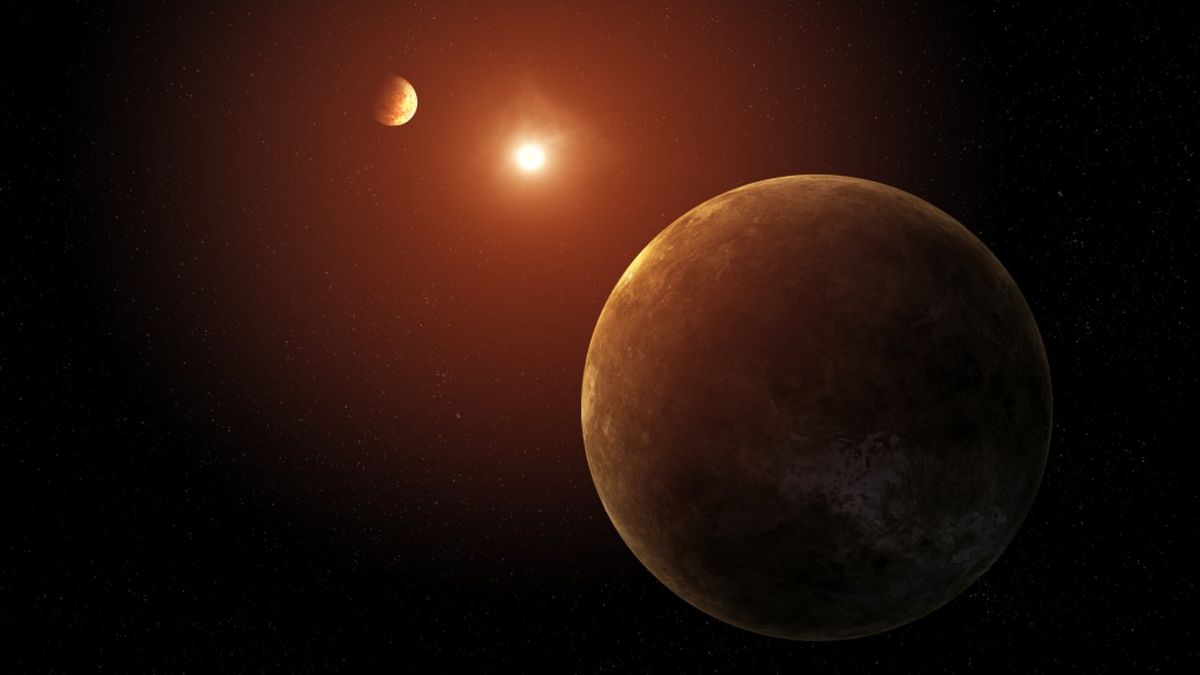

NASA’s Kepler Space Telescope may have saved the best for last. Astronomers combing over data collected by the telescope before its retirement in 2018 have found a system of seven planets being blasted by radiation from their parent star.

Each of the seven blisteringly hot extra-solar planets — or “exoplanets” — in the system Kepler-385 received more radiation from the sun-like star they orbit than any planet in the solar system receives from the sun. The planets all appear to be larger than Earth but smaller than the solar system ice-giant Neptune.

Excitingly, the Kepler-385 system is just one of the highlights in a new Kepler Space Telescope-created catalog of around 4,400 exoplanet candidates and 700 multi-planet systems that has astronomers thrilled about the information they might glean from it.

“We’ve assembled the most accurate list of Kepler planet candidates and their properties to date,” research leader and NASA scientist Jack Lissauer said in a statement. “NASA’s Kepler mission has discovered the majority of known exoplanets, and this new catalog will enable astronomers to learn more about their characteristics.”

Related: Very Large Telescope surprisingly finds exoplanet lurking in 3-body star system

What do we know about the Kepler-385 planets?

The Kepler-385 planetary system, located 4,672 light years away from Earth, is one of the few systems we are aware of that contains more than six planets, with one of the other famous examples being the TRAPPIST-1 system of seven Earth-like planets.

At the heart of Keplar-385 is a star around 1.1 times larger and 5% hotter than our sun. The inner planet, Kepler-385 b, has a mass around 12.8 times greater than Earth’s and is 2.7 times as wide as our planet. It orbits its star at around 10% of the distance between Earth and the sun and completes an orbit in around 10 Earth days.

The next planet out, Keplar-385 c, is slightly larger and has a mass around 13.2 times that of our planet. Its orbit is a perfect circle that covers just around 13% of the distance between Earth and the sun, and it orbits its star in just over 15 Earth days.

Both Keplar-385 c and Keplar-385 b are thought to be rocky planets with thin atmospheres. The remaining five planets are further out and are believed to be roughly twice the size of Earth and are thought to be enshrouded in thick atmospheres.

The Kepler space telescope first started observing the universe in 2009, and its primary mission ended in 2013. After this, the space telescope embarked on an extended mission that lasted until it was decommissioned in 2018.

But as this new research shows, even half a decade after it shut down, data collected by Kepler is still a treasure trove for astronomers revealing more about the Milky Way and its stellar and planetary occupants. (Kepler even once confirmed that our galaxy has more planets than stars, according to NASA.)

Even though the final chapters of the Kepler mission are aimed at measuring how common planets are around other stars, this discovery shows how the latest exoplanet catalog update can allow scientists to determine the characteristics of worlds outside the solar system.

By using improved calculations of stellar characteristics and by better modeling the orbits of exoplanets around them, the new Kepler catalog update can help astronomers identify when a star hosts several planets that cross or “transit” their faces. These planets typically have more circular orbits than when a star hosts only one or two such worlds.

A paper detailing the discovery of the Kepler-385 system and the other new entries in the Kepler catalog is set to be published in The Journal of Planetary Science. A preprint version is available on the paper repository arXiv.

Dr. Thomas Hughes is a UK-based scientist and science communicator who makes complex topics accessible to readers. His articles explore breakthroughs in various scientific disciplines, from space exploration to cutting-edge research.