the equivalent. Parrado took three days to eat one chocolate covered peanut. After a week, he knew what had to be done. One night, he turned to his friend Carlitos and told him he was prepared to eat meat from the bodies outside.

“I didn’t have any doubts. I had arrived at the conclusion of my thoughts very clearly. No doubt. This is the only way out,” he says. “Not knowing when you’re going to eat again is the worst fear of a human being. The most primal fear.”

When the conversation was opened up to the group, the debate lasted all afternoon. There were a few holdouts, but most agreed with Parrado. A small group left the fuselage with some glass to cut the meat off. Some pledged their bodies to the others if they died. One of the boys, Roy Harley, had managed to get a transistor radio working, and on day 11 they heard a broadcast saying the rescue attempt would be called off. Everyone started eating after that. “Everybody in that situation … you would have arrived at the same thought. And it’s easier than you think.”

Parrado wanted to leave as soon as he knew the rescue team wasn’t coming, but his injuries were too severe, the weather too savage. Over time they learned the rules of survival: how to look for dangerous crevices, how to melt snow in bottles so that it was warm enough to drink. “We started to acclimatise. You start to learn. I started to learn how to walk in the snow. One month into the ordeal we were mountain men and we knew what to do.”

What they didn’t know was that the plane sat near the base of a couloir – a steep gorge in the mountain where snow builds up. Just over two weeks after the crash, an avalanche struck. Everyone asleep on the floor of the fuselage was buried. Roy Harley had stood up after hearing the avalanche thundering down the mountain; had he not, they would probably have all died. He uncovered three others as quickly as possible, then they began searching for more, wiping snow away from faces so they could breathe, before moving on to dig for the next body.

“I couldn’t move. I was under rubble but I could breathe.” Parrado remained like that for 30 minutes. Of the 27 people left in the fuselage that night, eight died. The survivors were now trapped in a fuselage half-filled with snow. It was dark. They couldn’t stand. Outside, a blizzard roared. After a few hours, Parrado punched a hole in the aircraft’s roof with a cargo pole, drawing in fresh air. They stayed like that for four days, next to the bodies of the dead.

“We didn’t know if we had enough air. We didn’t know if we had two metres, four metres or 50 metres of snow on top,” says Parrado. They heard a second avalanche that night, but it rolled over the already buried plane. “Hell could have been a very comfortable place, I can tell you, if you compare it with those four days under the avalanche.” When the blizzard stopped and it was safe to leave, they dug their way out through the cockpit, working in 15-minute shifts. It took hours.

After the avalanche, Parrado knew the only way off the mountain was to walk. The following weeks were spent training, waiting for the weather to improve and making the necessary equipment: a sleeping bag from sewn-together cushions, a sled crafted from a suitcase. When Parrado ran out of holes on his belt, he knew time was up. He says the decision to leave was the most important he has ever made. “I knew that when I gave the first step to leave the fuselage I was not coming back. This is a kamikaze expedition.”

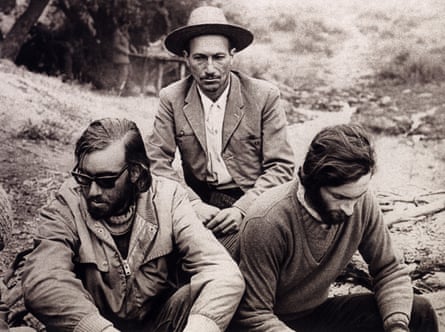

On the 61st day, Parrado, Roberto Canessa and their friend Antonio “Tintin” Vizintín left the fuselage. Based on the pilot’s dying message to them, they believed they just needed to scale the mountain to the west and then head down to Chile. Parrado had layers (three pairs of jeans, three sweaters, four pairs of socks covered in a shopping bag, rugby boots), an aluminium pole for a walking stick, a backpack with three days of meat rations. Before he left, he told those staying behind they could use his family if they ran out of food.

Experts say you shouldn’t climb more than 300 metres a day in such high mountains; the trio cleared twice that in one morning. Altitude sickness kicked in – Parrado’s heart rate soared, he came close to hyperventilation and dehydration. They thought the climb would take them 14 hours; it took three days. On the first night, the temperature dropped so low that their water bottle shattered.

Parrado was the first to reach the summit. They had started the climb at 3,570 metres; the peak sits at 4,600 metres. Any joy he felt reaching the summit evaporated as he looked around. Parrado realised the pilot’s mistake. No green valleys of Chile, just ridges and peaks far off into the horizon.

“We thought we were five kilometres away; we were 80.” He made his life’s next biggest decision: continue west. “I said: ‘Come on, Roberto, I cannot do it alone. Let’s go. If we go back, what for? I’m going to die looking into your eyes and who dies first?’”

Did he expect to die on the trek? “I mean, if I die, if I crash, if it hurts, if I suffer, nothing matters. You are already dead. So if you are still breathing, that’s a bonus. But you cross the invisible gates of death and nothing matters.” Before heading down, Parrado christened the mountain after his father, writing “Mt Seler” in lipstick on a bag that he tucked under a rock. They took Tintin’s rations for the journey and sent him back to the fuselage (he made it back in one hour, using the sled). Parrado and Roberto began their descent.

Day after day, they struggled downwards. The harsh landscape began to soften. They found a river, which they followed. Signs of human life kept them going: signs of camping, manure, cows. Eventually they found three men on the far side of the river. Against its crashing flow, they communicated with notes tied to a rock. The men threw some bread to them, then rode off to get help from the nearest police station, 10 hours away by mule.

Parrado and Canessa had hiked more than 37 miles in 10 days. Parrado believes they could have lasted one more day. “Roberto was very weak. He gave everything that he had. Everybody gave everything that they had. He was the best associate, the best companion, the best friend I could have had in this expedition,” he says.

Many years later, talking to mountaineering experts, he was told that he achieved what they did because of their ignorance: “They told me: ‘Had you known what you were going to face, you would never have left the aeroplane. You never knew what you were going to face and that’s why you made it.’”

When the helicopters arrived with a rescue squad, Parrado was presented with maps. He traced their path. “They said: ‘No, no, no, no, that’s Argentina. That’s 60 or 80km away from here.’” He insisted his friends were there; the rescuers needed a guide. Parrado looked at Canessa, lying on the floor being tended to by a nurse. He looked at the helicopter being stripped for weight. The adrenaline kicked in. “They put me behind the pilot, headphones on and seatbelt and I said: ‘What am I doing?!’”

Eventually, Parrado recognised the valley and the mountains, then the fuselage. As the helicopter circled, the boys emerged.

The helicopter landed. Parrado opened the door and “three of my friends jumped over me like dogs, kissing me and shouting. It was a very surreal and emotional scene. It was their first spark of being alive again.” They couldn’t all fit in the helicopter, so some stayed one more night accompanied by members of the rescue team.

About half an hour later, the helicopter landed at a hospital in San Fernando, Chile. Medical staff rushed toward Parrado with a gurney. “The distance from the helicopter to the entrance of the hospital was about 50 metres. And I said: ‘No. Stop. I crossed the whole Andes on foot. I’m not going on a gurney into this hospital.” He finished his journey on foot.

Parrado never came close to giving up. He accepted death. At points he was almost certain of it. But he never stopped going. “The lighthouse was my father,” he says in a rare moment of sentimentality. “I knew that he thought we were all dead. Only somebody that can lose their family in one second can understand what he was going through.” When Parrado eventually wrote about his experiences in Miracle in the Andes, published in 2006, he did so as a 90th birthday present for his father. “Everything that he taught me at the beginning of my life saved my life,” he says.

After the rescue, Parrado was reunited with his father and older sister, Graciela, at the hospital. Parrado still had enough strength to lift his father up, but he had lost 45kg of his original 100kg. The nurses removed his clothes – the first time he’d taken some of them off in 72 days – and he looked himself in the mirror. “I didn’t recognise myself.” There wasn’t a trace of muscle. “I looked at my legs and there were bones – knees and bones.”

After his discharge, he moved to a hotel in Santiago, along with most of his surviving teammates. For them, it was a carnival atmosphere. “For me, it was different,” says Parrado. “Maybe my ordeal really started when I came back home. My father was sleeping in my bedroom, sometimes on the floor embracing my dog.” On the mantelpiece was a photograph of Parrado with his mother and sister Susy. “All my old friends, they returned to their homes, they were embraced by their family, girlfriends, and the ordeal was finished …”

Their experiences made them celebrities overnight. “For six months afterwards, we were surrounded by journalists everywhere we went.” His gauntness made him instantly recognisable. Paparazzi photographed him; strangers would approach him in the street and shake his hand. Some even said they were envious of his experience.

Officials from the Catholic church said the survivors had committed no sin by eating the dead, but the newspapers couldn’t resist sensationalising it. There were even rumours that the boys had made up the avalanche. “Ethically, religiously, there are a lot of things you can write about this,” he says. “But it never bothered me. Never.” He speaks proudly of the fact that the survivors’ foundation, Fundación Viven, played a significant role in getting the Uruguayan population signed up to organ donation.

“We donated our bodies,” he says. “You could die, and you could help the other ones to live. That was a fantastic thing that we did together. I try to explain to people what happened, and that they would have done the same thing. I don’t try to justify anything.”

It took Parrado the best part of a year to recover physically. He ate normally, and slowly reintroduced his rugby training; 10 months later he played in the last few games of the season. He’s coy about how long it took him to recover mentally. How could he possibly know? But he says he suffered no trauma, never felt guilt and never saw a psychiatrist.

“I mean, we survived something that is not survivable. We’re going to teach the psychiatrist things that he doesn’t know.”

To him, his incredible feat is not the defining part of his life. His life after is what matters. He has a wife, Veronique, two daughters and four grandchildren. He’s now on the verge of retiring (“I’m still working but I have the landing gear down on the aeroplane”), bringing to a close a career that has seen him run a successful television production company, grow the family hardware business and, at one stage, race cars.

Does he ever find his thoughts drifting back to his traumatic time in the Andes?

“I don’t think a lot about it,” he says. “One thing that I can tell you is that never, in 51 years, have I had a nightmare about the Andes.” He does think about it when he’s making business decisions. “When I have to take a decision, I say: ‘OK, this decision compared to the ones I took up there, this is a joke!’ I mean, what could happen if I go wrong? Over there every decision meant that if it was wrongly taken, I would die.”

Did the experience change the way he thought about death at all?

“You learn to live with death at a young age,” he says. “I’ve seen my friends dying in front of me. I’ve seen them approaching death without fear … they approached it with bravery,” he says. “But don’t get me wrong. I love life. Every time I breathe, it’s like a miracle. I shouldn’t be here. I shouldn’t be talking to you.”

Every year, on 22 December, Parrado and his “brothers in the mountains” gather to mark the anniversary of their rescue. He describes the date as their common birthday, the year they were reborn. He has never missed it. Last year, they commemorated the 50th anniversary with their partners and children. “We took a photograph of 147 persons who are alive because we came back. So this is a story of life,” he says. “And we celebrate the memory of our friends who didn’t come back or our family who didn’t come back.”

Shortly after the boys were rescued, the Uruguayan and Chilean air forces built a grave at the site – a simple steel cross among some rocks. Parrado’s mother and sister, plus all the others who died, are buried there. Parrado has visited 12 times (“You must think that I’m strange or crazy!”). It’s not an easy trek: two and a half days on horseback followed by a 43-mile hike on dirt roads. Up there, with the safety blanket of satellite phones and guides and food, he’s struck by its awesome scale and beauty.

He’s not a sentimental person and would never have returned were it not for his father. “He had been back, before he died, 18 times in a row – 18! – to put flowers on the grave of his beloved wife and daughter and my friends.” On their first trip, his father brought the teddy Susy slept with every night. “I said: ‘Daddy, why are you doing this every year?’ He said: ‘People go to cemeteries to put flowers on the grave of their dear ones – my cemetery is only very far away.’”

His father died in 2008, aged 92. He left a note instructing Parrado to take his ashes to the crash site. On Parrado’s behalf, a family friend did just that, burying him with his wife and daughter in the shadow of Mount Seler.

“Dad had said: ‘Pharaohs and gladiators and Roman emperors, they had big monuments as graves. We have the whole range of the Andes mountains.”

Parrado returned one last time in 2006, this time with his wife and daughters. They told him: “We want to see the place where we were created, where we were born.” At the site, his friend took a picture of Parrado and his family looking out toward the mountain Parrado scaled. It is the only memento he keeps of the Andes. “You can only see our backs, but the four of us are there and that defines my life. When I left that place to climb, I didn’t have that family. I have it now.”

Emily Foster is a globe-trotting journalist based in the UK. Her articles offer readers a global perspective on international events, exploring complex geopolitical issues and providing a nuanced view of the world’s most pressing challenges.