This week marks the 40th anniversary of the first launch of the European Space Agency’s (ESA’s) Spacelab module aboard astronaut John Young’s final Space Shuttle mission.

Spacelab was a significant step for the Europeans. It was born from studies undertaken by the European Launcher Development Organisation (ELDO) and European Space Research Organisation (ESRO) – the precursors of today’s ESA.

As the Apollo program began to wind down, NASA considered how to get to orbit and do useful work without requiring more expendable Saturn rockets. ELDO proposed a reusable space tug, but NASA opted for a ‘kick-stage’ from its Space Shuttle, which was still on the drawing board.

Astronauts Owen Garriott on the body restraint system and Byron Lichtenberg prepare for a Vestibular Experiment during the Spacelab-1 mission. The experiments looked at the interaction between the organs in the ear, vision, and spinal reflexes in humans (click to enlarge) Pic: NASA / MSFC

However, while the Space Shuttle might have been signed off, the space station that it was going to be used to build was not. The future of ELDO’s space tug was also uncertain, but ESRO was hard at work on a sortie module that would fit into the cargo bay of NASA’s Space Shuttle.

ESRO’s work would become the Spacelab. Its director general from 1971 to 1974 said of the module: “Spacelab was the indispensable element to transform the Shuttle into a first-generation Space Station.”

This is handy, because Space Shuttle delays would doom Skylab, and NASA’s dreams of building another space station of its own seemed forever on the back-burner.

Fast-forward to 40 years ago – November 28, 1983 – and the first Spacelab module was nestled in the payload bay of Space Shuttle Columbia for STS-9. As well as John Young, former Skylab astronaut Owen Garriott was also on board as a Mission Specialist, and ESA astronaut Ulf Merbold was present. Merbold was the first non-US citizen to fly on the Space Shuttle and the first ESA astronaut and West German to go into space.

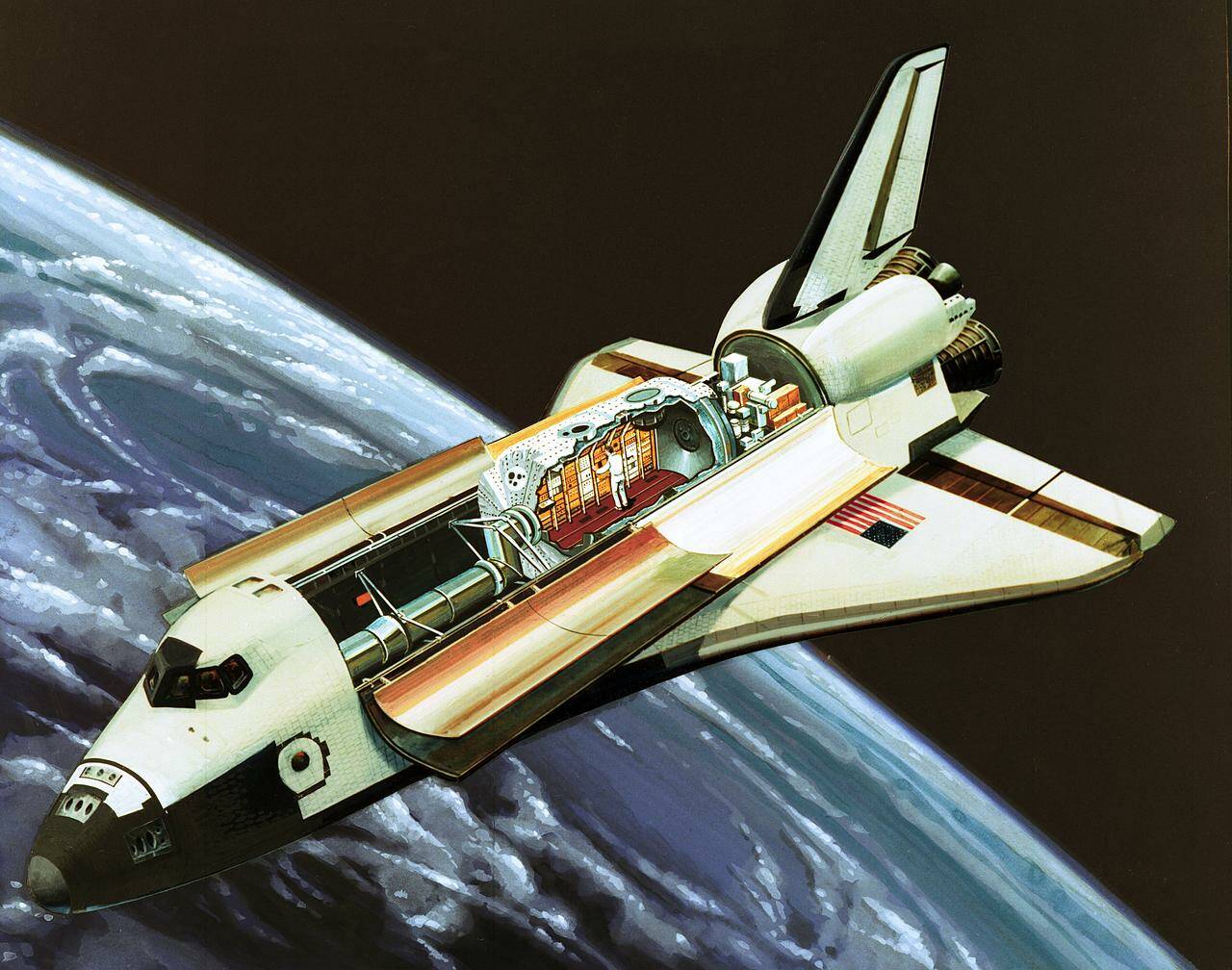

As for the Spacelab itself, it was situated in the rear of the payload bay and connected to the Space Shuttle crew compartment by a tunnel.

The mission was hugely delayed, largely due to problems developing the Space Shuttle. The original launch date – December 1980 – continued to slip and resulted in the payload crew going through five years of training.

Of the preparation, NASA noted in its history: “The entire payload crew spent so much of their time travelling to Europe that John W. Young, who was then chief of the Astronaut Office, called their flight assignment and European training, which involved travel to exotic locations like Rome, Italy, ‘a magnificent boondoggle. In my next life,’ he declared, ‘I’ll be an MS [mission specialist] on S Lab [Spacelab]’.”

That said, having Europeans involved put some US noses out of joint. In NASA’s history, Merbold said: “In Houston you could feel that not everyone was happy that Europe was involved. Some also resented the new concept of the payload specialist ‘astronaut scientist,’ who was not under their control like the pilots. We were perceived to be intruders in an area that was reserved for ‘real’ astronauts.”

Astronaut Owen K. Garriott, STS-9 mission specialist, left, and Ulf Merbold, payload specialist. Dr Garriott holds in his left hand a data/log book for the solar spectrum experiment. Dr Merbold holds a map in his left hand for the monitoring of ground objectives (click to enlarge) Pic: NASA / MSFC

The European astronauts were, for example, not permitted to use the astronaut gym or participate in T-38 flight training. However, as time passed, attitudes changed – something Garriott and Merbold credited to the STS-9 commander, John Young.

NASA again: “As the crew was preparing to fly, the former moonwalker [Young] took Merbold on a T-38 ride, and when the payload specialist asked if he could fly the plane, Young willingly offered him the opportunity. After that flight, Merbold recalled that he ‘enjoyed John Young’s unqualified support’.”

The mission went well and laid the groundwork for further cooperation between the agencies and countries, most notably the International Space Station and ESA contributions to the effort to return humans to the Moon.

In his book Forever Young – written with James R. Hansen – John Young described the mission as “A truly notable flight,” although he also remarked, “Entry of STS-9 turned out to exciting – too exciting.”

Two of Columbia’s flight computers crashed shortly before re-entry. Young noted: “One of which we restored only to have it fail again at landing.”

He went on: “The cause of one of the failures turned out to be a sliver of solder eleven-thousandths of an inch thick that became dislodged when the thrusters were fired, shorting out the CPU board.”

STS-9 had an eventful landing. As well as the computer failures, one of the orbiter’s three auxiliary power units (APUs) caught fire and burned itself out – something that lay undiscovered until days later.

Still, as Young noted: “All in all, Spacelab 1 was highly successful. It proved that complex experiments in space could be carried out using non-NASA personnel who had been trained as payload specialists.”

Two Spacelab laboratory modules – LM1 and LM2 – were built. LM1’s last flight was in 1997 and LM2 last flew in 1998, both aboard Columbia. The program’s legacy continued in projects such as ESA’s ATV freighter and many of the International Space Station (ISS) modules, including the ESA Columbus laboratory. ®

Dr. Thomas Hughes is a UK-based scientist and science communicator who makes complex topics accessible to readers. His articles explore breakthroughs in various scientific disciplines, from space exploration to cutting-edge research.